Great Russian Writers: An Ethnic and Ideological Study

Ethnicity and Ideology in the Pantheon of Great Russian Writers

This is a continuation of my series on Russia. In this rendition I will be looking at Russian writers to paint a general overview of Russian literary genius and it’s composition.

For each writer I will classify their significance, write about their attitudes towards the West and Russian society, their philosophy, ideology, ethnicity, religion, family background, government repression (if took place) and HPI value as provided by Pantheon world and finally a quote from them (I skipped a few people because they had nothing important to say)

This is by no means an overview of Russian philosophy or anything like that for many people who were non-fiction political or scientific writers like Alexander Bogdanov, Georgi Plekhanov, Alexandre Kojeve or Mikhail Bakhtin were excluded. If you wish to have a better overview of Russian philosophy, I recommend starting from Wikipedia.

Furthermore, a lot of modern day Russian writers were also excluded, partially because there weren’t that many but partially because I wanted to end with the fall of the Soviet Union.

There is just one issue with my methodology which may ruin some findings besides me forgetting to add a specific writer. As time progressed, the HPI threshold for entry into my list increased. It was 56 during the Enlightenment period but by the end of the list it was close to 70 which is pretty high (resulting in exclusion of many writers of the late Soviet period like Dovlatov). This is not a consistent methodology, but that is because early Russian writers and thinkers were less known and way less numerous than Russian writers at the dawn of the XXth century and I couldn’t fathom having one or two thinkers of the enlightenment while 20 thinkers between 1890 and 1920.

If you don’t wish to read massive walls of text, you can go straight behind the paywall section that will summarize the findings and provide a statistical analysis of the general findings of this study such as:

The ethnic breakdown of Russian authors (by period)

The political breakdown of Russian authors (by period, and their correlations)

The family origins of the Russian authors.

How based the Russian authors were and what correlation it had with greatness

The levels of repression of the Russian authors (by period and their correlations)

Which Russian groups of authors were repressed the most and by whom.

Russian authors belonging to which political ideology are most elite human capital coded and which ideologies were low human capital coded.

Whether each great writer despised the current order they were living under.

Their attitudes towards the West.

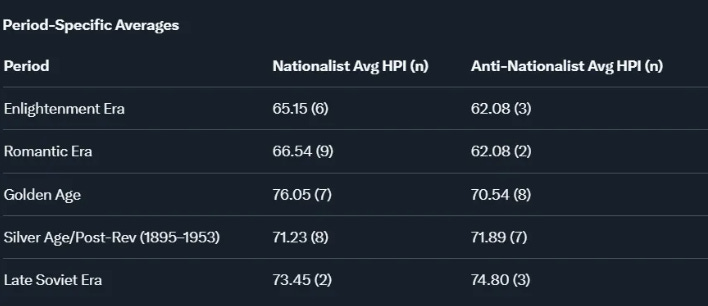

Here is a teaser into the type of data you are about to see behind the paywall:

Enlightenment Era:

Vasily Trediakovsky (1703-1769):

Significance: Early pioneer of Western and French norms into Russian Literary Forms.

Rejoice, all Russian peoples:

With us, the golden years are coming.

HPI value: 57.16

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critical of its backwardness and resistance to reform; sought to elevate it through Western-inspired education and literature, viewing it as in need of enlightenment to match European progress.

Attitudes towards the West: Positive, Francophile

Philosophy: Rationalist, Classicism

Ideology: Westernizer, Supporter of Autocracy

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Eastern Orthodox

Family background: Priest, educated in France.

Government repression: None, worked with the Russian Academy of Science but was bullied by Lomonosov and other Russian academics for lacking native flair.

Antiochus Kantemir (1708-1744):

Significance: “Grand-Grandfather of Russian Poetry”

In others’ hands, crumbs of bread seem like large slices.

HPI value: 61.99

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critical, viewed it as backward

Attitudes towards the West: Positive, as worth emulating

Philosophy: Rationalist, Moralist

Ideology: Westernizer, Supporter of Autocracy

Ethnicity: Moldovan/Romanian, Greek, Tatar

Religion: Eastern Orthodox

Family background: Noble, scientist and royalty background. Family is invited to Russia by Peter the Great

Government repression: None, worked with the government

Alexander Sumarokov (1717-1777)

Significance: “Father of Russian drama”

Morality without politics is useless, politics without morality is dishonorable.

HPI value: 59.41

Attitudes towards Russian society: Deeply ambivalent but hopeful.

Attitudes towards the West: Aspirational and positive. Francophile.

Philosophy: Classicism, Rationalist and Ethical Idealist

Ideology: Westernizer, Reformer, Supporter of Autocracy

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Eastern Russian Orthodox but Secular

Family background: Old Muscovite service gentry

Government repression: Got sidelined by Catherine the Great later on.

Mikhail Lomonosov (1711 - 1765)

Significance: Polymath, primarily a scientist and inventor, but also a writer and an educator. First widely acclaimed Russian writer.

The greatness, power, and wealth of the entire state lie in the preservation and multiplication of the Russian people.

HPI value: 75.69

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critical but highly patriotic

Attitudes towards the West: “Russia must learn from Europe without surrendering its identity"

Philosophy: Rationalism, Moral Idealism

Ideology: Russian Progressive Nationalism

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Eastern Russian Orthodox but Deist

Family background: Son of fisherman, rose to high ranks through merit and talent.

Government repression: none.

Mikhail Kheraskov (1733–1807)

Significance: Earned the title “Russian Homer” for his epic scope and moral vision by contemporaries.

But I will not endure these reproaches in any way;

It seems easier to me to die in torment

Than to behold my life and honor defiled.

HPI value: 56.16

Attitudes towards Russian society: Staunch patriotic, but societal flaws through allegorical characters in his plays and novels

Attitudes towards the West: Sought a synthesis of Western forms with Russian content

Philosophy: Classicism, Rationalism, Moralism

Ideology: Russian Imperialist and Nationalist

Ethnicity: Father was of partial Wallachian descent, mother is fully Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox

Family background: Gentry, educated at Land Gentry Cadet Corps in Saint Petersburg.

Government repression: none

Yakov Knyazhnin (1742-1791)

Significance: Highly respected playwright and poet by contemporaries. Successor to Alexander Sumarokov, first open critic of government in his play Vadim of Novgorod commemorating Vadim the Bold’s 864 revolt against the Rurikid Vikings.

We shall compose, though thunder strike us dead!”

From the sound of their voices, reams of paper tremble,

Ink flows in rivers, pens march forth to our honor.

HPI value: No data. My own estimation around 59-62.

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critical of unchecked governmental and aristocratic power.

Attitudes towards the West: Westernizer, an admirer of Voltaire. He tailored Western influences to celebrate Russian identity, as seen in his patriotic odes and operas, avoiding slavish imitation and aligning Western forms with national pride.

Philosophy: Classicism, Rationalism

Ideology: Russian Progressive Nationalist, proto-Republican, Liberalism

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox, Secular

Family background: Pskovian noble family, studied at the St. Petersburg Cadet Corps

Government repression: His tragedy Vadim of Novgorod (published 1789, performed 1791) was banned posthumously in 1793 after his death, as its portrayal of a Novgorod hero resisting autocratic rule was deemed subversive amid fears of revolutionary ideas following the French Revolution.

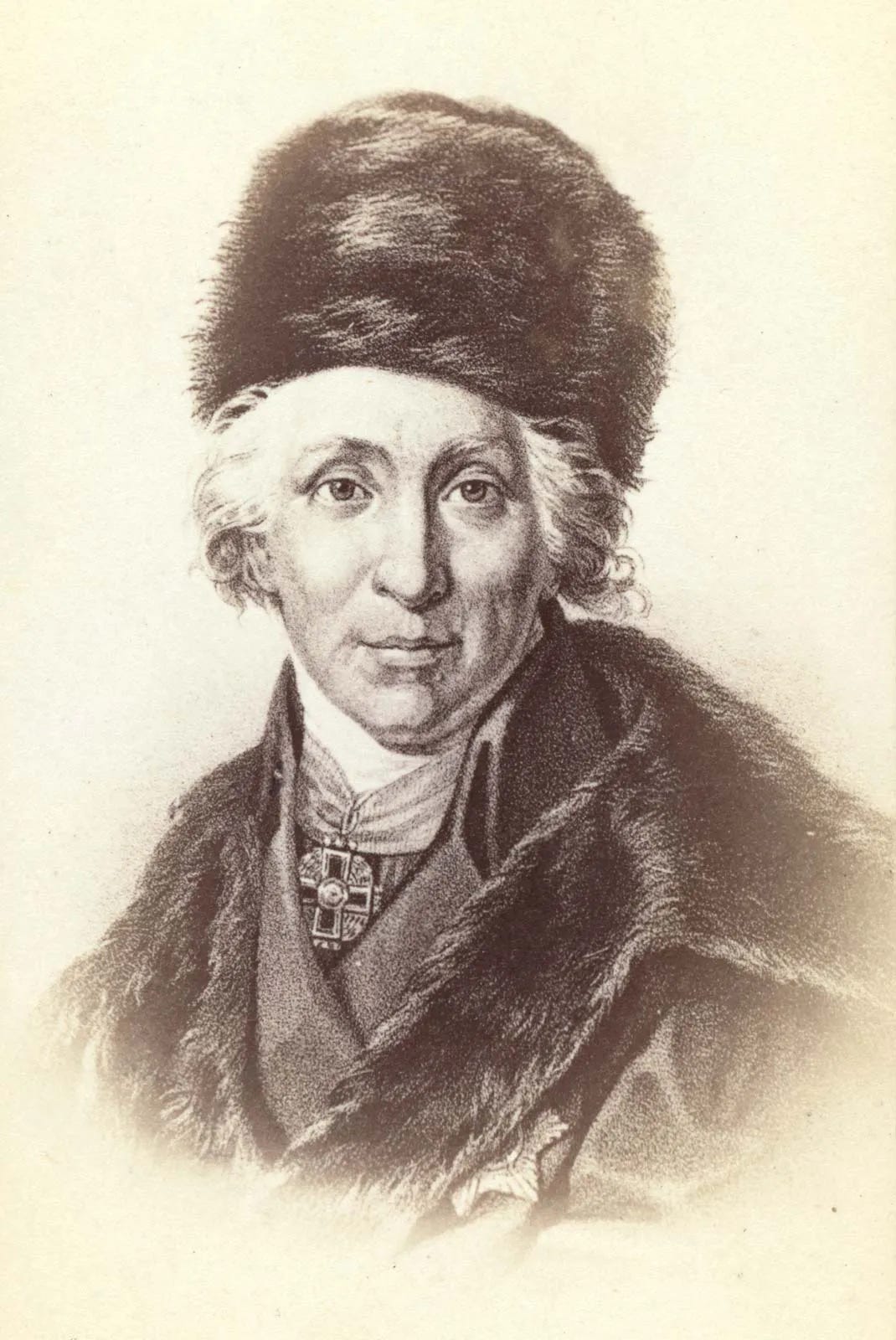

Gavrila Derzhavin (1743-1816)

Significance: “Greatest poet before Alexander Pushkin”

Enemies are our best friends;

They teach us wisdom.

But most of all I fear

Those who torment me with flattery.

HPI value: 66.72

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critical and Patriotic.

Attitudes towards the West: Was influenced by French ideals and grammar. Praised the West but in later years resisted liberal reforms.

Philosophy: Conservative, Moralist

Ideology: Advocate of Absolute Monarchism, Russian Monarchism, Anti-Liberal and Anti-Semitic

Ethnicity: Great Russian, symbolic Tatar roots (below 3%).

Religion: Russian Eastern Orthodox

Family background: Impoverished Russian nobility in Kazan.

Government repression: Worked in the government and had conflicts over exposing corruption and ultimately resigned due to Alexander Ist liberal course, but was never targeted by the government.

Denis Fonvizin (1745-1794)

Significance: Founder of Literary Comedy in Russia. Social commentator. Sharp critic of elite excesses and corruption.

Science and intellect submit to fashion just as much as earrings and buttons.

HPI value: 64.32

Attitudes towards Russian society: Big critic of Russian serfdom and elite corruption.

Attitudes towards the West: In his Letters from France, he mocked French vanity and immorality, favoring Russian moral sincerity despite its flaws. He sought to adapt Western literary forms to Russian contexts, rejecting blind imitation of foreign models and advocating for a distinctly Russian cultural voice rooted in enlightened principles.

Philosophy: Classicism

Ideology: Reformist, Monarchist

Ethnicity: Great Russian, some symbolic Baltic German and Viking ancestry (under 3%)

Religion: Russian Orthodox Christian, Secular

Family background: Russian Rurikid nobility, educated at Moscow University.

Government repression: In 1785, Catherine the Great banned his journal The Companion of Lovers of the Russian Word for its critical tone.

Nikolay Novikov (1744-1818)

Significance: First real Russian journalist. Found multiple independent Russian journals and newspapers.

The prosperity of the state and the well-being of the people depend unreservedly on the goodness of morals, and the goodness of morals depends unreservedly on education.

HPI value: 58.25

Attitudes towards Russian society: Harsh critic of serfdom and governmental corruption, advocated for cultural and moral awakening.

Attitudes towards the West: Admired French and British freethinkers.

Philosophy: Westernizer, Masonic Mysticism

Ideology: Reformist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Freemason.

Family background: Noble family, educated in Moscow University

Government repression: Severe governmental repression over Masonic activities. In 1792, Catherine ordered his arrest, accusing him of spreading dangerous ideas through his publishing and Freemasonry. He was imprisoned in the Shlisselburg Fortress for four years (1792–1796) under harsh conditions, released only after Catherine’s death by Paul I. The ordeal broke his health and finances, forcing him into obscurity until his death in 1818.

Alexander Radishchev (1749-1802)

Significance: The Father of Russian Radicalism. His seminal work, A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow (1790), a scathing critique of serfdom, autocracy, and social injustice. Has Greatly influenced the Decembrist movement and subsequent revolt in 1825.

Autocracy is the most repugnant state to human nature... and the people have the right to judge a despotic monarch.

HPI value: 65.91

Attitudes towards Russian society: He viewed Russia’s social order as backward and oppressive, urging a transformation inspired by Enlightenment ideals to create a more humane and equitable society.

Attitudes towards the West: Committed Westernizer. Deeply influenced by Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Raynal.

Philosophy: Sentimentalist, the conception of Natural Rights.

Ideology: Proto-Revolutionary, anti-serfdom, anti-monarchist

Ethnicity: Great Russian, symbolic Tatar descent (less than 3%)

Religion: Deism. but nominally Russian Orthodox.

Family background: Wealthy noble family. Educated in Moscow and later in Leipzig.

Government repression: After publishing A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1790, Catherine the Great deemed it seditious, accusing him of inciting rebellion. Arrested in June 1790, he was sentenced to death, commuted to ten years’ exile in Siberia (Ilimsk). He endured harsh conditions, returning only in 1797 under Paul I’s amnesty. Under Alexander I, he briefly served on a law reform commission but, disillusioned and possibly pressured, committed suicide in 1802.

The Romantic Era:

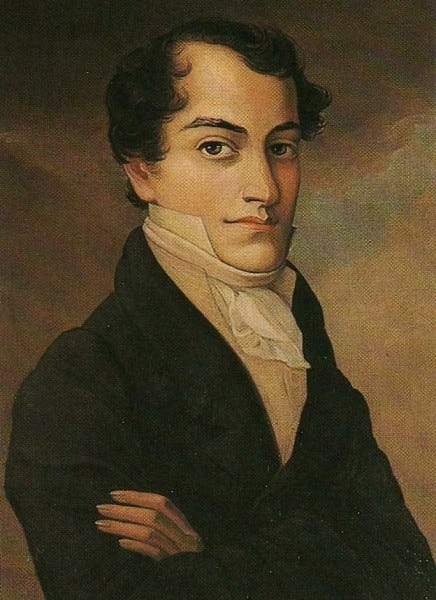

Kondraty Ryleyev (1795-1826)

Significance: Poet, revolutionary, and one of the leading organizers of the Decembrist Revolt of 1825, which sought to overthrow the autocracy and establish constitutional government; his civic poetry and almanac Polar Star promoted liberal ideas and influenced later Russian literature and reform movements.

We are not afraid of death on the battlefield, but we fear to utter a word in favor of justice.

HPI value: 60.61

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critically reformist; viewed Russian society as backward and autocratic, particularly condemning serfdom as a moral evil and the nobility’s complicity in oppression; advocated for social justice, education of the masses, and patriotic sacrifice to uplift the downtrodden, often using his poetry to inspire civic duty over personal gain.

Attitudes towards the West: Admirative and aspirational; his military service in Western Europe (Germany, Switzerland, France) exposed him to liberal constitutionalism and capitalist progress, which he contrasted sharply with Russia’s feudal stagnation, fueling his calls for modernization and Enlightenment-inspired reforms. Was influenced by Rousseau.

Philosophy: Romantic, Civic-Sentimentalist, Westernizer, Republican

Ideology: Revolutionary, Liberal-Republican, Cossack Jingoism

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Deism

Family background: Russian nobility.

Government repression: Hanged along with 4 other leading Decembrists for his role in the failed uprising.

Pyotr Vyazemsky (1792-1878)

Significance: A pioneer of Romanticism, close associate of Alexander Pushkin, and contributor to the literary almanac Polar Star; his witty, conversational poetry and essays shaped Russian literary criticism and liberal thought, while his later diplomatic career and memoirs provided historical insights into 19th-century Russia.

The English say: time is money. The Russians said: life is a kopeck.

HPI value: 57.37

Attitudes towards Russian society: Vyazemsky initially viewed Russian society as culturally backward and overly autocratic, advocating for reform and intellectual freedom in his early liberal phase alongside the Decembrists and Pushkin. He criticized serfdom and bureaucratic stagnation but grew more conservative after the 1825 Decembrist Revolt.

Attitudes towards the West: Highly admiring and cosmopolitan; influenced by his travels in Western Europe (e.g., France, Germany, Italy), Vyazemsky saw the West, particularly French literature and Enlightenment ideals as a model for cultural and intellectual progress.

Philosophy: Romantic individualism, Rationalism

Ideology: Liberalism, Westernizer, Anti-Slavophile, Moderate-Conservatism later in life

Ethnicity: Half-Russian (of Rurikid stock), Half-Irish

Religion: Russian Orthodox, Secular

Family background: Aristocratic; born into the prominent Vyazemsky noble family in Moscow, son of Prince Andrey Vyazemsky and an Irish noblewoman, Jenny Quinn O’Reilly; inherited wealth and status, educated at home by French tutors.

Government repression: Barely any. Worked in the government.

Alexander Bestuzhev (1797-1837)

Significance: Russian Romantic writer, poet, literary critic, and Decembrist revolutionary; co-editor of the influential almanac Polar Star (1823–1825) with Kondraty Ryleyev, which promoted liberal ideas and featured works by Pushkin and other contemporaries; his florid prose tales of the Caucasus (written under the pseudonym Marlinsky) popularized Byronic heroism and exoticism, influencing Lermontov and Dumas, while his participation in the 1825 revolt marked him as a symbol of civic sacrifice and military valor in exile.

The beginning of Emperor Alexander’s reign was marked by the most brilliant hopes for Russia’s prosperity. The nobility rested, the merchants did not complain about credit, the troops served without hardship, scholars studied what they wished; everyone said what they thought, and everyone hoped for even better things amid much that was already good. Unfortunately, circumstances did not allow it, and the hopes grew old without fulfillment. The unsuccessful war of 1807 and other costly events disrupted the finances; but this was not yet noticed in the preparations for the Patriotic War. Finally, Napoleon invaded Russia, and it was then that the Russian people first felt their strength; then a feeling of independence awakened in all hearts—first political, and later national. This was the beginning of free thought in Russia. The government itself uttered the words: “freedom, liberation!” It itself disseminated writings about the abuses of Napoleon’s unlimited power, and the cry of the Russian monarch echoed along the banks of the Rhine and the Seine. The war was still ongoing when the warriors, returning home, were the first to spread discontent among the common people. “We shed blood,” they said, “and now they force us to sweat under corvée again. We saved the fatherland from a tyrant, yet the lords tyrannize us once more.” The troops, from generals to soldiers, upon returning, talked of nothing but “how good it is in foreign lands.” Comparison with their own naturally led to the question: why not the same here?

At first, while people spoke of this freely, it dissipated into the wind, for the mind, like gunpowder, is dangerous only when compressed. The ray of hope that the emperor would grant a constitution, as he had mentioned at the opening of the Sejm in Warsaw, and the attempts by some generals to free their serfs still flattered many. But from 1817 everything changed. People who saw the bad or desired better were forced by the multitude of spies to converse secretly—and thus began the secret societies. The oppression of deserving officers by their superiors inflamed minds. The preference for German names over Russian offended national pride. It was then that the military began to say: “Did we liberate Europe only to impose its chains on ourselves? Did we give a constitution to France only to dare not speak of it, and buy with blood primacy among nations only to be humiliated at home?” The abolition of normal schools and the persecution of education forced people, in hopelessness, to think of more drastic measures. And since the people’s grumbling, arising from exhaustion and the abuses of local and civil authorities, threatened a bloody revolution, the societies resolved to avert a greater evil with a lesser one and to begin their actions at the first convenient opportunity.

Letter to Nicholas I, justifying his actions in the 1825 revolt.

HPI value: 59.52

Attitudes towards Russian society: Critically reformist and anti-autocratic; viewed imperial Russia as despotic and stagnant, condemning serfdom, feudal oppression, and the disconnect between the elite and the people.

Attitudes towards the West: Admirative and integrative; heavily influenced by Western Romanticism (Byron, Hugo, Scott), he advocated adapting European literary forms and Enlightenment ideals of freedom to Russian contexts, seeing the West as a source of inspiration for national progress.

Philosophy: Byronic Romanticism fused with civic humanism.

Ideology: Liberal constitutionalism with Decembrist republican leanings. Russian Imperialist. Russian Progressive Nationalist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox

Family background: Born into the ethnic Russian nobility of Novgorod descent. Fifth son of Alexander Fedoseyevich Bestuzhev, a prominent writer, government councilor, and translator

Government repression: Arrested after the Decembrist Revolt; demoted from officer to private, stripped of rights, imprisoned for 18 months in the Peter and Paul Fortress; exiled to Yakutia (1827), then transferred as a common soldier to the Caucasus front (1829) for redemption through service.

Aleksey Koltsov (1809-1842)

Significance: Prominent Russian poet of the Romantic Era focusing on Peasant and Folk themes. He bridged Romantic individualism with emerging realist tendencies.

Peace is the mystery of God,

God is the mystery of life;

All of nature -

Is in the human soul.

HPI value: 56.9

Attitudes towards Russian society: Held a bittersweet view of Russian society, romanticizing the simplicity and spiritual depth of peasant life while subtly critiquing the hardships imposed by serfdom and urban alienation

Attitudes towards the West: Zero Western influence. Prioritized Slavic authenticity. Some Oriental Persian motifs.

Philosophy: Stoicism, Orthodox Mysticism, Romanticism, Slavophile.

Ideology: Conservative, Proto-Slavophile

Ethnicity: Great Russian.

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox. Works like “To the Almighty” express devout humility and divine providence, blending folk spirituality with Romantic ecstasy

Family background: Wealthy merchant background. Worked as a clerk before dedicating himself to literature.

Government repression: None.

Nikolay Karamzin (1766-1826)

Significance: The “Father of Russian sentimentalism”. But most widely known for his first systematic study of Russian history.

The beginning of Russian history presents us with an astonishing case: the Slavs voluntarily destroy their ancient government and demand rulers from the Varangians, who were their enemies.

HPI value: 69.37

Attitudes towards Russian society: Defended Autocracy and Orthodoxy, glorified Russian Imperial legacy but was not blind to structural inequalities.

Attitudes towards the West: Westernizer though he grew wary of Western revolutionary ideals, particularly after the French Revolution, advocating a selective adoption of Western culture to strengthen Russian identity without undermining autocracy, aligning with a moderated Westernizing vision.

Philosophy: He fused Enlightenment rationalism with sentimentalist emotionalism.

Ideology: Conservative Russian Nationalist and Imperialist. Defender of Russian Autocracy and Serfdom.

Ethnicity: Great Russian, symbolic Tatar ancestry (less than 1%)

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox

Family background: Born to a noble family from Simbirsk. Educated in Moscow.

Government repression: Enjoyed great patronage.

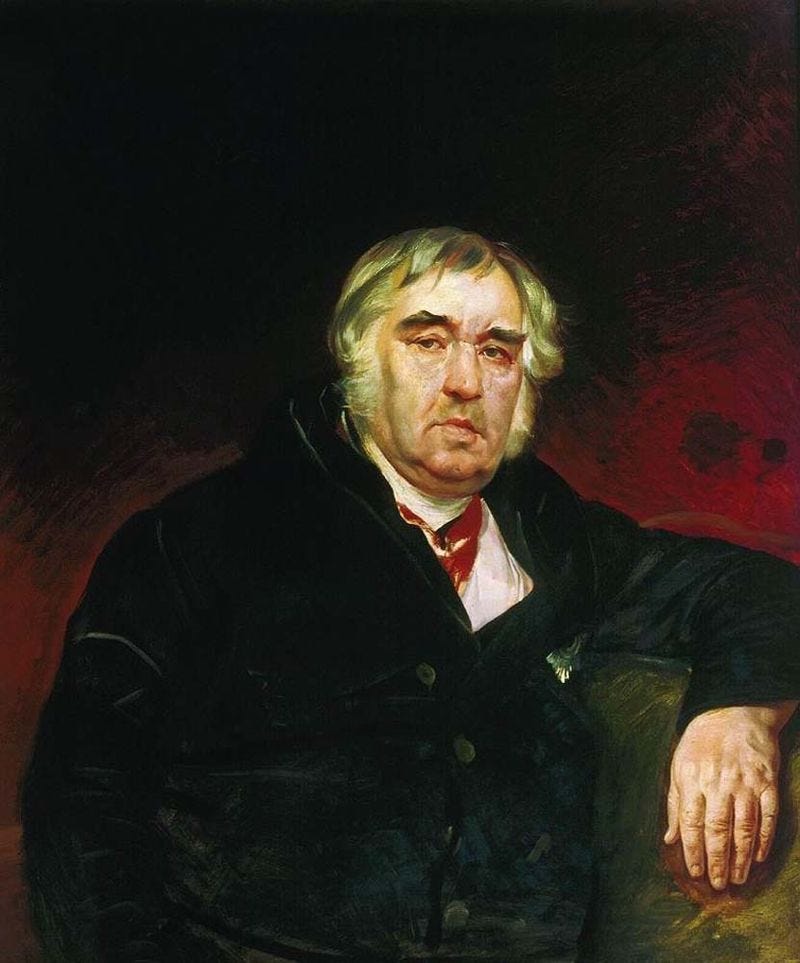

Ivan Krylov (1769-1844)

Significance: A celebrated fabulist and satirist. Often called the “Russian La Fontaine”. Influenced Gogol and Dostoevsky.

To be strong is good, to be smart is twice as good.

HPI value: 71.86

Attitudes towards Russian society: His patriotism shone in fables praising Russian resilience, especially during the Napoleonic Wars, but he remained skeptical of societal progress, emphasizing timeless human flaws over systemic overhaul, aligning with a conservative yet critical view of Russia’s social order.

Attitudes towards the West: Initially a Westernizer. Then cautious of Western influence after the French Revolution and the subsequent invasion of Russia by Napoleon.

Philosophy: Classicism. Moral Pragmatism and Rationalism.

Ideology: Conservative Russian Nationalist. Devout Monarchist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox. His fables drew heavily on Christian ethics.

Family background: Noble family. Self-taught.

Government repression: His early satirical journals, like The Spectator and St. Petersburg Mercury (1793), were briefly suppressed by Catherine the Great for their biting tone, but he avoided serious punishment by moderating his critique. His ability to critique society indirectly through allegory allowed him to navigate censorship while maintaining influence.

Vasily Zhukovsky (1783-1852)

Significance: Foundational figure in Russian Romanticism, often called the “father of Russian poetry”. His advocacy for serf emancipation and moral tone in poetry made him a cultural bridge between Enlightenment and Romanticism, revered for his gentle humanism.

For a society raised on the word of the Gospel, it is perfectly clear and undoubted that the killing of a person, even if committed by the sword of the state, is contrary to the teaching and the reason of Christ’s teaching.

HPI value: 68.23

Attitudes towards Russian society: His poetry celebrated Russian folklore and spirituality, idealizing rural life and Orthodox values, as seen in “Svetlana.” However, he privately criticized serfdom and autocratic rigidity, advocating gradual reform through education and moral enlightenment. As tutor to Alexander II, he instilled liberal ideas, contributing to the eventual abolition of serfdom in 1861. While loyal to the monarchy, he deplored societal stagnation and aristocratic superficiality, using poetry to promote moral and cultural progress within the autocratic framework.

Attitudes towards the West: Zhukovsky was a prominent Westernizer, deeply influenced by European Romanticism, particularly German poets like Schiller and Goethe, and English writers like Byron and Scott. His translations and ballads introduced Western Romantic themes—individualism, nature, and the supernatural—to Russia, enriching its literary tradition. His travels in Europe (1815–1817) reinforced his admiration for Western culture, but he adapted these influences to celebrate Russian identity, avoiding blind imitation

Philosophy: Quintessentially Romantic. German Idealism, Orthodox Mysticism.

Ideology: Liberal Monarchism. Gradual Reformism.

Ethnicity: A son of a Russian landowner and his Turkish slave. 50% Russian 50% Turkish.

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox.

Family background: Russian landowner from Tula. Educated in Moscow.

Government repression: none.

Alexander Griboyedov (1795-1829)

Significance: Russian poet, playwright and diplomat best known for his verse comedy Woe from Wit (1823), a masterpiece of Russian literature that satirized the hypocrisy and conservatism of Moscow’s aristocracy. The play, blending neoclassicism with emerging realism, influenced Russian drama and literature, impacting figures like Pushkin and Gogol.

There is no nation that conquers so easily and knows so poorly how to make use of its conquests as the Russians.

HPI value: 66.75

Attitudes towards Russian society: Griboyedov was a sharp critic of Russian society, particularly the superficiality and intellectual stagnation of the nobility.

Attitudes towards the West: He admired Western intellectual freedom and cultural sophistication, critiquing Russia’s slavish imitation of French fashions in his play. However, his diplomatic service in Persia and the Caucasus deepened his appreciation for Russia’s distinct identity, leading him to advocate a selective adoption of Western ideas to modernize Russia without losing its national character.

Philosophy: Romantic Individualism. Secular Humanism.

Ideology: Russian Progressive Nationalist and Imperialist. Liberal Reformer.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox, Secular.

Family background: Comes a prominent Russian noble family. Studied at Moscow University.

Government repression: The play Woe from Wit was censored under Nicholas I, with performances banned until 1831, as its satire of the elite and subtle liberal undertones raised suspicions, especially after the Decembrist Revolt (1825). Griboyedov was briefly arrested in 1826 for alleged ties to the Decembrists, given his acquaintance with some conspirators, but was released due to lack of evidence.

Yevgeny Baratynsky (1800-1844)

Significance: Romantic poet. Regarded as an anti-thesis to Alexander Pushkin in style.

I congratulate you on the future, for we have more of it than anywhere else; I congratulate you on our steppes, for they are a vastness that cannot be replaced by the local science; I congratulate you on our winter, for it is more invigorating and brilliant, and with the eloquence of frost calls for movement better than the local orators; I congratulate you on the fact that we are indeed twelve days younger than other nations and therefore may outlive them, perhaps, by twelve centuries.

(On Europe)

HPI value: 60.69

Attitudes towards Russian society: His poetry often critiqued the emptiness of aristocratic life and the cultural decline he perceived in the post-Napoleonic era, as seen in “The Last Poet,” which laments the triumph of materialism over art. While not a radical, he expressed alienation from both the autocratic elite and emerging commercialism, favoring spiritual and artistic values. His patriotism was subdued, focusing on universal human struggles rather than national glorification, reflecting a Romantic preference for individual introspection over societal engagement.

Attitudes towards the West: He was influenced by European Romanticism, particularly Byron, Shelley, and Goethe. His early exposure to Western literature at the Corps of Pages shaped his lyrical style, and his travels to Finland and Italy deepened his appreciation for European culture. However, he was skeptical of Western materialism and rationalism, critiquing their encroachment on poetic and spiritual ideals in poems like “The Last Poet.” He adapted Western Romantic forms to explore Russian themes, balancing admiration for European artistry with a commitment to a distinct Russian poetic voice, avoiding the radical Westernization of figures like Radishchev.

Philosophy: German-Idealism. Proto-Existentialism.

Ideology: Apolitical, Romantic Individualism.

Ethnicity: Great Russian, Polish ancestry of 12.5%.

Religion: Russian Orthodox

Family background: His paternal line comes from a Polish noble family that has migrated into Russia in late 17th century. His father was a general. Evgeny was educated in Saint Petersburg.

Government repression: none.

Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837)

Significance: Is universally believed to be the Greatest Russian poet of all time and the founder of modern Russian literature. His works, including the verse novel Eugene Onegin (1825–1832), the narrative poem The Bronze Horseman (1833), the drama Boris Godunov (1825), and short stories like The Queen of Spades (1834), blended Romanticism with realism, establishing a distinctly Russian literary voice. Pushkin’s mastery of language, psychological depth, and exploration of themes like freedom, love, and fate influenced virtually every subsequent Russian writer, from Dostoevsky to Tolstoy.

Of course, I despise my homeland from head to toe—but I am vexed when a foreigner shares this feeling with me.

I swear on my honor that for nothing in the world would I want to change my homeland or have any other history than that of our ancestors, such as God gave it to us.

HPI value: 84.64

Attitudes towards Russian society: Pushkin was a critical yet affectionate observer of Russian society. His poetry and prose captured the complexities of Russian life its beauty, contradictions, and injustices reflecting both pride in its heritage and frustration with its stagnation.

Attitudes towards the West: Was deeply influenced by Shakespeare, Byron, Schiller, Goethe and Voltaire and liked Western culture. Nonetheless he rejected its imitation, mocking Gallicized nobles in Eugene Onegin and celebrating Russia’s unique spirit. He sought to synthesize Western forms—such as the novel in verse—with Russian themes, creating a national literature that rivaled European models while preserving Slavic identity, balancing admiration for the West with patriotic pride.

Philosophy: Romanticism, Existentialism.

Ideology: Initially sympathetic to the Decembrists. Then a supporter of Enlightened Autocracy. Russian Progressive Nationalist and Imperialist.

Ethnicity: 75% Great Russian 12.5% Swedish and German, 12.5% African

Religion: Russian Orthodox.

Family background: Wealthy Russian noble family. His great grandfather was an African general in the Russian army.

Government repression: His early poems, like “Ode to Liberty” and “The Dagger” (1821), led to his exile to southern Russia (1820–1824) under Alexander I for their anti-autocratic tone. After the Decembrist Revolt, Nicholas I personally oversaw his surveillance, censoring his works and restricting his travel.

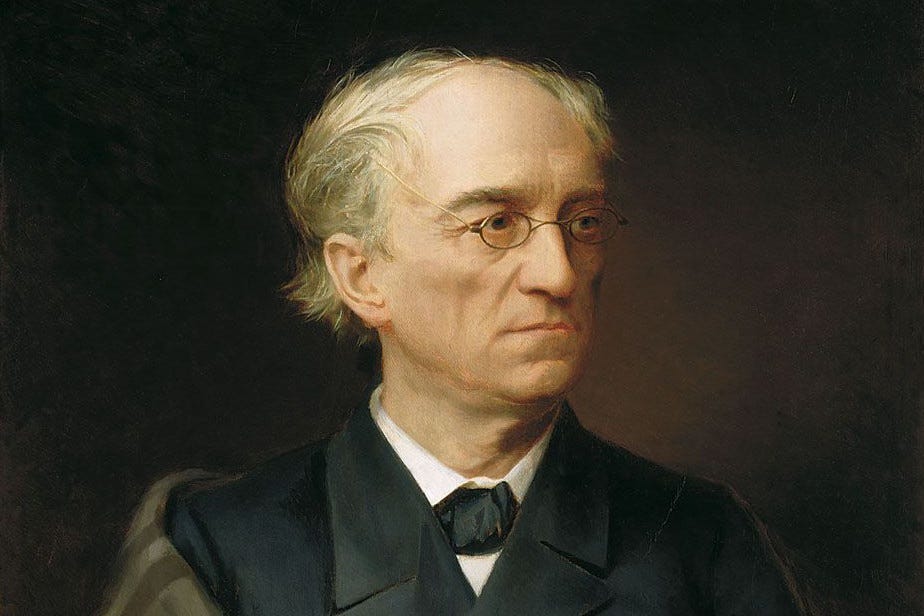

Fyodor Tyutchev (1803-1873)

Significance: Was a classic Russian Romantic poet leaving a lasting impact on Russian literature and political thought.

You cannot grasp Russia with the mind,

Nor measure her with common yardstick:

She has a special stature —

In Russia one can only believe.

HPI value: 68.05

Attitudes towards Russian society: Tyutchev viewed Russian society with a mix of reverence and critique. His political writings praised Russia’s spiritual mission as the heart of Slavic unity. He criticized the Russian elite’s superficial Westernization, advocating a return to Orthodox values and national authenticity.

Attitudes towards the West: He saw Russia’s autocratic system as a bulwark against Western liberalism

Philosophy: Romanticism, Idealism, Slavophile

Ideology: Pan-Slavism. Conservative Russian Nationalism and Imperialism. Reactionary. Fully supported Czar Nicholas I.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox

Family background: Noble background. Studied in Moscow University.

Government repression: none, worked for the government and even became a censor himself.

Aleksey Khomyakov (1804-1860)

Significance: A philosopher, theologian, poet, and co-founder of the Slavophile movement. His essays, such as On the Old and the New (1839) and The Church is One (1844–45), articulated a vision of Russian cultural and spiritual superiority rooted in Orthodoxy and communal traditions (sobornost). As a leading intellectual, he influenced Russian religious philosophy, shaping thinkers like Solovyov and Dostoevsky, and his ideas on Russia’s unique path resonated in later nationalist and Orthodox thought, despite limited recognition during his lifetime.

There is nothing sedimentary or crystalline in the Russian language; everything excites, breathes, lives.

HPI value: 62.67

Attitudes towards Russian society: Khomyakov idealized Russian society’s pre-Petrine traditions, particularly its communal peasant structures (mir) and Orthodox spirituality, viewing them as morally superior and organic. He criticized post-Petrine Russia for adopting Western rationalism and autocratic centralization, which he saw as alienating and corrosive to Russia’s spiritual unity. He advocated a return to communal, faith-based values to restore Russia’s authentic identity.

Attitudes towards the West: Highly critical; Khomyakov viewed Western Europe as spiritually barren, overly individualistic, and dominated by rationalism, Catholicism, or Protestantism, which he considered inferior to Orthodoxy’s holistic unity. He saw Western legalism and materialism as fragmenting society, contrasting this with Russia’s communal and spiritual harmony, though he engaged with Western philosophy to critique it.

Philosophy: Sobornost, Idealism.

Ideology: Slavophile. Conservatism.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox.

Family background: Born into a wealthy, aristocratic Russian family; son of Stepan Alexandrovich Khomyakov, a nobleman, and Maria Alekseevna (née Kireevskaya), from a cultured gentry family. Raised in Moscow and their Oryol estate, he received a privileged education, studying mathematics, literature, and philosophy, and served briefly in the military before dedicating himself to intellectual pursuits.

Government repression: Minimal; Khomyakov faced censorship under Nicholas I’s regime for his Slavophile writings, which indirectly challenged tsarist Westernization and autocracy.

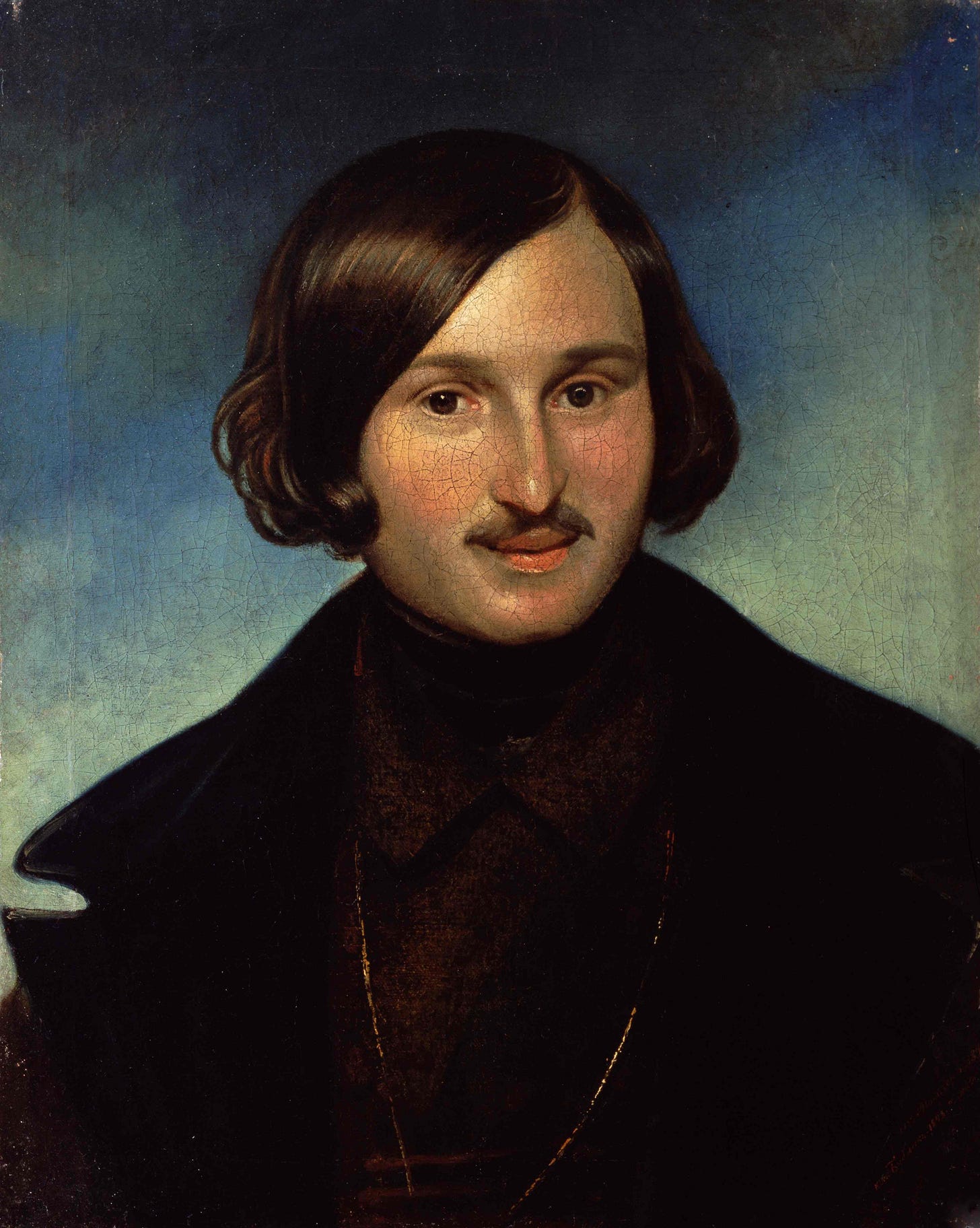

Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852)

Significance: Towering figure in Russian and worldly literature. His social commentary and patriotic works like Dead Souls and Taras Bulba are part of a Russian school curriculum. He blended Realism with Romanticism and folklore. Influenced writers like Dostoevsky and Chekhov.

If only one farmstead remains to the Russians, even then Russia will be reborn.

HPI value: 82.82

Attitudes towards Russian society: Complex. Some of his works critiqued bureaucratic corruption, materialism, and greed. At the same time was highly patriotic of Russia and its order as well as of Ukrainian folklore.

Attitudes towards the West: Critical of Western materialism and secularism, especially after his spiritual crisis, viewing Russia’s Orthodox spirituality as superior. He admired Western literary techniques but rejected liberal ideologies, favoring a uniquely Russian path of moral redemption over Western modernization, aligning more with Slavophile ideals in his later years.

Philosophy: Slavophile, Religious Mysticism, Asceticism, Russian Exceptionalism.

Ideology: Conservative Russian Nationalist and Imperialist, Defender of Russian Autocracy and Serfdom, Cossack Jingoism.

Ethnicity: Little Russian (Ukrainian). Possible 1/8 Polish ancestry.

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox

Family background: Minor noble.

Government repression: None.

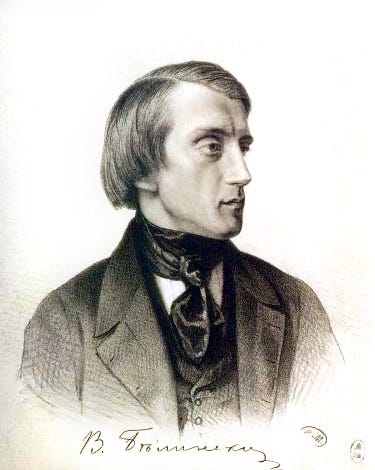

Vissarion Belinsky (1811-1848)

Significance: A leading Russian critic, philosopher, and publicist of the early half of the century. He played a central role in shaping the Westernizer faction of the Russian intelligentsia. His passionate essays influenced generations of writers (including Pushkin, Gogol, Lermontov, Turgenev, and Dostoevsky) and intellectuals, emphasizing literature’s role in social reform, individual dignity, and national progress. He is often called the “father of the Russian intelligentsia” for bridging Romanticism and realism in art, and his ideas laid groundwork for later revolutionary democratic thought. of the early half of the century

“I am of Russian nature. Let me say it more clearly: je suis un Russe et je suis fier de l’être. I don’t even want to be French, although I love and respect that nation more than others. The Russian personality is still an embryo, but how much breadth and strength there is in the nature of this embryo, how stifling and terrifying any limitation and narrowness is to it.”

HPI value: 70.82

Attitudes towards Russian society: Highly critical of autocracy, serfdom, censorship, and spiritual stagnation under Nicholas I; viewed Russian society as backward and in need of radical reform to awaken human dignity and progress toward civilization. He condemned the oppression of the peasantry and intelligentsia, seeing literature as a tool for social awakening amid repression.

Attitudes towards the West: Admirative and Europhilic; advocated Westernization as the path for Russia’s maturation, praising European literature, philosophy, politics, and values (e.g., individualism and rationalism) as models for Russian cultural and social development.

Philosophy: Westernizer, Hegelian, Romantic Realism, Materialism.

Ideology: Democratic, Anti-Autocracy

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Atheist.

Family background: Son of Grigory Ivanovich Belinsky, a low-ranking Russian naval physician and district doctor, and Maria Ivanovna (née Popova), daughter of a Russian sailor.

Government repression: expelled from Moscow University in 1832 for a play criticizing serfdom; lost editorial positions (e.g., at Moscow Observer in 1839) due to association with banned works like Chaadaev’s Philosophical Letters; his 1847 open Letter to Gogol (denouncing serfdom and Orthodoxy) was deemed subversive, circulated underground, and contributed to the 1849 Petrashevsky Circle arrests (including Dostoevsky).

Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841)

Significance: Towering figure in Russian Romanticism, often considered second only to Pushkin. He blending psychological depth, existential despair, and vivid imagery. Lermontov’s works critiqued societal hypocrisy and explored themes of alienation, fate, and rebellion, influencing later writers like Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

The Russian people, this hundred-armed giant, will sooner endure the cruelty and arrogance of their ruler than his weakness.

HPI value: 74.97

Attitudes towards Russian society: He was critical of Russian government. His patriotism was tinged with disillusionment, critiquing Russia’s spiritual and intellectual stagnation while cherishing its landscapes and folk traditions.

Attitudes towards the West: He was heavily influenced by European Romanticism, particularly Byron, Schiller, and Shelley. His Byronic heroes and lyrical style reflect Western Romantic ideals of individualism and rebellion. However, he was skeptical of Western materialism and aristocratic affectations, mocking Russified European manners in his works.

Philosophy: Individual Romanticism, German Idealism, Existentialism, Fatalism.

Ideology: Liberal

Ethnicity: Great Russian. Symbolic Scottish ancestry (below 6%)

Religion: Russian Orthodox

Family background: Wealthy noblemen, educated in Moscow University and School of Guards Sub-ensigns subsequently entering military service.

Government repression: His poem “Death of the Poet” (1837), blaming the court for Pushkin’s death, led to his arrest and exile to the Caucasus as a military officer. A second exile followed in 1840 after a duel with a French diplomat’s son.

The Golden Age of Russian Literature:

Alexander Herzen (1812-1870)

Significance: A prominent Russian philosopher, writer, and revolutionary thinker, often called the “father of Russian socialism.” As an émigré in London, he published The Bell, which smuggled ideas into Russia, influencing the intelligentsia and reformist movements. His blend of socialism, liberalism, and Russian populism left a lasting impact on revolutionary ideology.

The state has settled in Russia like an occupying army. We do not feel the state as part of ourselves, part of society. The state and society are waging war. The state is waging a punitive one, and society a guerrilla one…A people cannot be liberated more than it is free from within… Socialism will develop in all its phases to its extreme consequences, to absurdities. Then once again a cry of negation will burst from the titanic breast of the revolutionary minority, and once again a mortal struggle will begin, in which socialism will take the place of the current conservatism and will be defeated by the coming revolution, unknown to us.

HPI value: 71.88

Attitudes towards Russian society: Herzen was a fierce critic of Russian autocracy, serfdom, and bureaucratic corruption, viewing them as oppressive and morally bankrupt. He idealized the Russian peasantry, particularly their communal landholding system (the obshchina), as a foundation for a uniquely Russian form of socialism. His works mourned the alienation of the nobility from the masses and condemned the tsarist regime’s stagnation.

Attitudes towards the West: Initially a Westernizer but after the failed 1848 revolutions, he grew disillusioned with Western liberalism and capitalism, criticizing their individualism and inequality. He believed Russia could bypass Western-style capitalism, developing a socialist system rooted in its communal traditions, blending Western ideas with Russian distinctiveness. Supported the West and the Ottoman Empire in the Crimean War.

Philosophy: Socialist Idealism. Hegelian.

Ideology: Peasant Socialism. Anti-Russian Imperialist.

Ethnicity: Russian Father. German mother.

Religion: Agnostic. Saw religion as tools of oppression.

Family background: Born in Moscow, Herzen was the illegitimate son of Ivan Yakovlev, a wealthy Russian noble, and Henriette Haag, a German woman. Studied in Moscow University.

Government repression: His early radical activities, including involvement in socialist discussion circles, led to his arrest in 1834 and exile to Vyatka and Vladimir (1835–1840) under Nicholas I. After inheriting wealth, he emigrated to Europe in 1847, escaping further persecution.

Ivan Goncharov (1812-1891)

Significance: Major Russian realist writer and social critic.

Russia is a country that strives for freedom but always remains a slave.

HPI value: 72.53

Attitudes towards Russian society: Goncharov was critical of the inertia and backwardness of Russian society, particularly the landed gentry, as depicted in Oblomov. He also distrusted radical reforms and revolutionary zeal, favoring gradual modernization while preserving cultural roots.

Attitudes towards the West: Balanced. He admired Western technological and organizational advancements (e.g., British colonial efficiency) but criticized their materialism and cultural arrogance. He saw Russia as distinct, valuing its spiritual and communal traditions over Western individualism, yet he advocated for adopting Western discipline and work ethic to modernize Russia

Philosophy: Realism. Naturalism.

Ideology: Conservative Reformism.

Ethnicity: Great Russian.

Religion: Russian Orthodox Christian

Family background: Born into a wealthy merchant family in Simbirsk. Educated in Moscow.

Government repression: None. Worked as government official at some point.

Aleksey Tolstoy (1817-1875)

Significance: Russian Romantic poet, novelist, playwright, and translator; a key figure in the Golden Age of Russian literature, known for his lyrical poetry, historical dramas (e.g., The Death of Ivan the Terrible, 1866), and the novel Prince Serebryany (1862), which romanticized Russia’s past; co-creator of the satirical pseudonym Kozma Prutkov, critiquing bureaucratic absurdity; his works bridged Romanticism and realism, influencing Russian historical fiction and satire.

Complete and naked truth is the subject of science, not art.

HPI value: 67.62

Attitudes towards Russian society: Ambivalent and critical; Tolstoy idealized Russia’s pre-Petrine past and aristocratic honor but criticized contemporary autocratic bureaucracy, serfdom, and moral decay in the nobility; his satirical Kozma Prutkov works mocked officialdom’s incompetence, while his historical dramas and Prince Serebryany portrayed a noble, chivalric Russia corrupted by modern autocracy and Westernization.

Attitudes towards the West: Complex and critical; admired Western Romantic literature (Byron, Schiller) and translated Goethe and Heine, but rejected Western materialism, utilitarianism, and revolutionary radicalism; favored Russia’s spiritual and cultural traditions over Western rationalism, aligning with moderate Slavophile ideals while remaining cosmopolitan in his literary tastes.

Philosophy: Romantic Idealism, Religious Mysticism

Ideology: Aristocratic Liberalism, Moderate Slavophilism

Ethnicity: 50% Great Russian, one quarter Little Russian (Ukrainian) on his mother’s side and is 1/8 French and 1/8 German on his father’s side.

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox

Family background: Born into prominent Tolstoy noble family. His mother is the daughter of Count Alexei Razumovsky.

Government repression: None. Maintained favor with the court, tutored Alexander II.

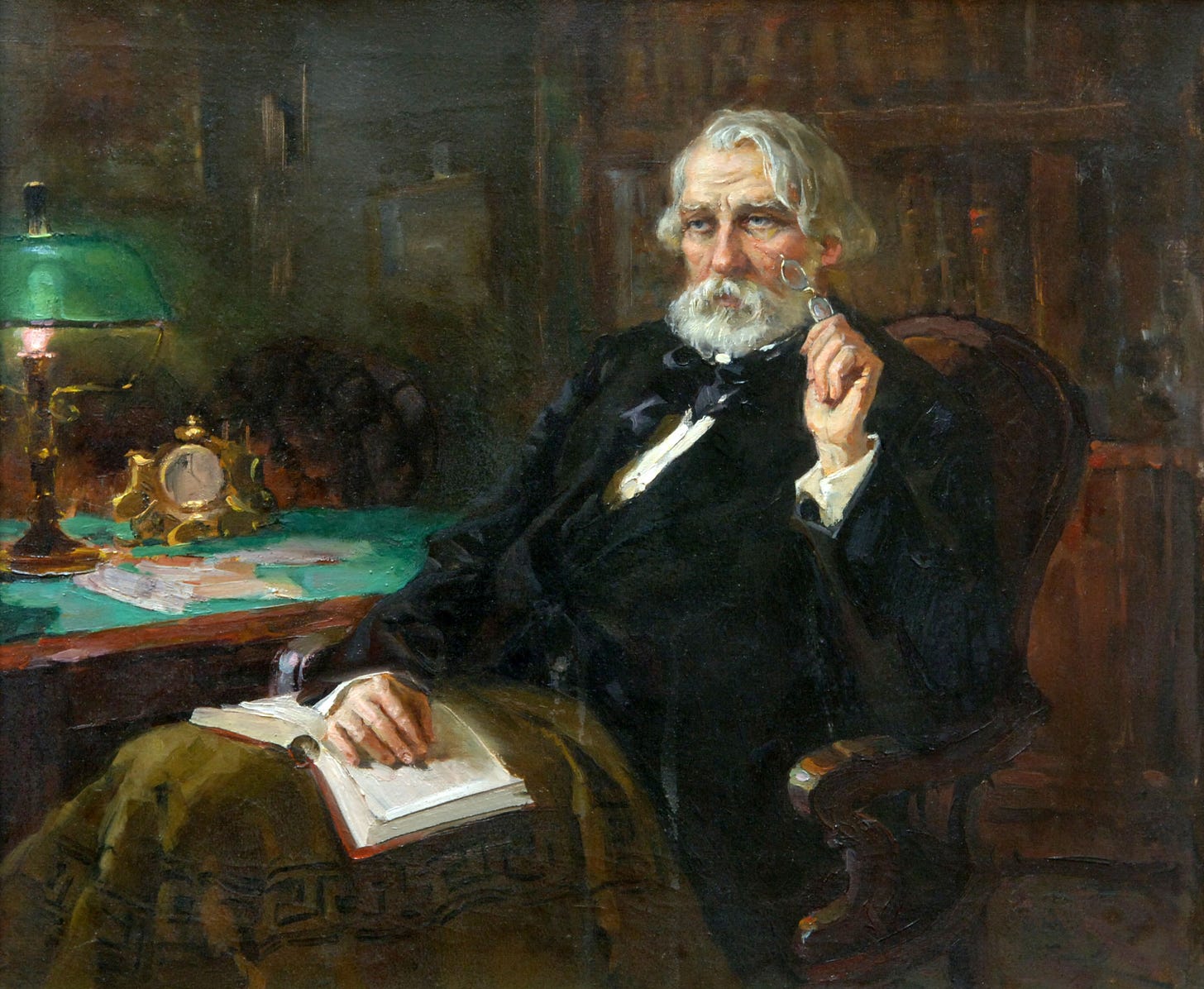

Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883)

Significance: A leading Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright, renowned for his lyrical realism and nuanced portrayals of Russian society. Turgenev introduced the concept of the “superfluous man” and coined the term “nihilist” in Fathers and Sons, influencing Russian and global literature. he is also known for his rivalry with Dostoevsky, with the latter dissecting Ivan’s ideology in a few of his novels.

Russia can do without any one of us, but none of us can do without her.

HPI value: 79.43

Attitudes towards Russian society: Recognized and disliked Russian backwardness. He advocated gradual reform over revolution, often clashing with radicals who found his approach too moderate.

Attitudes towards the West: Turgenev was a committed Westernizer, admiring Europe’s cultural achievements, democratic ideals, and intellectual freedoms. He spent much of his later life in Europe, particularly France and Germany, and was influenced by Western writers like Goethe and Flaubert. He believed Russia should adopt Western reforms—education, legal systems, and modernization—while preserving its cultural distinctiveness. However, he criticized the West’s materialism and was disillusioned by its failure to fully embody its own liberal ideals, as seen in his nuanced portrayals of Westernized Russians.

Philosophy: Humanism

Ideology: Liberalism. Reformism. Anti-Autocracy. Anti-Imperialist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian, had symbolic Tatar ancestry (less than 1%)

Religion: Nominally Russian Orthodox but highly skeptical and critical of the Church.

Family background: Born into a wealthy noble family in Oryol.

Government repression: Turgenev faced moderate government repression. His A Sportsman’s Sketches drew scrutiny for its anti-serfdom stance, leading to his brief arrest and month-long exile to his estate in 1852–1853, officially for an obituary praising Gogol but likely due to the book’s influence. His later works, like Fathers and Sons, faced censorship for their social critiques, but his international fame and moderate liberalism protected him from severe persecution.

Afanasy Fet (1820-1892)

Significance: Russia’s lyrical poet who is regarded as the finest master of lyric verse in Russian literature.

Without a sense of beauty, life is reduced to feeding hounds in a stuffy, foul-smelling kennel.

HPI value: 62.22

Attitudes towards Russian society: He idealized Russia’s rural, harmonious family life and “civil labor” as a natural link to the world, implicitly critiquing urban industrial society’s loss of harmony while avoiding direct engagement with class struggles or reforms.

Attitudes towards the West: Preferred Russia over the West

Philosophy: “art for art’s sake”, Escapism

Ideology: Apolitical. Focused on harmony.

Ethnicity: Great Russian father, German mother.

Religion: Russian Orthodox Christian

Family background: Born of illegitimate marriage. Father’s surname is Shenshin, by the end of his life this surname is returned to him.

Government repression: None.

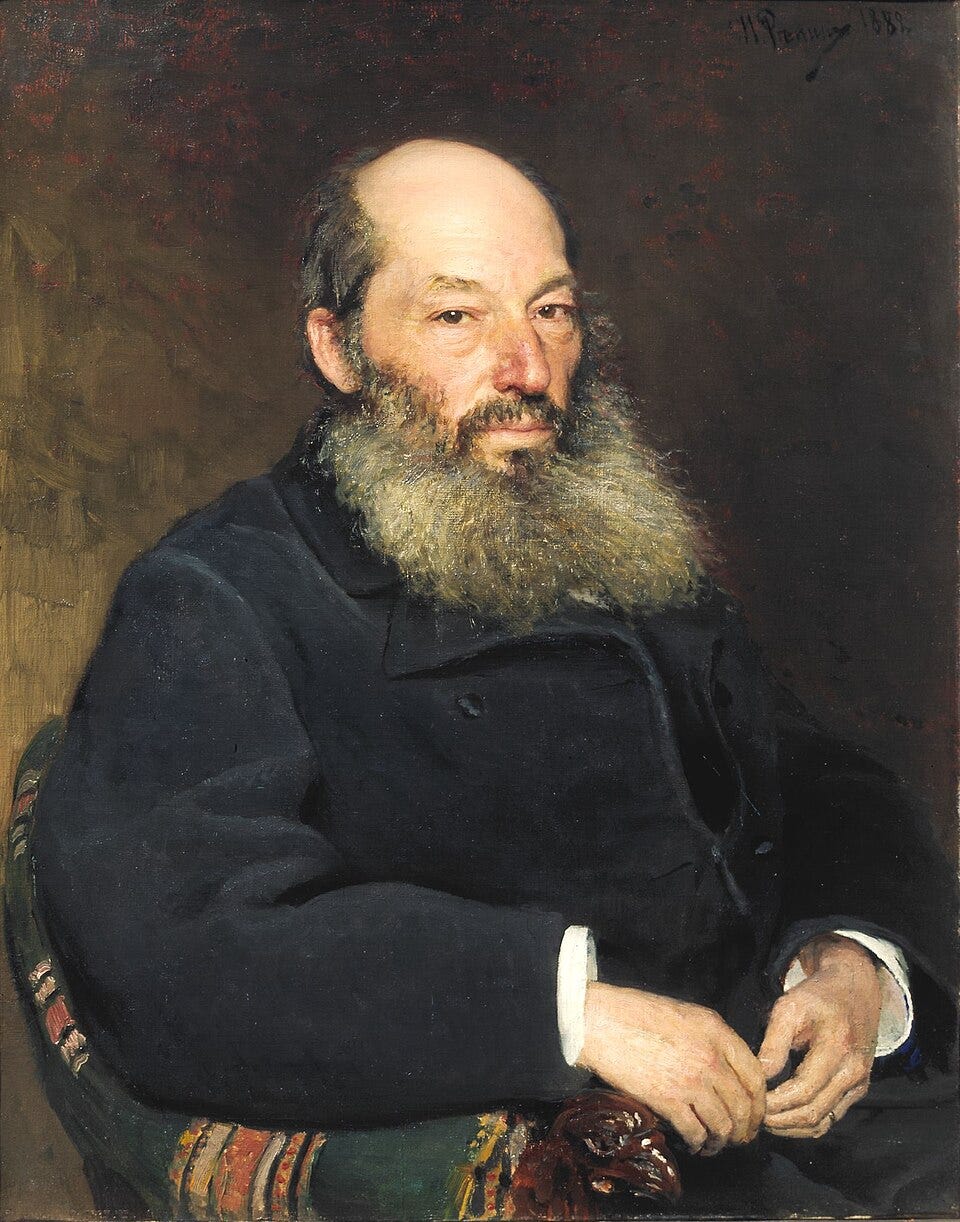

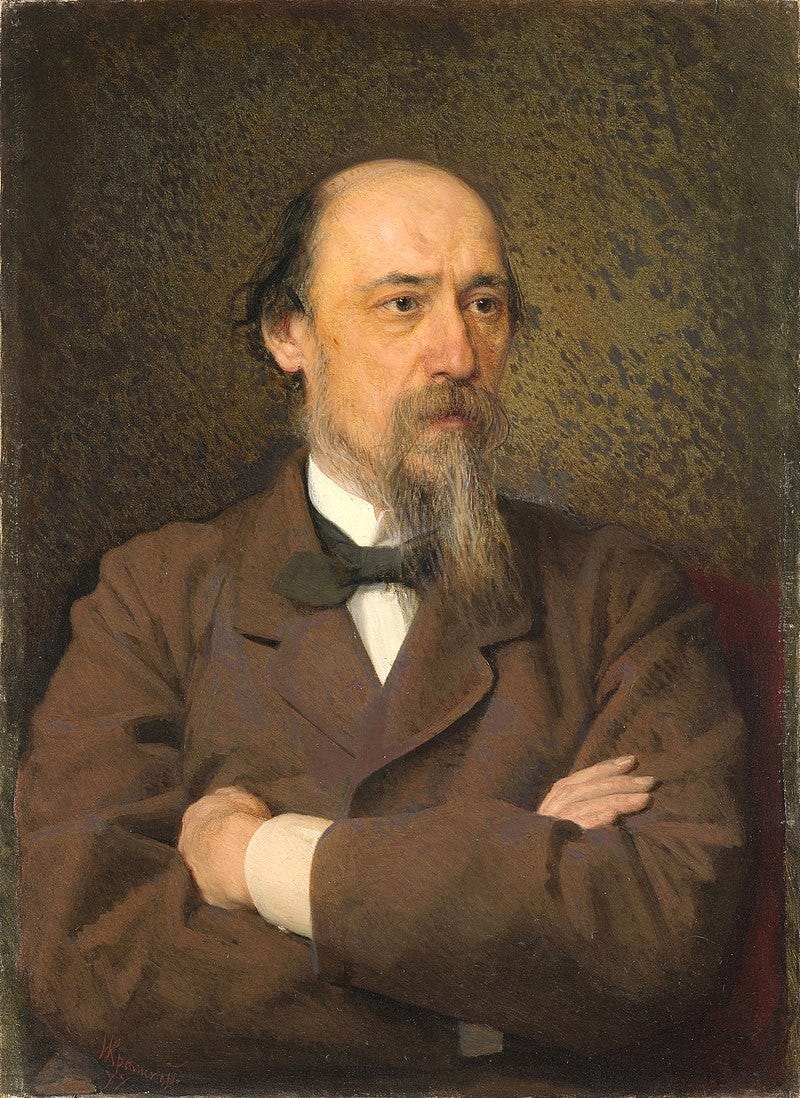

Nikolay Nekrasov (1821-1877)

Significance: A major Russian poet, critic, and publisher, often regarded as the “poet of the people” for his focus on the plight of the Russian peasantry. His epic poem Who Is Happy in Russia? (1863–1877) vividly portrayed the hardships of post-emancipation peasants, blending realism with social critique. As editor of the influential journals Sovremennik and Otechestvennye Zapiski, he shaped Russian literature by promoting writers like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. His poetry, rich in colloquial language and empathy for the oppressed, bridged Romanticism and realism, making him a big figure in 19th-century Russian literature.

A person is created to be a support for another, because they themselves need support.

HPI value: 67.69

Attitudes towards Russian society: Nekrasov was deeply critical of Russian society, particularly its feudal structures, autocratic oppression, and the exploitation of peasants. His works condemned the nobility’s indifference and the bureaucracy’s corruption, while celebrating the resilience and humanity of the lower classes. Despite his critiques, he expressed a profound love for Russia’s people and landscapes, advocating for social justice and reform.

Attitudes towards the West: Nekrasov admired Western liberal ideals, such as constitutional governance and individual freedoms, which he saw as models for Russian reform. He was influenced by Western writers like Victor Hugo, whose socially engaged literature resonated with him. However, he rejected blind Westernization, believing Russia’s unique cultural and communal traditions should guide its path to progress. He was wary of Western capitalism’s potential to deepen inequality in Russia, favoring a distinctly Russian approach to social change.

Philosophy: Realism, Civic-poetry

Ideology: Critic of Autocracy. Populist. Reformer. Sympathized with the Narodnik movement.

Ethnicity: 50% Great Russian, 50% Polish

Religion: Nominally Russian Orthodox but secular

Family background: Born in Ukraine to a Russian nobleman and a Polish daughter of a wealthy nobleman.

Government repression: His journal was frequently censored, and in 1866, it was shut down by the government for its progressive stance. Nekrasov was under surveillance, particularly after publishing works like The Railway, which criticized state-supported exploitation.

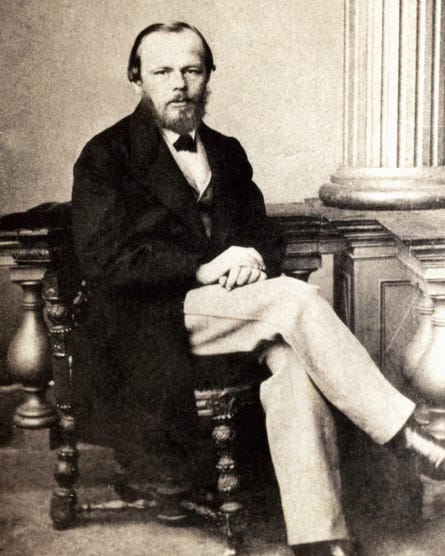

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881)

Significance: Is ranked as the second greatest writer of all time after Homer. His works enjoy wide-reaching influences all across the world, greatly contributing to existentialism, psychoanalysis, realism and moral dilemmas.

The destiny of the Russian person is, without doubt, all-European and universal. To become a true Russian, to become fully Russian, perhaps means only — to become a brother to all people, a universal human being, if you will. Our lot is universality, and not acquired by the sword, but by the power of brotherhood and our fraternal aspiration toward the reunification of people.

HPI value: 93.20

Attitudes towards Russian society: Dostoevsky was deeply critical of Russian society’s moral and spiritual decline, particularly the intelligentsia’s embrace of radical ideologies like nihilism and socialism, which he saw as eroding traditional values. He lamented the alienation of the elite from the peasantry, idealizing the latter’s faith and communal spirit as Russia’s moral core. Works like Demons critiqued revolutionary movements, while The Brothers Karamazov explored societal fragmentation. He advocated a return to Orthodox Christian values and social unity, believing Russia’s salvation lay in its spiritual heritage.

Attitudes towards the West: Dostoevsky was highly critical of the West, viewing its rationalism, materialism, and secularism as spiritually bankrupt.

Philosophy: Existentialism. Realism. Christian Ethics.

Ideology: Conservative Populist. Russian Nationalist. Russian Messianic Exceptionalism. Anti-Liberal and Anti-Socialist. Supporter of Autocracy. Pan-Slavist.

Ethnicity: Over 50% Great Russian. Then largely Belarussian with distant Polish, Russian and Tatar ancestry on his father’s side.

Religion: Russian Orthodox Christian (devout)

Family background: Born in Moscow to a middle-class noble family. His father, Mikhail Dostoevsky, was a retired military doctor who worked at a hospital for the poor; his mother, Maria Nechaeva, was a cultured, religious woman from a merchant family. Raised in a strict but intellectual household, Dostoevsky was exposed to literature early. His father’s murder by serfs in 1839 deeply affected him.

Government repression: In 1849, he was arrested for his involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle, a liberal discussion group, and charged with plotting against the state. Sentenced to death, he endured a mock execution before being exiled to a Siberian labor camp (1850–1854), followed by forced military service.

Alexander Ostrovsky (1823 - 1886)

Significance: Alexander Ostrovsky was a pivotal Russian playwright, often called the “father of Russian drama.” He wrote over 50 plays, including The Storm (1859) and Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man (1868), establishing a distinctly Russian theatrical tradition. His works, rooted in realism, depicted the lives of merchants, bureaucrats, and provincial families, exposing social flaws like greed, hypocrisy, and patriarchal oppression. Ostrovsky revolutionized Russian theater by focusing on everyday characters and vernacular speech, influencing later dramatists like Chekhov. He also co-founded the Russian Society of Dramatic Writers and Composers, advocating for artists’ rights.

The main tragedy in life is the cessation of struggle.

HPI value: 67.46

Attitudes towards Russian society: Ostrovsky was a sharp critic of Russian society, particularly the merchant class and provincial gentry. His plays exposed their moral failings—corruption, materialism, and domestic tyranny—while highlighting the struggles of women and the poor under rigid social structures. Works like The Storm critiqued patriarchal oppression, and Poverty Is No Vice (1854) idealized certain traditional Russian values like family loyalty. He sympathized with the underprivileged but avoided radical solutions, favoring cultural critique over political upheaval.

Attitudes towards the West: Ostrovsky had a reserved attitude toward the West. He appreciated Western literary forms, particularly Shakespeare and Molière, but believed Russian drama should reflect native traditions and language rather than mimic Western models. He was skeptical of Westernization’s impact on Russian identity, criticizing the superficial adoption of Western manners by the Russian elite. His focus remained on developing a distinctly Russian theatrical voice, rooted in local culture and folklore.

Philosophy: Realism

Ideology: Reformist, Liberal

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Devout Russian Orthodox but critical of clerical excesses

Family background: Born in Moscow to a middle-class family. Studied law at Moscow University but left without graduating, working as a court clerk, which informed his social observations.

Government repression: None

Alexaneder Afanasyev (1826-1871)

Significance: Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev was a Russian folklorist, historian, and scholar, best known for his monumental collection Russian Fairy Tales (Narodnye russkie skazki, 1855–1863), which preserved hundreds of Slavic folktales, myths, and legends, influencing Russian literature and global folklore studies. Often called the “Russian Grimm,” his work provided a foundation for understanding Slavic oral traditions, inspiring writers like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and later Soviet authors. His historical and mythological studies, such as Poetic Views of the Slavs on Nature (1865–1869), explored Slavic paganism and cultural identity, contributing to the 19th-century Russian intellectual revival and Slavophile thought.

A great writer is a martyr who survived, that’s all.

HPI value: 65.88

Attitudes towards Russian society: Afanasyev deeply valued Russia’s peasant culture and oral traditions, seeing them as the authentic soul of Russian identity, in contrast to the Westernized elite and bureaucratic autocracy of the tsarist regime. He criticized the alienation caused by modernization and Western reforms, aligning with Slavophile views that celebrated Russia’s communal, agrarian roots. While supportive of cultural preservation, he was critical of tsarist censorship and social injustices, advocating for intellectual freedom and the study of folklore as a means to reconnect with Russia’s spiritual heritage.

Attitudes towards the West: Skeptical and critical; Afanasyev viewed Western Europe’s rationalism, industrialization, and individualism as threats to Russia’s communal and spiritual traditions. While he respected Western scholarship (e.g., the Grimm brothers’ folklore work), he believed Russia’s unique cultural heritage, rooted in Slavic mythology and peasant life, was superior to Western materialism.

Philosophy: Mythopoetic. Romantic.

Ideology: Slavophile. Liberalism. Russian Nationalism. Pan-Slavism.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodoxy with Slavic Pagan elements

Family background: Born into a modest gentry family; son of Nikolai Ivanovich Afanasyev, a minor government official, and Varvara Ivanovna, from a similar provincial background. Raised in Voronezh, he received a solid education, studying law at Moscow University, where exposure to Romanticism and folklore scholarship shaped his career. His family’s gentry status provided intellectual opportunities but limited wealth, leading him to work as a librarian and archivist.

Government repression: Afanasyev faced tsarist censorship for his folklore collections, particularly Russian Secret Tales (Russkie zavetnye skazki), which included bawdy and subversive stories deemed inappropriate by authorities. His liberal views and association with intellectual circles critical of autocracy led to surveillance and professional restrictions. In 1860, he was dismissed from his archival post at the Moscow Main Archive due to suspected subversive activities.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin (1826-1889)

Significance: Most well-known Russian pessimist writer. Influenced Anton Chekhov.

If I fall asleep, wake up 100 years later and somebody asks me, what is going on in Russia, my immediate answer will be: drinking and stealing.

HPI value: 66.06

Attitudes towards Russian society: Saltykov-Shchedrin was fiercely critical of Russian society, particularly the autocratic system, corrupt bureaucracy, and the moral stagnation of the landed gentry. He saw the post-1861 serf emancipation as insufficient, exposing persistent social injustices and the greed of the elite. While sympathetic to the peasantry’s plight, he was skeptical of their passivity and the intelligentsia’s idealism, advocating reform through enlightened governance rather than revolution.

Attitudes towards the West: He admired Western liberal ideas, particularly constitutional governance and civic freedoms, as seen in his praise for European legal systems but disliked Western materialism.

Philosophy: Realism, Satire.

Ideology: Liberalism. Anti-Imperialist

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Nominally Russian Orthodox but a deep critic of it.

Family background: Born into a noble family in Spas-Ugol, Tver province. His father, Yevgraf Saltykov, was a stern, conservative landowner, and his mother, Olga Zabelina, came from a wealthy merchant family, creating a strict, hierarchical household

Government repression: In 1848, his early story A Tangled Affair led to his arrest and exile to Vyatka (1848–1855) under Nicholas I’s regime for its perceived subversive content. As a civil servant in Vyatka, he worked under surveillance but gained insights into bureaucratic corruption, fueling his later satires. His editorship of Otechestvennye Zapiski brought frequent clashes with censors, and the journal was shut down in 1884 due to government pressure.

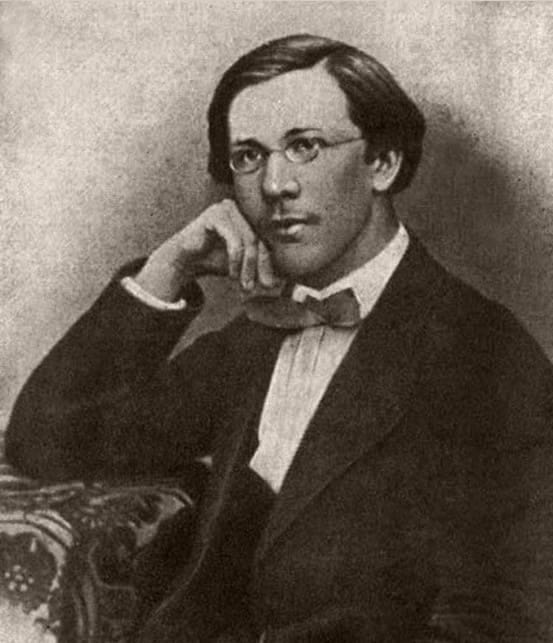

Nikolay Chernyshevsky (1828-1889)

Significance: Nikolay Chernyshevsky was a Russian philosopher, critic, novelist, and revolutionary thinker, a leading figure in the Russian radical intelligentsia. His novel What Is to Be Done? (1863), written in prison, became a manifesto for revolutionaries, inspiring generations, including Lenin and Xi Jingping. As a critic and editor of Sovremennik, he championed utilitarian art, arguing literature should serve social progress. His materialist philosophy and advocacy for socialism shaped the nihilist and populist movements, making him a pivotal figure in 19th-century Russian intellectual history.

Three qualities — extensive knowledge, the habit of thinking, and nobility of feelings — are necessary for a person to be educated in the full sense of the word.

HPI value: 70.40

Attitudes towards Russian society: Chernyshevsky was fiercely critical of Russian society, condemning autocracy, serfdom, and the aristocracy’s exploitation of the peasantry. He viewed the tsarist regime as oppressive and morally bankrupt, with the 1861 serf emancipation as inadequate. He idealized the peasantry’s potential for collective action, advocating radical social restructuring to achieve equality.

Attitudes towards the West: Chernyshevsky admired Western Enlightenment ideals, particularly rationalism, scientific progress, and socialist theories from thinkers like Fourier and Saint-Simon. He saw Western democratic and socialist models as inspirations for Russian reform, but he criticized Western capitalism for perpetuating inequality. He believed Russia could leapfrog Western industrial flaws by building socialism on its communal traditions (e.g., the obshchina), blending Western ideas with Russian realities to avoid bourgeois exploitation.

Philosophy: Utilitarianism. Rational Egoism. Materialism. Hegelianism.

Ideology: Revolutionary Socialist. Utopian and Peasant Socialism. Deeply influenced the Narodnik movement. Anti-Imperialist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian.

Religion: Atheist.

Family background: Born in Saratov to a priestly family. His father, Gavriil Chernyshevsky, was a liberal-minded Orthodox priest; his mother, Evgenia Golubeva, was devout and nurturing. Educated at home and in a seminary, Chernyshevsky rejected a clerical path, enrolling at St. Petersburg University to study history and philosophy.

Government repression: His radical writings in Sovremennik and leadership in intellectual circles led to his arrest in 1862 for suspected revolutionary activities. Without concrete evidence, he was sentenced to seven years of hard labor in Siberia, followed by lifelong exile (1864–1883). He wrote What Is to Be Done? in prison, smuggled out for publication. His exile, marked by harsh conditions, broke his health, and though allowed to return to Saratov in 1883, he remained under surveillance until his death.

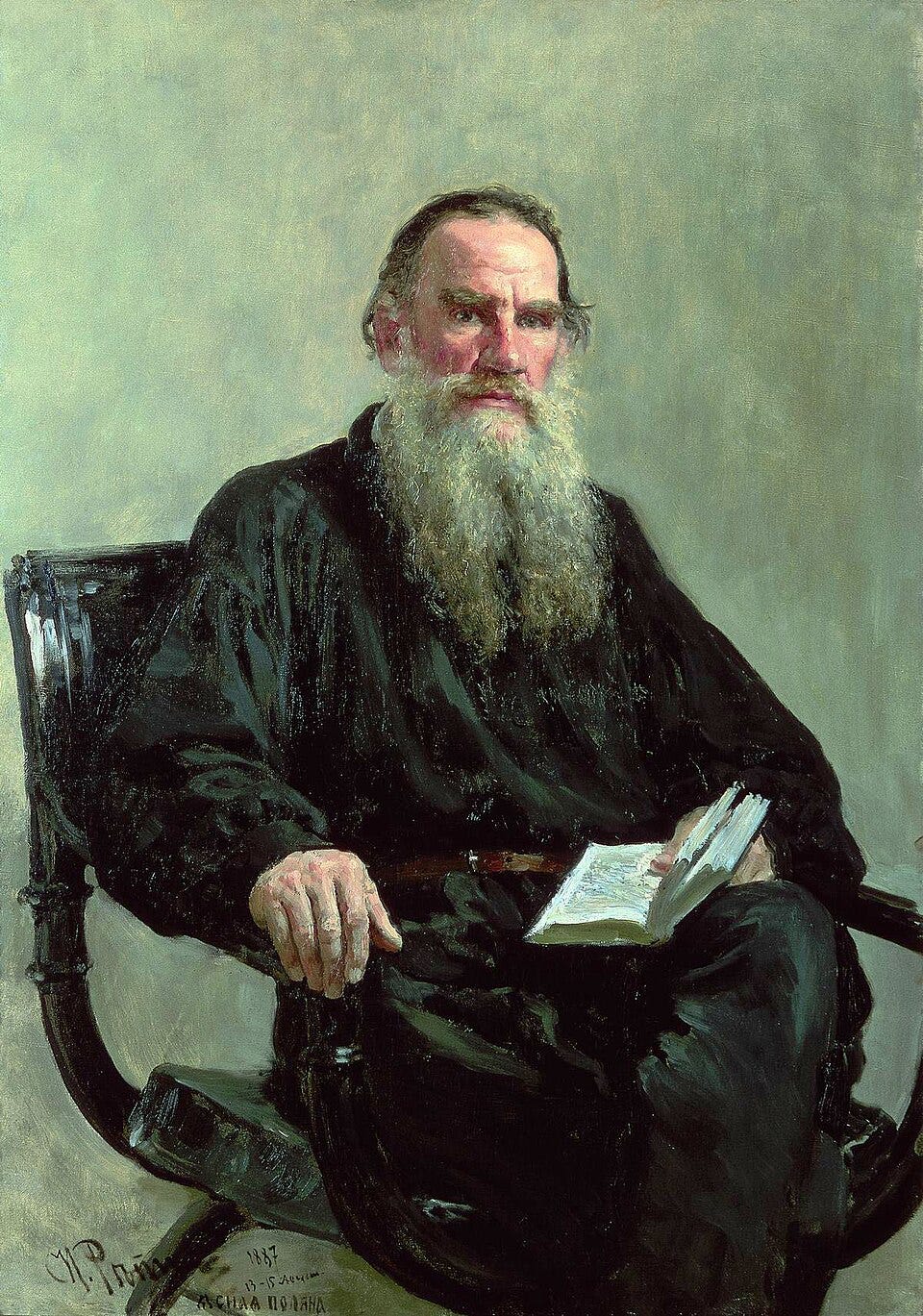

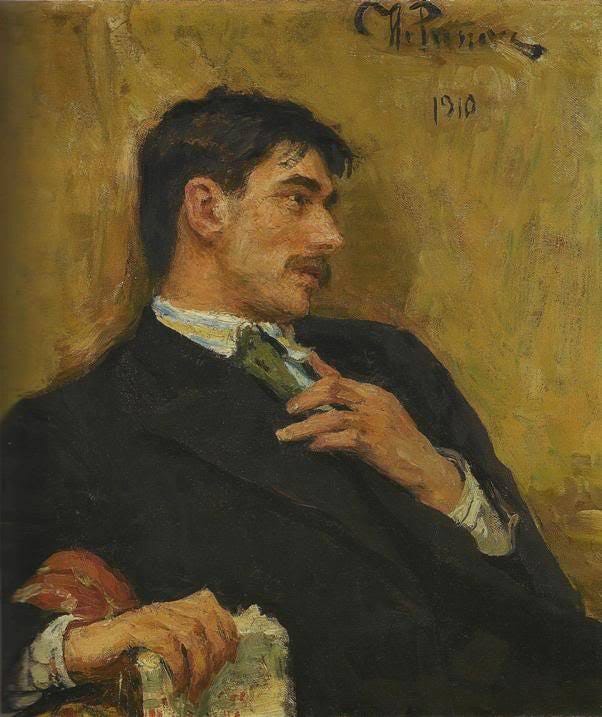

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910)

Significance: He is regarded as one of the greatest and most influential authors of all time, renowned for masterpieces like War and Peace (1865–1869) and Anna Karenina (1875–1877), which blend epic scope, psychological depth, and moral inquiry.

Patriotism, in its simplest, clearest, and most unquestionable meaning, is nothing other for rulers than a tool for achieving ambitious and selfish goals, and for the governed — a renunciation of human dignity, reason, conscience, and slavish submission to those in power. This is how it is preached wherever patriotism is preached. Patriotism is slavery.

HPI value: 89.82

Attitudes towards Russian society: Tolstoy was highly critical of Russian society, particularly the aristocracy’s decadence, the bureaucracy’s corruption, aggressive expansion and the Orthodox Church’s complicity in autocratic oppression. He idealized the peasantry’s simplicity and moral purity, as seen in his later writings and lifestyle experiments at Yasnaya Polyana. He condemned serfdom (abolished in 1861) and later criticized the inequalities of post-reform Russia, advocating for social justice and land reform. His rejection of state authority and societal hierarchies alienated him from both elites and radicals.

Attitudes towards the West: Tolstoy was skeptical of the West, criticizing its materialism, industrialization, and militarism as spiritually hollow. While he admired Western literature (e.g., Rousseau, Dickens) and Enlightenment ideas in his youth, he later rejected Western individualism and capitalism, believing they fostered greed and alienation. He saw Russia’s communal traditions and peasant wisdom as morally superior, though he selectively appreciated Western philosophical ideas that aligned with his views on universal ethics and nonviolence.

Philosophy: Initially realism. Then Christian anarchism. Tolstoyism.

Ideology: Pacifist. Christian Anarchism. Anti-Imperialist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Tolstoyism but formerly Russian Christian Orthodox.

Family background: Born to an aristocratic family. Educated in Kazan University.

Government repression: Tolstoy faced significant government repression for his radical views. His later writings, like What I Believe (1884), were banned for their anti-state and anti-church stance. The Orthodox Church excommunicated him in 1901, and his works were heavily censored. He was under surveillance by the tsarist secret police, who feared his influence on revolutionary sentiment, though his international fame and aristocratic status protected him from arrest or exile.

Nikolai Leskov (1831-1895)

Significance: Nikolai Leskov was a prominent Russian novelist, short story writer, and journalist, celebrated for his vivid storytelling, linguistic richness, and portrayal of Russian provincial life. Leskov’s focus on marginalized voices and moral complexities made him a unique figure in Russian literature. Influenced Chekhov and Sholokhov.

Faith is a luxury that costs people dearly.

HPI value: 67.44

Attitudes towards Russian society: Leskov had a complex relationship with Russian society, admiring its cultural richness and spiritual depth while critiquing its injustices and rigid hierarchies. He championed the resilience and ingenuity of ordinary Russians, particularly peasants and provincial figures, as seen in stories like The Steel Flea (1881). However, he criticized the corruption of the bureaucracy, the hypocrisy of the Orthodox Church’s elite, and the gentry’s detachment from the masses. Unlike radical contemporaries, he advocated reform through moral and cultural renewal rather than revolution, showing a deep affection for Russia’s traditions.

Attitudes towards the West: Leskov was ambivalent toward the West. He respected Western technological progress and intellectual freedoms, but he distrusted its secular materialism and perceived moral decay, believing Russia’s spiritual traditions offered a counterbalance. His travels in Europe (1861–1863) informed works like No Way Out (1864), where he critiques Westernized Russian intellectuals for their superficiality

Philosophy: Christian Ethics, Realism.

Ideology: Anti-Imperialist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox Christian

Family background: Born in the Oryol province, to a modest noble family. Educated in Oryol Gymnasium.

Government repression: His journalism, particularly in Northern Bee and later publications, often clashed with censorship authorities, resulting in occasional bans on his articles.

Nikolay Dobrolyubov (1836-1861)

Significance: A prominent figure of the Russian revolutionary movement. analyzed literature as a tool for social reform, critiquing Russian societal stagnation and advocating for change. His incisive reviews shaped the civic criticism movement, influencing the revolutionary zeal of the era including Karl Marx.

A man who hates another nation does not love his own.

HPI value: 63.79

Attitudes towards Russian society: Dobrolyubov was a fierce critic of Russian society, condemning its autocratic oppression, serfdom, and the inertia of the gentry and bureaucracy. He saw the aristocracy’s apathy (epitomized by “Oblomovism”) and the Orthodox Church’s complicity as barriers to progress. He championed the peasantry’s potential for reform, believing their liberation and education could transform Russia. His essays called for dismantling feudal structures and fostering a society based on equality and rational progress, reflecting a radical commitment to social justice.

Attitudes towards the West: Dobrolyubov admired Western Enlightenment ideals, particularly rationalism, democracy, and socialist thought from figures like Fourier. He viewed Western liberal institutions as models for Russian reform, advocating the adoption of scientific and educational advancements. However, he criticized Western capitalism’s inequalities and was cautious about uncritical Westernization, believing Russia could develop a progressive society rooted in its communal traditions, like the peasant obshchina, while drawing selectively from Western ideas.

Philosophy: Materialism. Utilitarianism.

Ideology: Radical socialist with revolutionary leanings. Agrarian Socialism. Anti-Imperialist.

Ethnicity: Great Russian.

Religion: Atheist

Family background: Born in Nizhny Novgorod to a priestly family. His father, Alexander Dobrolyubov, was an Orthodox priest, and his mother, Zinaida Pokrovskaya, was devout, raising him in a religious but intellectually open household. Educated at a clerical school and later at the St. Petersburg Pedagogical Institute, he rebelled against his religious upbringing, embracing radical ideas.

Government repression: None.

Mikhail Bakhunin (1814-1876)

Significance: Mikhail Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary, philosopher, and theorist, widely regarded as a founding figure of left wing anarchism. His ideas influenced Russian populism, global anarchism, and later revolutionary movements, cementing his legacy as a radical thinker.

Freedom without socialism is privilege, injustice; socialism without freedom is slavery.

HPI value: 82.22

Attitudes towards Russian society: Bakunin fiercely criticized Russian society’s autocratic tsarist regime, serfdom, and bureaucratic oppression, viewing them as tools of elite domination. He condemned the Orthodox Church for supporting autocracy and stifling freedom. However, he idealized the Russian peasantry, seeing their communal traditions (obshchina) and history of rebellions (e.g., Pugachev’s uprising) as a foundation for revolutionary change. He believed Russia’s masses could lead a stateless, egalitarian revolution, bypassing Western-style industrialization.

Attitudes towards the West: Bakunin had a nuanced view of the West. He admired its revolutionary heritage, particularly the French Revolution, and engaged with Western philosophers like Hegel and Proudhon, drawing inspiration from their ideas. He spent much of his life in Western Europe, participating in uprisings like the 1848 revolutions. However, he criticized Western capitalism, parliamentary democracy, and centralized states as new forms of oppression, arguing they betrayed revolutionary ideals. He believed the West’s working classes and peasants held revolutionary potential, but he saw Russia’s communal traditions as a unique advantage.

Philosophy: Nihilism, Anarchism

Ideology: “Collective Anarchism”, Socialism, Anti-German and Anti-Semitic sentiment, Anti-Imperialist

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Atheist

Family background: Born into a noble family in Pryamukhino, Tver province. His father, Alexander Bakunin, was a liberal landowner and retired diplomat; his mother, Varvara Muravyeva, came from a noble family. Raised in a cultured, reform-minded household, Bakunin was educated at home before attending a military school in St. Petersburg, which he left to pursue philosophy.

Government repression: His radical activities led to multiple arrests: in Russia in 1840 for revolutionary associations, resulting in surveillance and eventual emigration in 1841; and across Europe for participating in uprisings (e.g., Dresden, 1849). After his 1849 arrest in Saxony, he was extradited to Russia in 1851, where he was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress and later exiled to Siberia (1855–1861). He escaped Siberia in 1861, continuing his revolutionary work abroad. The tsarist regime banned his writings, and his émigré status made return impossible.

Vsevolod Garshin (1858-1888)

Significance: A short story writer, known for his psychologically intense and morally charged narratives that captured the emotional toll of war, human suffering, and mental instability. Garshin’s concise, empathetic style and focus on individual consciousness made him a precursor to modernist literature, influencing writers like Chekhov. Despite his short life, his work left a lasting mark on Russian realism.

War is a common grief, a common suffering.

HPI value: 63.03

Attitudes towards Russian society: Garshin was critical of Russian society, particularly its militarism and the societal pressures that exacerbated human suffering. His stories often depict the dehumanizing effects of war and bureaucracy, reflecting a deep sympathy for ordinary individuals—soldiers, peasants, and the marginalized. He mourned the moral and psychological costs of Russia’s imperial ambitions, as seen in his anti-war narratives, but avoided broad social critiques, focusing instead on personal and existential struggles. His work suggests a disillusionment with societal norms that prioritized duty over humanity.

Attitudes towards the West: He was influenced by Western literary traditions, particularly the psychological realism of writers like Edgar Allan Poe and the moral introspection of European Romantics. However, he showed little interest in Western political or social models, focusing instead on universal human experiences. His war stories implicitly critique the glorification of military campaigns, whether Russian or Western, suggesting a skepticism of imperial and nationalist ideologies across cultures.

Philosophy: Universalism and pacifism.

Ideology: Pacifism. Anti-Imperialism

Ethnicity: Great Russian

Religion: Russian Orthodox

Family background: Born in Bakhmut to a noble family of Russian descent. His father, Mikhail Garshin, was a retired army officer and landowner; his mother, Yekaterina Akimova, was educated and progressive, later leaving the family for a revolutionary activist, which deeply affected Garshin. Raised in a cultured but turbulent household, he suffered from mental health issues, likely exacerbated by family instability. Educated in St. Petersburg, he briefly studied mining engineering but turned to writing.

Government repression: None.

Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900)

Significance: Solovyov was a Russian philosopher, poet, theologian, and literary critic, often considered the founder of Russian religious philosophy. His synthesis of Christian mysticism, idealism, and universalism profoundly shaped Russian thought. His ecumenical ideas and critique of nationalism also prefigured modern Christian existentialism.