People Are Not Selfish

People are more altruistic than selfish

This is going to the second or third part of my series on morality (if you want to include my article on intelligent people being less moral as part of the series).

But first I’d like to clarify that humans, just like other animals, have both instincts for altruism and selfishness, and that these two predispositions both work in combination with one another; however, when we are in a group setting, most people act altruistically. Because natural variation exists between animals shaped by individual-level and group-level selection, different species fall along opposite ends of this spectrum—with the common cuckoo representing the highly selfish extreme, and honeybees and ants embodying the most group-oriented extreme. Humans, due to their exceptional pro-social tendencies, align more closely with honeybees and ants than with cuckoos, though they still retain the capacity for selfishness (to varying degrees) determined by their innate biology and socialization.

Jonathan Haidt puts it like this:

I will suggest that human nature is mostly selfish, but with a groupish overlay that resulted from the fact that natural selection works at multiple levels simultaneously. Individuals compete with individuals, and that competition rewards selfishness... But at the same time, groups compete with groups, and that competition favors groups composed of true team players—those who are willing to cooperate and work for the good of the group, even when they could do better by slacking, cheating, or leaving the group.

Now I don’t entirely agree with Jonathan Haidt here, because of overwhelming evidence that putting teammates against each other is overall much less efficient than group competition, although I won’t dispute that individual competition is useful, though I would mostly describe it as the battle for prestige as Ricardo Duchesne has, as opposed to “race wars” and “group hatred” and culture wars which often define group competition.

Funny enough, as Jonathan Haidt later admits in the book:

“Intergroup competitions, such as friendly rivalries between corporate divisions, or intramural sports competitions, should have a net positive effect on hivishness and social capital. But pitting individuals against each other in a competition for scarce resources (such as bonuses) will destroy hivishness, trust, and morale.”

Precisely because competition between individuals tends to be less effective and less sustainable than competition between groups, we already have reason to question Rand’s claim that rational self-interest should serve as the foundation of morality. The empirical evidence suggests that human beings often thrive not by undermining one another, but by coordinating within teams that compete collectively. Moreover, even in experimental settings where the rules of the game strongly discourage cooperation and heavily incentivize selfish behavior, a significant number of people still choose to cooperate—sometimes at real personal cost.

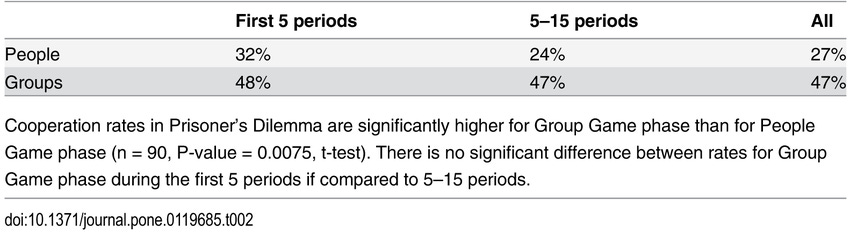

The results showing much higher Prisoner’s Dilemma cooperation while in a group are consistent with my earlier claim that humans are more cooperative and less selfish in social settings than they are alone. In moments like this, they are ready to make sacrifices for the benefit of the group and at the cost of themselves.

As a war historian recounts:

Many veterans who are honest with themselves will admit, I believe, that the experience of communal effort in battle … has been the high point of their lives.… Their “I” passes insensibly into a “we,” “my” becomes “our,” and individual fate loses its central importance.… I believe that it is nothing less than the assurance of immortality that makes self sacrifice at these moments so relatively easy.… I may fall, but I do not die, for that which is real in me goes forward and lives on in the comrades for whom I gave up my life.

Jonathan Haidt labels this mechanism the “hive switch” or as [the ability (under special conditions) to transcend self-interest and lose ourselves (temporarily and ecstatically) in something larger than ourselves]. It is a form of a group-level adaptation which has a function of numbing an individual’s selfish desires and activating his altruistic traits for the purpose of group cohesion. Think of a reproductive suicide of the worker bee for the sake of the queen or the suicidal defense of the hive when a worker bee stings an intruder, ripping its own abdomen. The human equivalent of that would be a religious self-sacrifice, kamikaze attacks or other forms of self-sacrifice.

These sacrifices are never pursued for selfish ends and are usually done for the sake of the survival of a group or some higher moral ideal like religion or politics.

But these are extreme cases. You see… Self-sacrifice involving death is rare enough that every case of it becomes news. Meanwhile, most altruistic acts go on a day-to-day basis. As one research paper opens up:

One doesn’t have to observe humans in their natural habitat for long to witness many and varied examples of prosocial behavior, often directed towards complete strangers. People might vacate a seat on a crowded bus or train to let an elderly person sit down; hold open a door for others; or help a struggling parent to carry their pram down a flight of stairs. Humans also willingly donate resources, such as money or food, to others for example by giving to charity... This propensity to help unrelated others who reside outside our regular social circle is striking when one considers that these helpful acts are seemingly unobserved and many of the interactions are unlikely to persist beyond the current round.

and..

Humans regularly help strangers, even when interactions are apparently unobserved and unlikely to be repeated. Such situations have been simulated in the laboratory using anonymous one-shot games (e.g., prisoner’s dilemma) where the payoff matrices used make helping biologically altruistic. As in real-life, participants often cooperate in the lab in these one-shot games with non-relatives, despite that fact that helping is under negative selection under these circumstances.

The key idea is that humans have developed to prioritize maintaining their larger community and the social order, often at a personal cost.

This tendency toward self-sacrifice for the sake of the group stems from our evolutionary roots, where cooperation and group survival often outweighed individual gain. Early human societies relied on mutual trust and collective effort to thrive, and those who prioritized the group’s well-being over their own were more likely to contribute to a stable, successful community. Over time, this behavior became ingrained, shaping our instincts and social structures to value altruism, even when it demands personal sacrifice. Our moral system is specifically tailored to punish and kick selfishness, rule violators and traitors out of the group, often at a cost to ourselves.

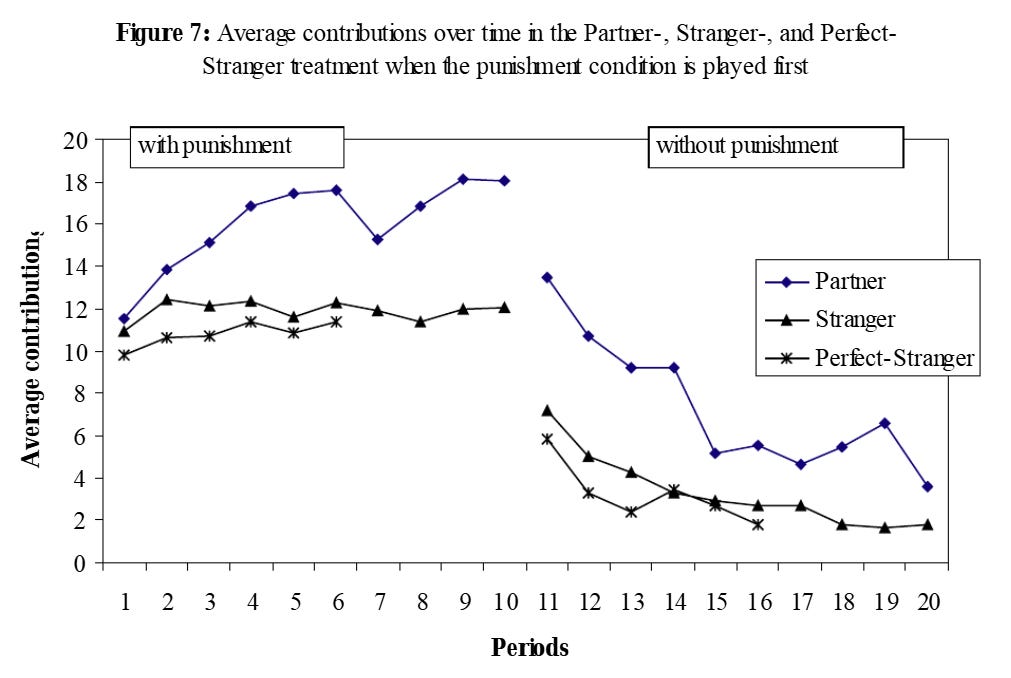

In other words, while humans have both instincts for altruism and selfishness, in a group environment, humans become more altruistic because it is to the advantage of the group to encourage more cooperation and contribution from each member. As a result group members are punishing free-riders even at a cost to themselves.

Anthropologist Richard Sosis examining the history of two hundred communities founded in the nineteenth century has found that “just 6 percent of the secular communes were still functioning twenty years after their founding, compared to 39 percent of the religious communes”.

The religious communities have survived because they had demanded sacralized acts of sacrifice from their members whereas secular communities either did not demand a sacrifice or their demands of sacrifice weren’t perceived as sacred. In other words, the rational “cost-benefit” calculation has doomed their communities, whereas “irrationality” has helped the religious group to function rationally.

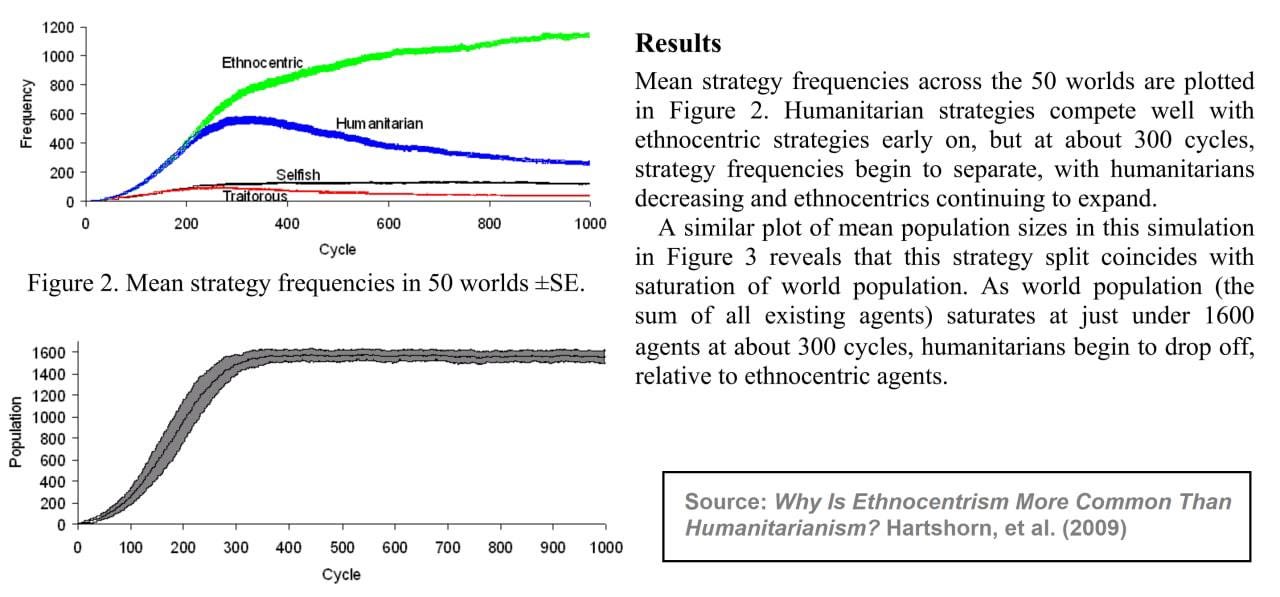

Likewise, computer models have repeatedly shown the complete maladaptability of selfish survival strategies and the total dominance of ethnocentric group survival strategies.

Out of all iterations, agents adopted an ethnocentric approach in 75% of the cases, while adopting a selfish approach or acting in their own self-interest in just 8% of the cases.

Charles Darwin explains this logic perfectly in the Descent of Man:

When two tribes of primeval man, living in the same country, came into competition, if (other circumstances being equal) the one tribe included a great number of courageous, sympathetic and faithful members, who were always ready to warn each other of danger, to aid and defend each other, this tribe would succeed better and conquer the other. Let it be borne in mind how all-important in the never-ceasing wars of savages, fidelity and courage must be. The advantage which disciplined soldiers have over undisciplined hordes follows chiefly from the confidence which each man feels in his comrades. Obedience, as Mr. Bagehot has well shewn, is of the highest value, for any form of government is better than none. Selfish and contentious people will not cohere, and without coherence nothing can be effected. A tribe rich in the above qualities would spread and be victorious over other tribes: but in the course of time it would, judging from all past history, be in its turn overcome by some other tribe still more highly endowed. Thus the social and moral qualities would tend slowly to advance and be diffused throughout the world.

These mechanisms of sociality have evolved in us so deeply, that we experience negative emotions ourselves when strangers are being mistreated. Studies have highlighted the role of negative emotions, particularly anger, in driving these punishments. When individuals witness a norm violation, such as an unfair distribution of resources, it can trigger strong negative feelings that motivate them to punish the transgressor, even with no direct benefit to themselves.

This brings me to one explanation for this phenomenon, which arises from the co-evolution of groups and individuals. Our innate capacity to relate to others has fostered greater altruism, as humans have evolved to prioritize group cohesion and cooperation, often placing the needs of the collective above their own. Jonathan Haidt has advanced the thesis that mirror-neurons are one of the main triggers for pro-social behavior, due to their effective transmission of stranger’s intentions and peace of mind:

People feel each other’s pain and joy to a much greater degree than do any other primates. Just seeing someone else smile activates some of the same neurons as when you smile. The other person is effectively smiling in your brain, which makes you happy and likely to smile, which in turn passes the smile into someone else’s brain.

Psychologist Daniel Batson constructed an entire theory around this, calling it the empathy-altruism hypothesis, which argues that when individuals feel empathy for someone in need, they act out of genuine concern rather than self-interest. Its main assumption is that altruism comes from an ability to feel empathetic emotions and a sense of relatedness, rather than self-interest.

In one of Batson's studies, participants were required to read notes from Janet Arnold, a lonely freshwoman, and were given the chance to volunteer time to befriend her. Those instructed to imagine Janet’s feelings (high-empathy group) offered significantly more time to help than those told to remain objective (low-empathy group), even when their decisions were anonymous and free from social judgment.

Batson has also conducted experiments to evaluate whether altruistic behavior stems from egoistic or empathetic motives, testing if people help others to reduce their own discomfort or out of genuine concern. In these studies, participants could volunteer to take electric shocks for a confederate worker, with conditions varying by ease of avoiding the distressing sight and level of empathy induced. Results showed participants helped equally in both easy and difficult escape conditions when empathy was high, indicating altruistic motives drive helping behavior, not egoistic desires to reduce personal distress.

Other studies seem to confirm this. To quote an abstract from one of them:

We conducted two studies to test this claim. In Study 1 subjects were led to believe that no one--including the person in need--would ever know if they declined to help. In this situation, which was designed to be totally devoid of the potential for negative social evaluation for not helping, there was still a positive relationship between self-reported empathic emotion and offering help. In Study 2 empathy (low versus high) and social evaluation (low versus high) were manipulated in a 2 X 2 design. Once again there was a positive relationship between empathy and offering help when the potential for social evaluation was low as well as high. Results of both studies, then, suggest that the motivation to help evoked by empathy is not egoistic motivation to avoid negative social evaluation. Instead, the observed pattern was what would be expected if empathy evokes altruistic motivation to reduce the victim's need.

Likewise, studies out of Israel have confirmed that individuals with higher empathy scores were significantly more willing to become organ donors among other things.

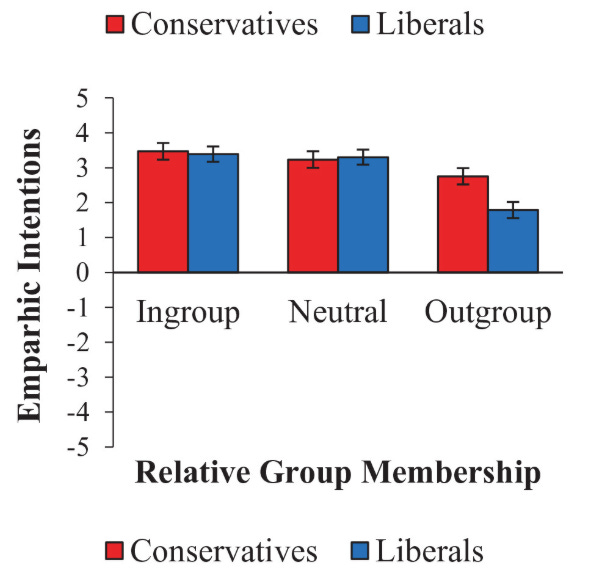

Finally, to bring this up to the realm of politics - the moral foundations theory helps explain why conservatives can empathize with liberals, but not vice versa: liberals’ narrower and imbalanced moral foundations leave them unable to fully grasp the moral reasoning that guides conservatives. As the New Yorker summarizes:

Liberals have come to rely almost exclusively on their fairness and empathy modules, allowing the others to atrophy. Conservatives, by contrast, tend to keep all their modules up and running.

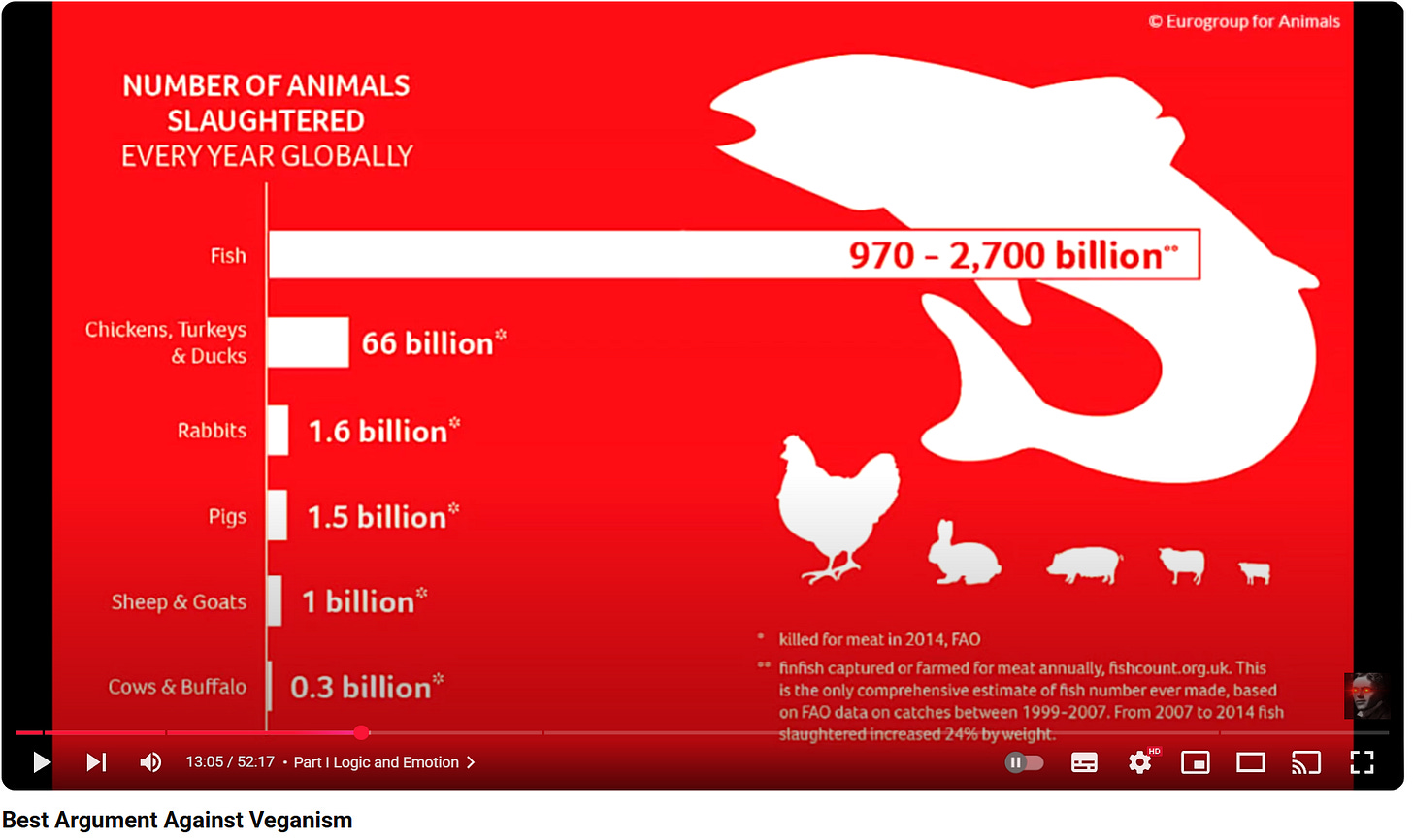

Likewise, as I have pointed out in my video critique of the vegan ideology, vegans tend to fixate on mammals and other highly developed animals, like cows or goats, whose emotions humans can recognize and empathize with, while largely neglecting fish and more primitive creatures, simply because we struggle to read their emotions—even though, as I explain in my video, they make up most of the casualties.

That is to say, empathy and mirror neurons, emerging from the co-evolution of group and individual dynamics, are the primary biological prerequisite for altruistic behavior.

To quote a well-respected philosopher of morality Richard Joyce:

All the empirical evidence shows that humans are often motivated by genuine regard for others, and not ultimately by selfish motives (Pilliavin and Charng 1990; Batson 1991, 2000; Ray 1998). Perhaps surprisingly, some of this evidence comes from observations of how humans are willing to punish transgressors even at material cost to themselves—and even when they are unaffected observers of the transgression (Fehr and Fischbacher 2004; Knutson 2004; Carpenter et al. 2004). The opposing view seems to me (if an ad hominem comment may be excused) to be generally motivated by a certain cynical attitude about human behavior, and is not based on any real empirical foundation.

Now, the chief error in claiming that humans are inherently selfish lies in viewing Darwinism solely through individualistic or kin-based frameworks, ignoring the possibility of selection at the group level.

If evolution indeed occurs solely on the individual level, then surely survival strategies, that would further maximize the relative advantage of the individual against the group would proliferate, but evolutionary mechanisms of guilt, laughter, self-sacrifice and suicide paint a completely different picture. Furthermore, the reproduction system itself is specifically tailored for group level-selection as opposed to an individual one. With each new generation after reproduction, a supposedly selfish individual loses 50% of “his” (his group’s) unique DNA. With as little as 6-8 generational iterations no visible trace of the original person choosing to kick off this reproduction chain remains, yet the group endures, and the once-“unique” genes of that individual persist only as fragments, endlessly recombining in clustered iterations across the broader population. That was the case before he was born and that will be the case after.

Evolution is not individual-centric, but occurs on multiple dimensions at once including the group, from which an individual finds a mate. Darwin has never maintained that selection occurred only on the individual level which seems to be a contemporary and XXth century heresy that is slowly moving out of academia due to contemporary findings. To quote a contemporary paper in evolution:

One of the strengths of group selection is that it is able to explain why certain types of behavior in both human and non-human animals have not been eliminated by natural selection, even though they incur a fitness cost to the individual animal. A clear example of this is altruism, which can be defined as any behavior that somehow benefits some other organism, while at the same time reducing the likelihood that the animal that acts altruistically will reproduce. Darwin and other group selectionists following him have argued that a group containing altruists that are prepared to behave in a manner that is detrimental to their own fitness but for the good of the group, may have an evolutionary advantage over groups without such members—which means that group selection can account for the Darwinian puzzle that is the existence of altruists: “a tribe including many members who […] were always ready to give aid to each other and sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection” (Darwin, 1871, 166). This may perhaps be why multilevel selection theory is seeing an increasing number of adherents in the scientific community (Yaworsky, Horowitz et al. 2015).

The resurgence of group-selection is not merely an academic shift; it is a fundamental correction to a flawed, century-long narrative that has distorted our understanding of ourselves. The 20th-century cultural shift toward selfishness was largely reinforced by influential scientific and social theories that emerged after the First and Second World Wars. However, these individual-centric theories were poorly supported then and even more so now.

This brings us back to a crucial question from the previous article in this series: why might more intelligent people sometimes appear less moral? If our morality is built upon the intuitive, empathetic, and group-oriented mechanisms we've explored, then perhaps high intelligence provides the cognitive tools to override them. It allows for the complex rationalization of self-interest, constructing elaborate justifications to defect from the cooperative norms that bind the rest of us through feeling and instinct. This is why many intelligent people also tend to be sympathetic to the self-interested view of human cooperation.

It is my personal observation that many Biorealists as well as many thought leaders of the Radical and Dissident Right, happen to be narcissistic and selfish in addition to also being highly intelligent. This psychological profile makes them intellectually receptive to a worldview that frames selfishness as the fundamental human reality.

Ultimately, to understand morality is to abandon the cynical caricature of the purely selfish actor. We are not cuckoos, and we are not ants, but a complex fusion of both—creatures (although much closer to ants than cuckoos) of self-interest profoundly shaped by an even deeper, more powerful need to belong, to cooperate, and to serve a purpose larger than ourselves. Our moral systems are a product of the symbiotic co-evolution of the group and the individual.