Political Views of Russian Canadians

Very Socially Conservative and...

I recently did an interview with a Russian YouTuber (in Russian) about various things related to Canada, including the circumstances of Russian Canadians, which should be uploaded on his YouTube or Telegram channel soon.

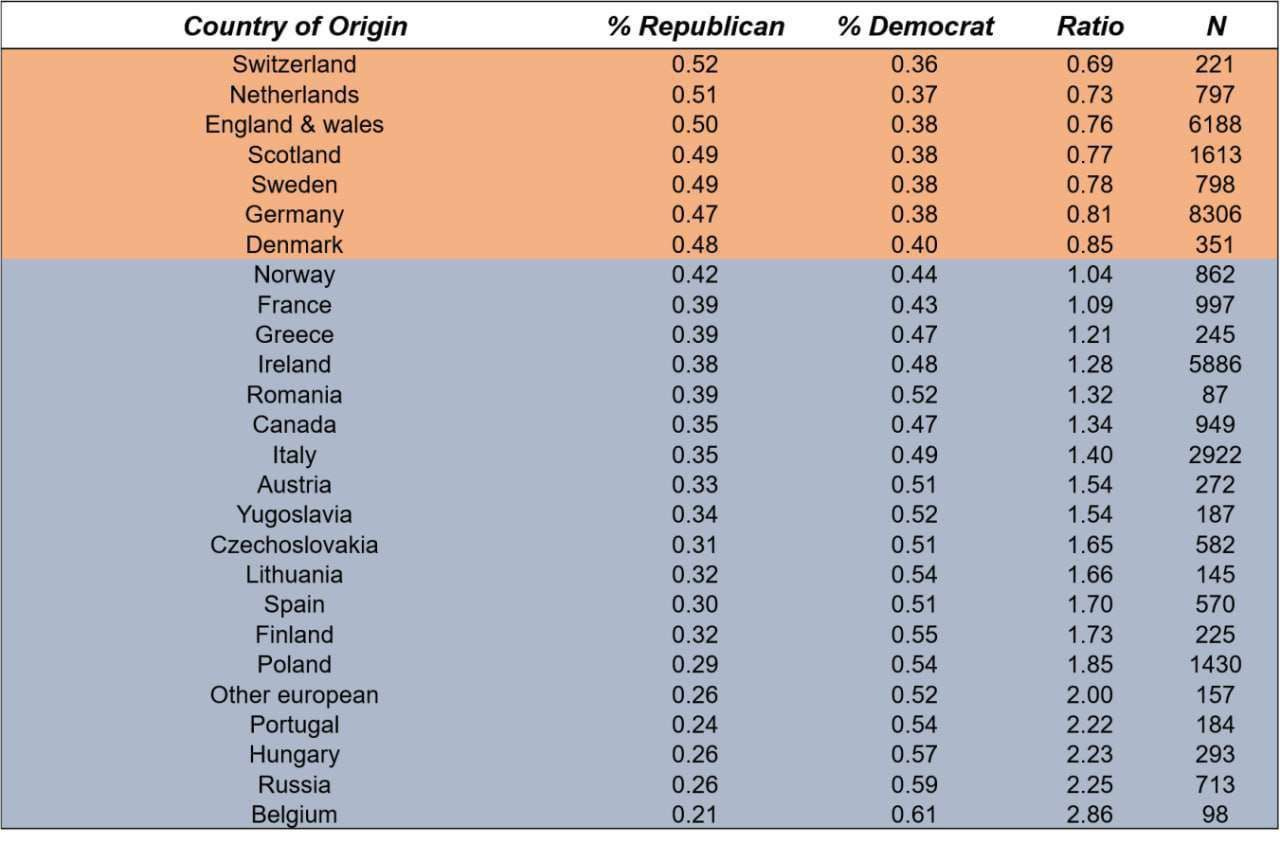

In this article I decided to look deeply into the Russian diaspora in Canada, more particularly to study their political views. For some weird reason people believe that Russians tend to lean left, and they support this assumption by the table of political orientation broken down by country of origin that you can see below. Obviously this is not true of my experience and the experience of Russians I talked with, but I didn’t have strong empirical data to justify this until now.

The problem with the table above, is that there aren’t that many ethnic Russians in the, while the table shows that there are a lot of people who have originated from Russia. That is because of immigrants who come from Russia tend to be Jewish, and thus skew the distribution towards the Democratic side. That is why such assessments should not be based solely on country of origin; ancestry must be taken into account, which is what this article will do.

For this article I am going to rely on research drawn from a large “multigenerational survey, conducted using the Léger Online Panel, and several focus groups with individuals living in the Greater Toronto Area and Alberta, conducted with Pivotal Research.” The survey includes, the general Canadian population, older Russians who have migrated to Canada in the 1980s and 1990s and their descendants mixed with the descendants of Russians who have migrated in the early XXth century like the descendants of Doukhobors or the descendants of White Russian emigrees like Michael Ignatieff, though majority of the questioned are going to be the descendants of those migrated between 1980s and early 2000s.

Some unique insights and conclusions, including in what respects Russians differ from other Europeans are going to be behind the paywall.

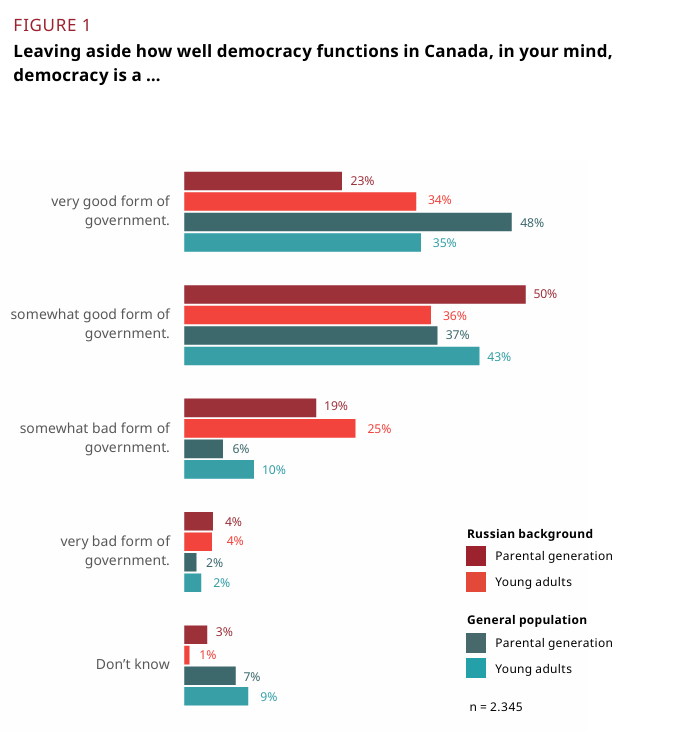

Russian-Canadian attitudes towards democracy:

Russians appear to be intrinsically more authoritarian than the Canadian average and not as enthusiastic about democracy as is the general population. Part of it has to do with the fact that Russians are somewhat withdrawn from politics:

Our survey finds significantly higher rates of abstention among respondents with a (Soviet) Russian background compared to their age peers in the general population.

With regards to the participation in the Russian elections among Canadians, the data is the following:

About one-third of Russian respondents aged 35 and older report that they usually participate in Russian state elections, another third do not, while the remaining respondents are either not eligible or chose not to respond. As one explanation for their abstention, focus group participants referred to their belief that elections in Russia are ‘rigged’. Among the younger respondents, half are ineligible to vote, and only a very small fraction of the rest participates in Russian elections.

Among those who have voted, slightly over 50% have casted their ballot for Pvtin. Although interestingly enough, 25-31% of Canadian Russians have voted for the moderate Dovankov, while just 3.9% of Russians living in Russia voted for him.

In other countries like Czechia, Serbia, Spain, Kazakhstan, Netherlands and Armenia Dovankov received about 2/3 of the Russian vote or more and Putin under or around a quarter, while in the Baltic states Pvtin got about 2/3 to 3/4 of the Russian vote.

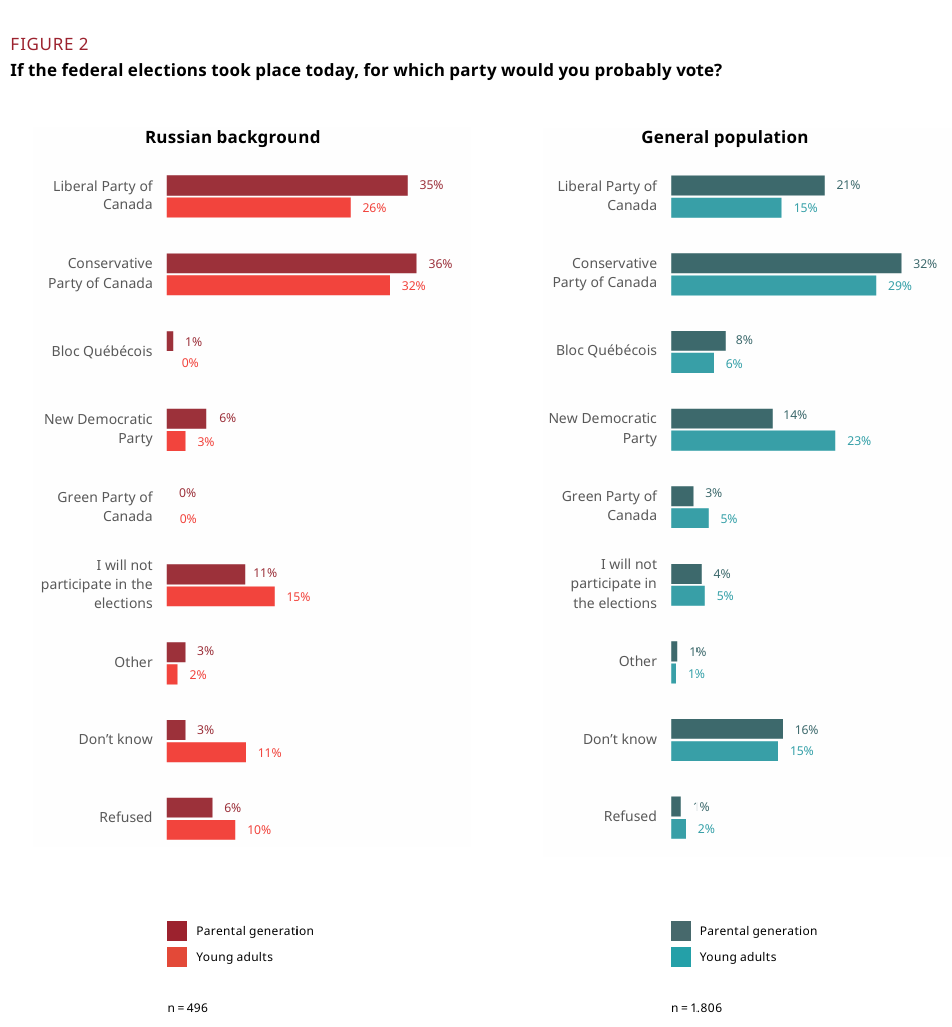

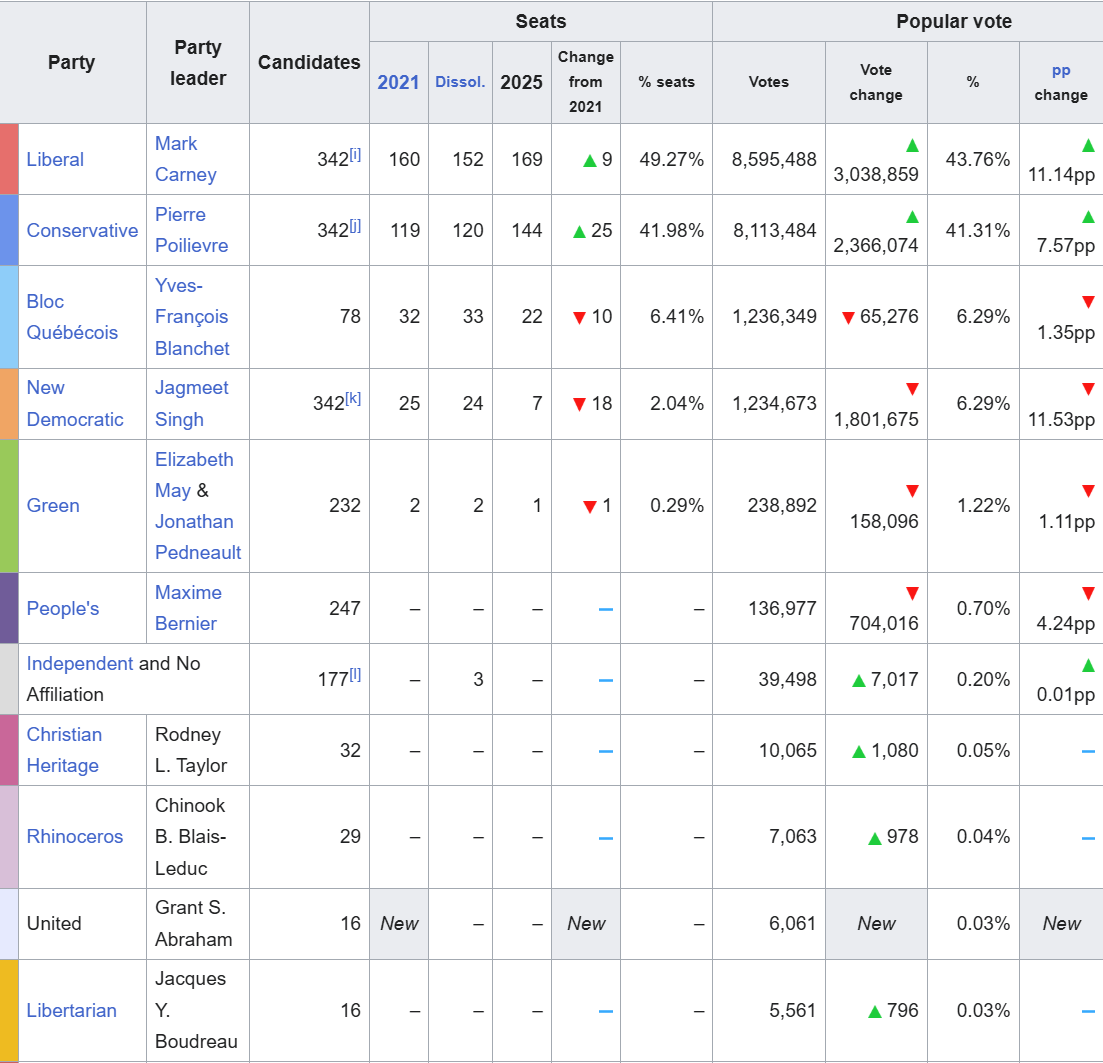

Who do Russians vote for in the Canadian elections?

Russians are generally divided between Liberals and Conservatives and do not consider the Quebecois Nationalist party, along with the left-wing Green Party of Canada and the left wing New Democratic Party.

Regular Canadians on the other hand, are much more politically diverse, but slightly less Conservative. Young Russians, overall, are less supportive of the Liberals than their parents, and a clear majority of them back the Conservatives. The same is also true of the general population, but largely because they have switched to the left wing New Democratic Party instead. In other words, Russians are a moderate demographic, with one exception…

The exception is that Russians have likely voted for the right wing populist People’s Party three times the rate of the general population which is hidden under “Other” category. I myself have voted for them in the 2025 election cycle and I know another Russian person who has voted for them as well.

Although, the Russians may have also voted for the independents disproportionately. We will never know, but I have a strong suspicion that they have backed the People’s Party, partially due to their pro-Russian stance in the Ukraine war.

The biggest takeaway from this is that Russians are not properly civically and politically engaged in comparison to their Canadian counterparts. About a third of young Russians are totally withdrawn from the political life, compared to about 10% of the general population. Their parents were about 20% withdrawn and the speculations as to why this may be the case are going to be put behind the paywall.

Evidence of Russian ethnocentrism:

The parental generation with a (Soviet) Russian background is more likely to have made donations to Russian organizations in Canada or in Russia itself. Yet remarkably, unlike the national reference population, this group is not involved to any meaningful extent in aiding Ukrainian refugees. The few who have become involved in this area cite the shared language as a reason for their engagement. A young woman from Toronto said she was motivated to support Ukrainian refugees ‘because a lot of them do also speak Russian’ (female, 19 years, Ontario)

Russian-Canadian views on the Ukraine war:

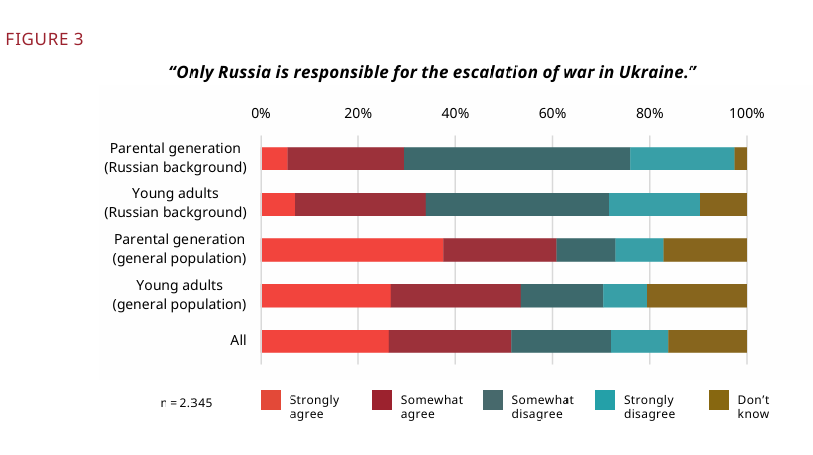

Less than 5% of Russian young adults and parental generation Russians believes that Russia is solely responsible for the Ukraine war, compared to about 25% of the general population if we measure by strongly agree. When it comes to disagreeing with the statement, about 70% and 60% of parental and young Russians disagree respectively, compared to just 25% of the general public.

Still, this doesn’t measure prescriptive attitudes, it measures descriptive attitudes, since I am very certain that a majority of international relations scholars would also dispute the fact that only Russia is responsible for the Ukraine war.

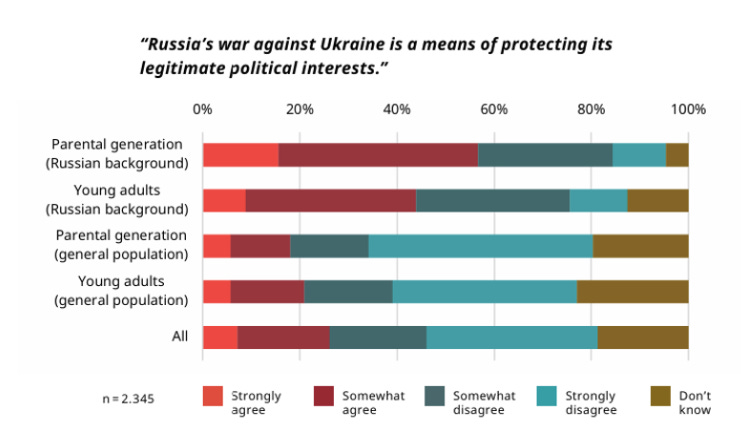

The second question is more prescriptive: it asks whether the war in Ukraine represents Russia’s attempt to defend its legitimate interests. About 20% of the Canadian public agree and 60% disagree, compared with roughly 45% agreement among young Russian adults and nearly 60% among the parental generation.

Another interesting thing is that the general population is more radical in strongly rejecting this assertion at the rate of almost 50% while both Russian generations reject it radically at only 10%.

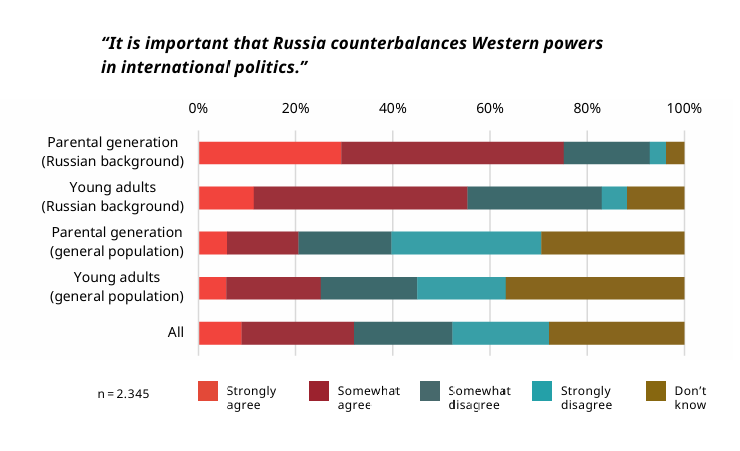

Finally there’s the question that directly measures either Russian revanchism or adherence to multipolarity. Older Russians are remarkably hawkish for Russia, while younger Russians are not so much. Majority of the general population doesn’t care and among those who do, the atitutdes are almost evenly split among the younger generation. To quote from the study:

Across all three questions, there is a tendency for male respondents, young er people, and those who are better off to have views similar to those propagated by the Kremlin.

Russian-Canadian views on economics:

Respondents with a (Soviet) Russian background are less likely to criticize socio-economic inequality. To a greater extent than the general population, they attribute poverty to insufficient personal commitment, possibly speaking to their own reliance on hard work rather than family heritage for upward mobility

When asked for their opinion on the statement ‘Poverty is primarily the result of a lack of personal commitment’, on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree) individuals with a (Soviet) Russian background scored an average of more than 6 across both generations. In contrast, the general population scored an average of below 5.

This is consistent with the fact that Russians are naturally fiscally conservativeas there is basically no intergenerational change in atitutdes.

Attitudes towards immigration to Canada:

Respondents with a (Soviet) Russian background are more likely to see newcomers as a threat to the Canadian way of life.

Unfortunately no statistic was cited, although in my experience of talking with the Russian community, many are skeptical of non-White immigration into Canada, but that may be because I am not surrounded by Russian shitlibs.

Attitudes towards “Indigenous” (Siberian) Canadians

For respondents with a (Soviet) Russian background, recognition of the suffering of Indigenous people is not something they consider essential to being part of Canadian society. This contrasts with the broad consensus on this issue among respondents in the national reference population

Unfortunately no statistics were shown this time around. I can confirm that we hate the special status and privileges that these people get over the rest of Canadians.

Attitudes towards feminine men:

We asked our respondents whether men should have the freedom to wear dresses, makeup, and nail polish. On a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree), first-generation (Soviet) Russian migrants scored an average of just over 3, compared to an average of nearly 7 among other Canadians aged 35 and older. The younger generation with a (Soviet) Russian background scored an average of slightly over 5, whereas their age peers in the general Canadian population scored over 7.

This is what shitlibs would call “toxic masculinity”.

Attitudes towards non-binaries and transgenders:

More than half of respondents from the national reference population state that they would be willing to accept such a person — on a 10-point scale they score upwards of 7 on average. The reverse holds for people with a Russian background, where more than two-thirds of respondents aged 35 and older score 3 or lower. Younger respondents with a Russian background score 4 on average

Pretty transphobic and queerphobic.

Attitudes towards the Holocaust:

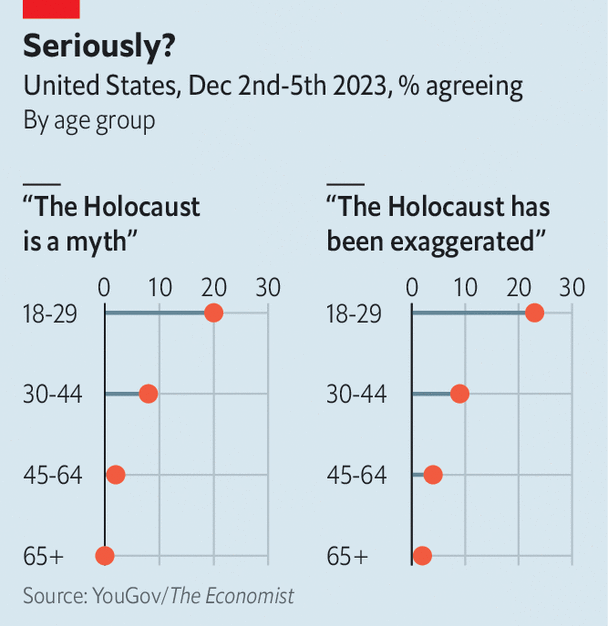

Our survey shows the extent to which young respondents with a Russian background cannot relate to that event. Indeed, when asked how many people perished, nearly a quarter indicate that it was either a ‘small fraction’ or that ‘nobody really knows’, as opposed to just 8 per cent of first-generation migrants with a (Soviet) Russian background and about 15 per cent of the Canadian reference population with similar views.

While older generation Russian migrants are better versed in the Holocaust than Canadians due to Soviet education, it does appear that young Russians are far more likely to embrace Holocaust denial, but it is consistent with American cultural trends, and thus signifies a case of Russian assimilation into the popular online culture, and so Russians are probably not significantly more likely to deny the Holocaust than other young Canadians.

Associations with the Soviet Union:

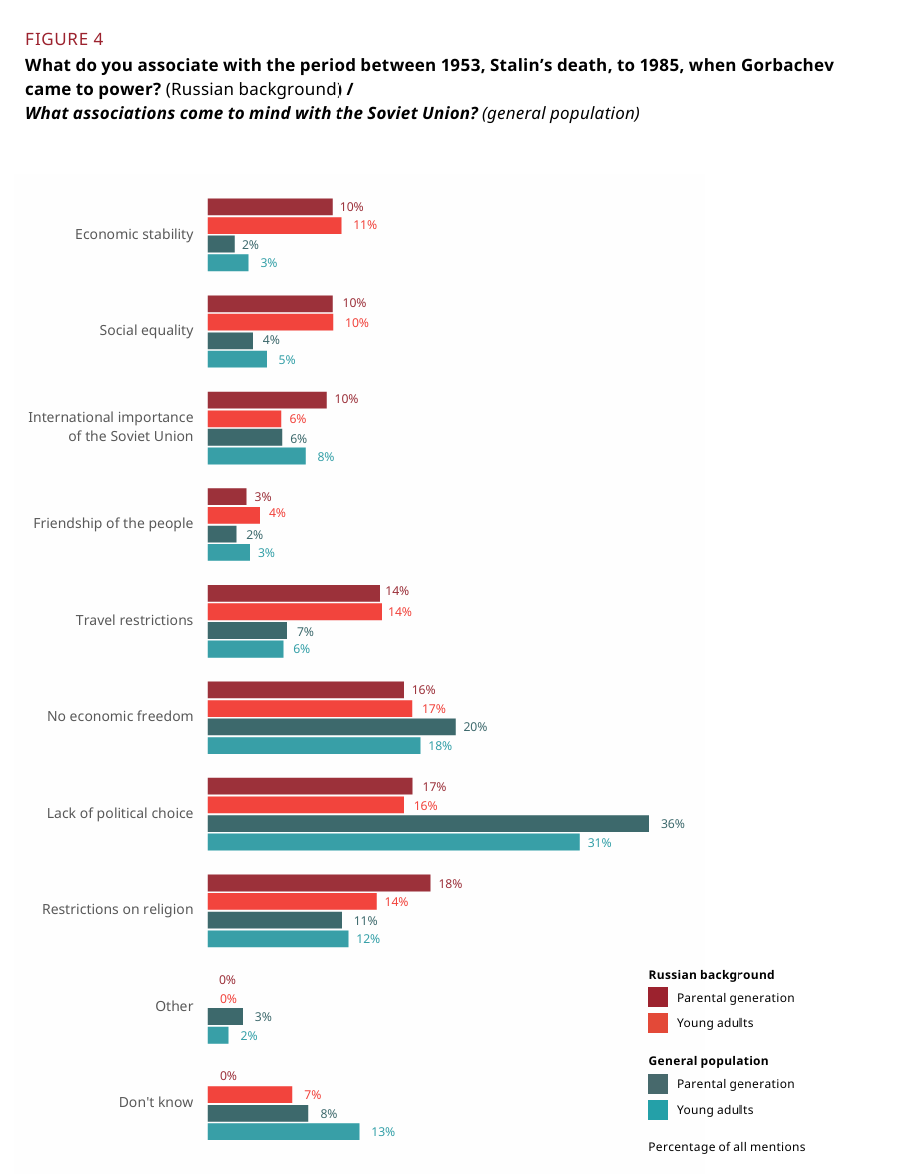

About 35% of Russians appear to be sympathetic for the Soviet Union, the vast majority is not.

Unlike their peers in Russia, even Canadians who were socialized in Soviet Russia tend not to be nostalgic about the Soviet Union. As our research shows, ‘friendship of the peoples’, a key positive association with the Soviet era in Russian society, holds little significance for Russian migrants in Canada.

Russian Canadians also place no great value on other qualities of ten attributed by Russians in Russia to that period of history: economic stability and social justice. The lack of positive associations is even more pronounced among other Canadians, who emphasize the lack of political choice and economic freedoms.

This is not surprising considering a lot of Russians came during or after the fall of the Soviet Union, and thus like other immigrants from socialist states they tend to be distrusting of socialism which they associate with misery, poverty and lack of freedoms. As you remember, Russians are also more fiscally Conservative than the Canadian average. The article continues:

Speaking to the general lack of emotion that history arouses in them, respondents with a (Soviet) Russian background are also unlikely to feel anger when Canadians speak negatively about Soviet-Russian history. Fewer than 10 per cent of older respondents and an even smaller share of younger respondents say they would definitely feel angry.

Russian Identity:

Traditions:

Families with a (Soviet) Russian background in Canada consider traditions from their country of origin important. More than 80 per cent of older respondents and over 50 per cent of younger respondents say that such traditions are somewhat or very important. This mirrors the views of other Canadians with a migratory background on their respective traditions. Several focus group participants mention hybrid cultural practices:

‘ We do two Christmases in my household, so one in December and then one later in January, like Orthodox Christmas.’ female, 25, Alberta

Attendance of cultural, sports or youth events with co-nationals is an indicator of connectedness within the (Soviet) Russian community. Almost 40 per cent of the parental generation with a (Soviet) Russian background say they participate at least occasionally in such events — a value that is only margin ally higher among other ethnic minorities in Canada. Among the younger generation, about one-third attend these events occasionally, irrespective of their migration background.

Links to Russia:

Canadians with a (Soviet) Russian background are largely disconnected from Russia. Younger individuals in particular have either cut ties or never had them to begin with. They are far less likely than young people with other migratory backgrounds to have immediate family members or friends in the ancestral homeland (under 10 per cent). Among the older respondents, approximately one-third have immediate family members or friends in their country of origin, similar to people with other migratory backgrounds. A similar share in both generations, about one-third, still has connections to more distant relatives in Russia,

This trend sets Canadians with a (Soviet) Russian background apart from Canada’s non-Russian migrant population. Only a small fraction of people with a (Soviet) Russian background are in regular contact with family members in Russia — slightly over 20 per cent of the older generation and less than 10 per cent of the younger generation. In contrast, nearly three-quarters of other migrant respondents maintain such regular communication with family members in their country of origin. Travel to Russia is also rare. More than 80 per cent of the young adults with a Russian background mention that they have not visited Russia in the last five years. The same is true for half of the older respondents.

This is very strange if we compare them with other diaspora groups. The point about travel may be overexaggerated because of the sanctions as there are no direct flights between Canada and Russia.

Assimilation into Canada:

For younger respondents with a (Soviet) Russian background, Canadian traditions are more important than Russian ones: Nearly 90 per cent state that they are somewhat or very important, similar to the share of the overall Canadian population that values Canadian traditions. They also matter to the parental generation with a Russian background: Around 70 per cent of these respondents indicate that they consider them somewhat or very important.

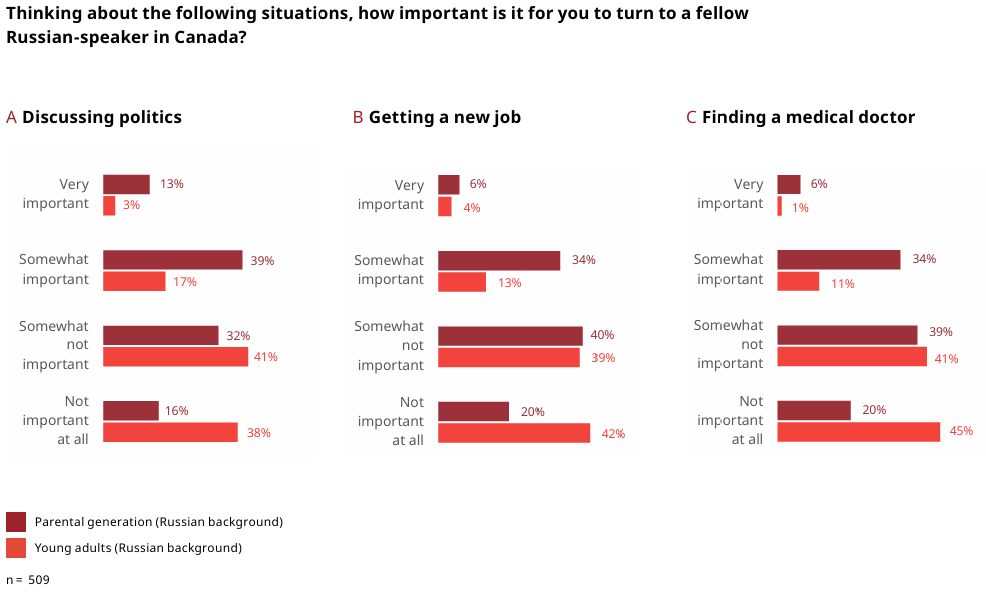

The biggest sign of integration and generational change is that young Russians are not relying on the Russian community for pretty much anything. They feel as integrated Canadians which is again, very different from other migrant groups who are highly nepotistic.

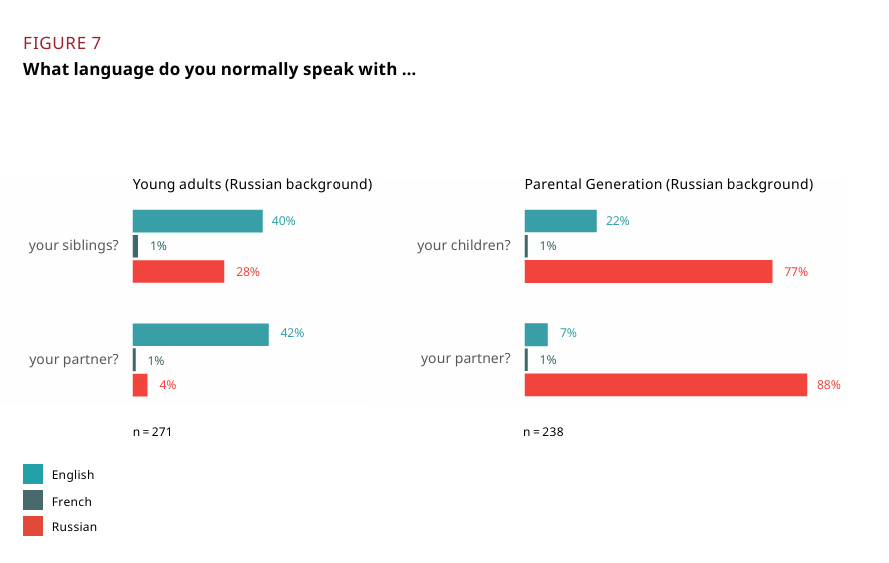

Same thing likely can be observed with language as Russians appear to be marrying Canadians and switching to English which is very reminiscent of the assimilation patterns of every other European group that comes to Canada or the US.

To calculate the approximate rate of intermarriage I looked at the 2021 Canadian census data. It shows that 548,000 Canadians report at least partial Russian ancestry, while 116,000 of Canadians are fully ethnically Russian. Dividing 116,000 by the remaining 431,000 yields roughly 0.27, which can serve as a proxy for the share of Russians marrying other Russians. For comparison, here is the ratio of single-ancestry to mixed-ancestry groups across other communities:

Koreans: 7.3

Chinese: 4.02

Indians: 2.63

Vietnamese: 2.35

French Canadians: 1.86

Greeks: 1.06

Italians: 0.77

French: 0.61

Dutch: 0.39

English: 0.33

Poles: 0.32

Ukrainians: 0.28

Russians: 0.27

Spanish: 0.26

Germans: 0.20

Americans: 0.16

Irish: 0.15

Scotts: 0.14

Norwegians: 0.1

Welsh: 0.08

Swedish: 0.07

TLDR: The Russians are assimilating and integrating at an exceptionally fast rate but paradoxically they retain their political but not social ties to Russia and are also partially observing their cultural traditions even if they don’t speak the language or are married to non-Russian Canadians. That being said, they are more culturally Canadian than they are Russian. Politically they are more Conservative than average, are significantly less political than average, are slightly more predisposed to authoritarianism and are not temperamentally predisposed to hardline leftism. Aka a good population for a potential right wing authoritarian regime.