The Economic Case for Immigration Is Dead

Challenging Economic Orthodoxy: A Post-Keynesian Critique of Immigration Arguments

Introduction:

One of the most pressing issues of our day is immigration. Since the 1960’s millions of non-European foreigners have flooded into European homelands. The consequences of this have stirred up mass social unrest and opposition to migration. With the success of the third Trump campaign, the growth of the Reform party in the UK, and also with recent the success of the AFD in Germany it is obvious the people do not want immigration. However, many on the opposite side of the political spectrum have pushed back against this hostility. Defenders of replacement migration argue that immigration is a net positive, and most of their arguments are rooted in economics. This is to be suspected of libertarians, but the left has also embraced these arguments. The economic arguments in favor of immigration rely on the typical orthodox thinking around our economy (and so do the economic arguments against immigration.) But, what if the orthodoxy is wrong? What are the implications of immigration when placed under a heterodox (specifically post-keynesian) analysis of the labor market? In this paper I will demonstrate how the traditional immigration debate is severely displaced due to its reliance on orthodox economic thinking. Likewise, the economic arguments in favor of immigration are extremely short-sighted. Due to the rise of technological advances that have led many firms and sectors automazing, the reliance on human labor is falling. Not only in this article will argue the arguments in favor of immigration are wrong, I will argue they are obsolete.

PS: The voice-over misses 15% of the text; one section near the end and the conclusion.

Common Arguments:

Before I present my argument against immigration, orthodox economic theory as a whole, it is important to address some of the main arguments used in favor of immigration. These are:

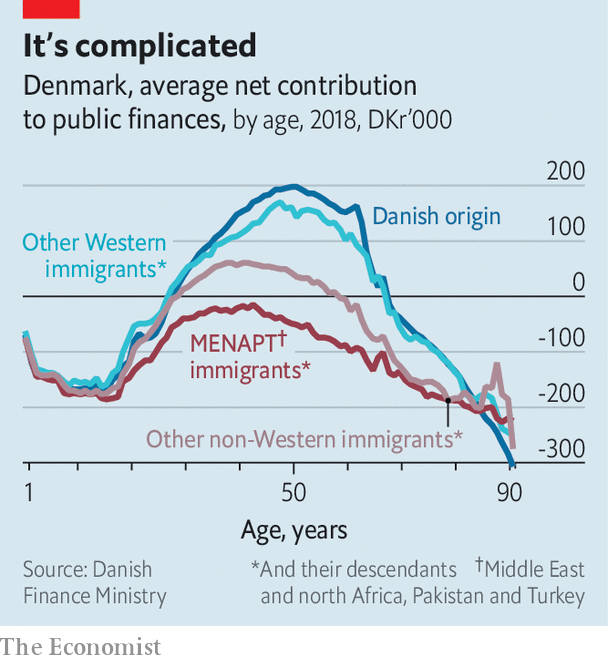

“How will we pay for social security in an aging population without immigrants? They give so much revenue!”

“Immigrants contribute significantly to the economy and make us all richer!”

“We get the best and brightest from other countries which helps us innovate more and compete globally!”

To address the first argument, I already get to show what type of economic tradition I adhere to. First thing that needs to be said is taxes don’t fund government spending, and the government spends before they tax. With this being said, due to the fact America’s currency is fiat, and monetarily sovereign, it has a monopoly on its own currency. It can not “run out” of money. With this fact, the United States is not financially limited in money creation. Yes, increases of the government created money does not cause inflation. Empirically, we know the correlation between m2 and the CPI is at most incredibly weak and for the most insignificant. Vague (2016) looked at 47 different countries, from 1960-2016 and found no correlation between the money supply and inflation rate:

“Based on our examination of countries that together constitute 91 percent of world GDP, we suggest that high inflation has infrequently followed rapid money supply growth, and in contrast to this, high inflation has occurred often when it has not been preceded by rapid money supply growth.”

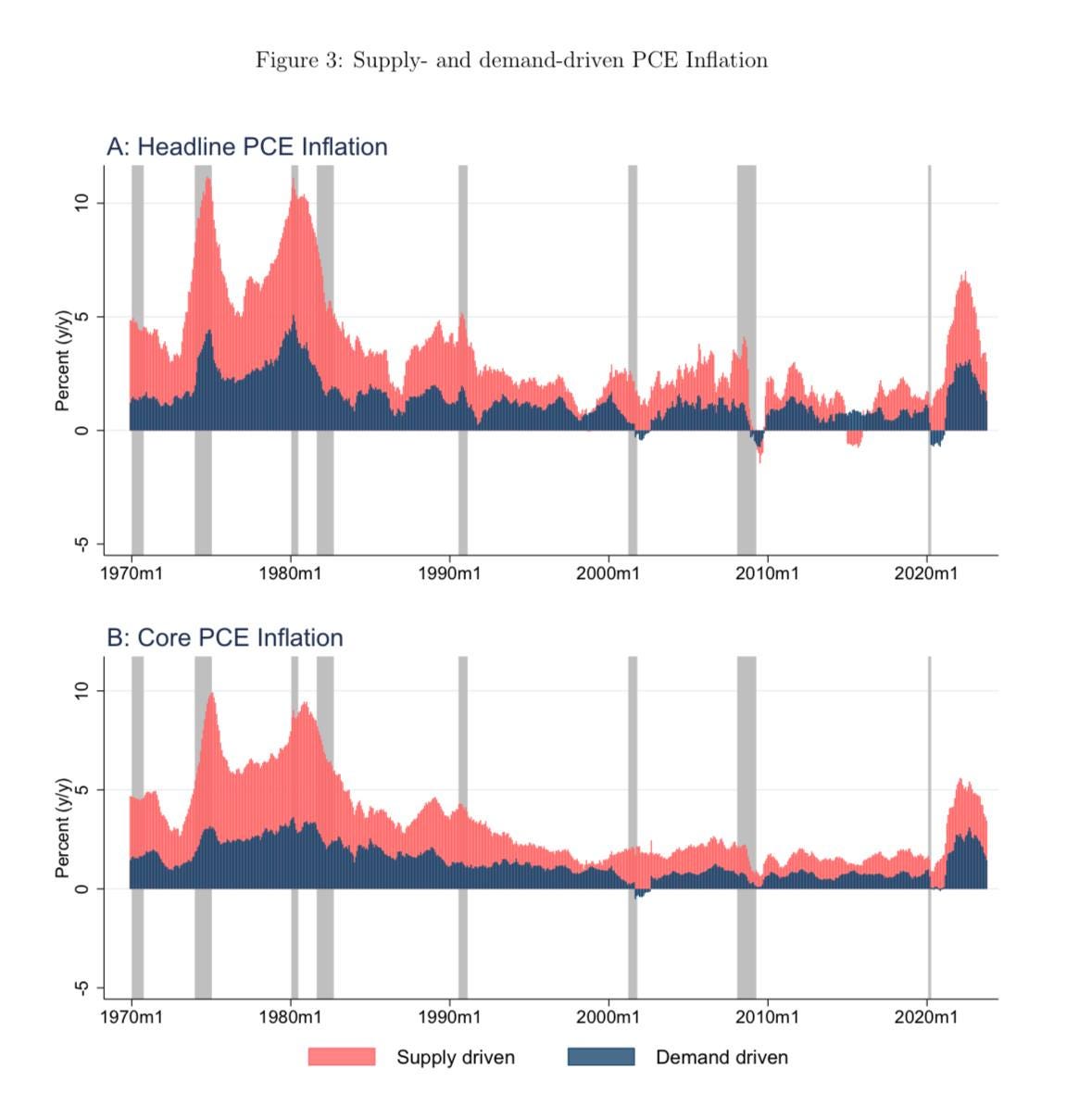

Grauwe&Polan (2005) examined 160 countries over a 30 year period and found a correlation between money supply growth and inflation, but only restricted to high inflation countries. When examining low inflation countries (mostly Western developed nations) they state “Our second finding is that this strong link between inflation and money growth is almost wholly due to the presence of high-inflation or hyperinflation countries in the sample. The relation between inflation and money growth for low-inflation countries (on average less than 10% per year over 30 years) is weak, if not absent” Inflation in the United States has almost never been because of overspending. Shapiro (2024) found the vast majority of inflationary periods in the United States have been supply sided, mostly shocks in the oil supply, not demand sided overspending.

It can be the case the United States can overspend supply, they are constrained by real resources. However, it can not run out of money, and fears of deficit financed spending causing inflation are not empirically backed. So in regards to the social security debate. The US can not run out of money to finance social security. As Eisner (1998) explains the “fundamental misconception, that payment of benefits somehow depends upon the OASDI (Old Age and Survivors and Disability Insurance) trust funds. The trust funds are merely accounting entities.' Our payroll taxes or "contributions" go directly to the United States Treasury. Our benefit checks come from the Treasury…Social Security payments are an obligation under law of the U.S. government. Our government and its Treasury will not, indeed cannot, go bankrupt.”

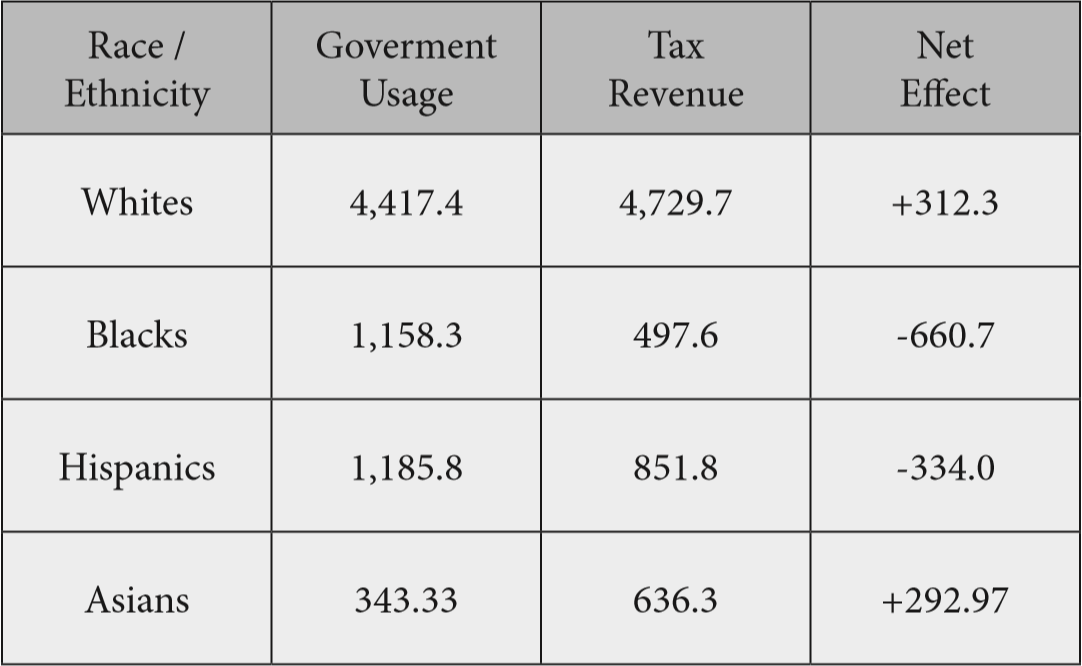

The trust funds are just accounting identities! It doesn’t matter whether we run a positive or negative balance. We will never run out of money. The left’s persistence that we need immigrants to pay for social security uses the exact same logic the right uses to justify cutting social security. The continuation of this paradigm has dire consequences. But even if remain inside the paradigm of “social security will go bankrupt” , why is the solution simply to bring in more tax payers? This solution doesn’t even make sense as immigrants pay less tax revenue than natives as they are lower income, and what about their descendants? Who pays for them? This weak justification just gives ground for an endless stream of brown people coming into the country.

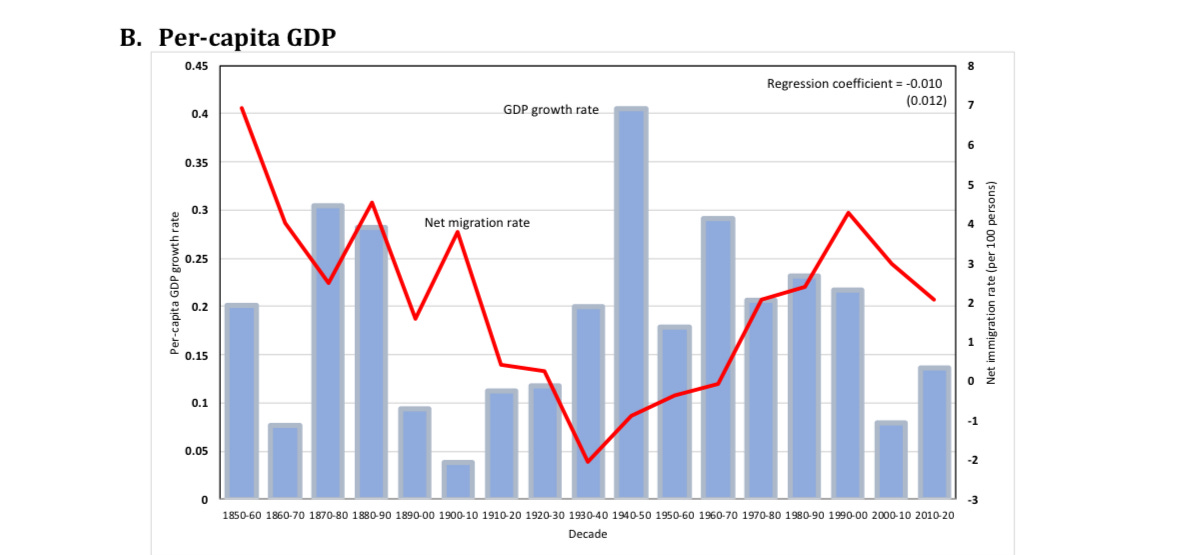

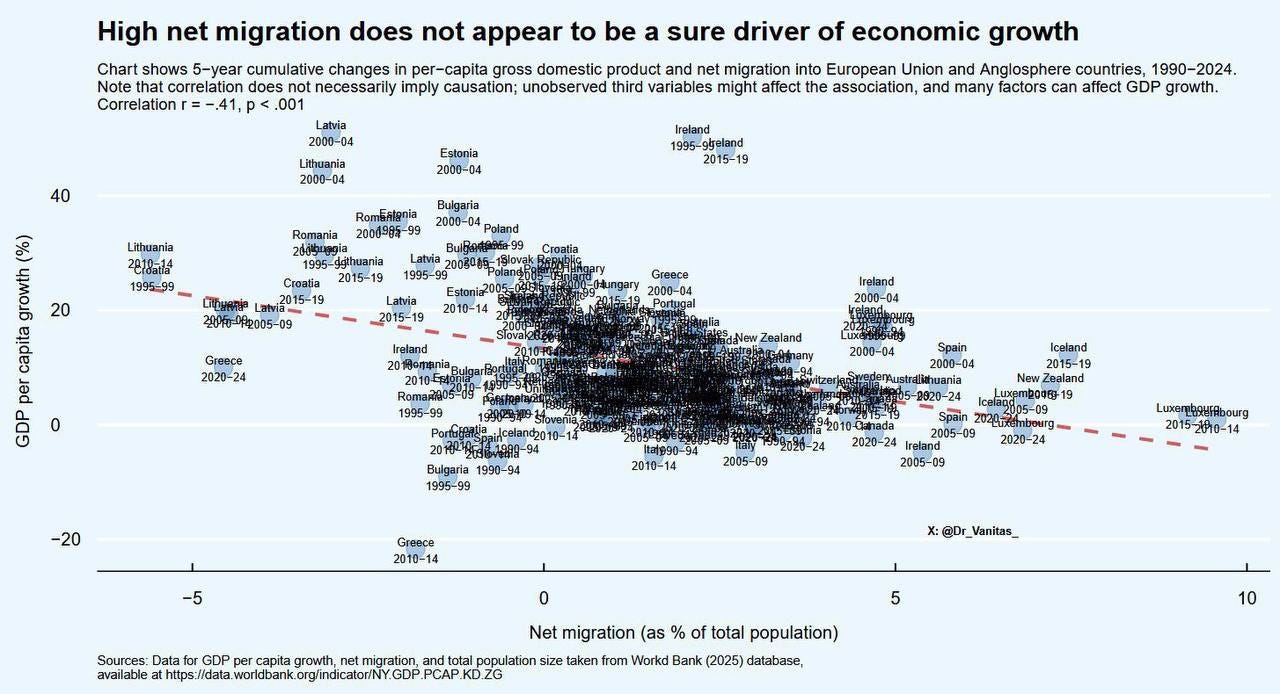

Back to the second point, it is true immigrants make the economy larger in a literal sense. Having people in the economy does not necessarily make it wealthier in a real sense. Take India for example. India has the 4th largest nominal GDP in the world, however its GDP per capita is 119th in the world. (IMF 2022) The reason India’s economy is so large is because of how many people it has, which is over a billion. The real wealth of India, i.e. GDP per person is not so great. So on the question of immigration, we are interested in the causal relationship between immigration and GDP per capita. Borjas 2019 gives us data to answer this question he finds immigration is actually very so slightly negatively correlated with GDP per capita.

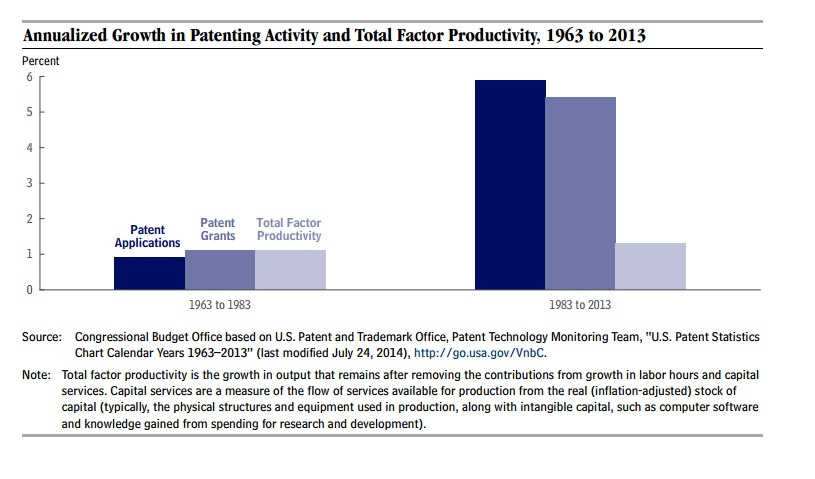

Lastly, the argument revolving around innovation is a compelling one. Immigration does seem to increase innovation. Bernstein et al 2022 found exactly this. The first thing that needs to be stated about this study is I’m not particularly convinced patents are a good metric for innovation (Bruenig 2019).

This aside, the study states that “in surveys of Silicon Valley, 82% of Chinese and Indian immigrant scientists and engineers report exchanging technical information with their respective nations.” So the geopolitical advantage America should be getting from the increase of innovation doesn’t happen because the vast majority of Indian and Chinese immigrants share information with the very people we are competing with. How is this a good argument?

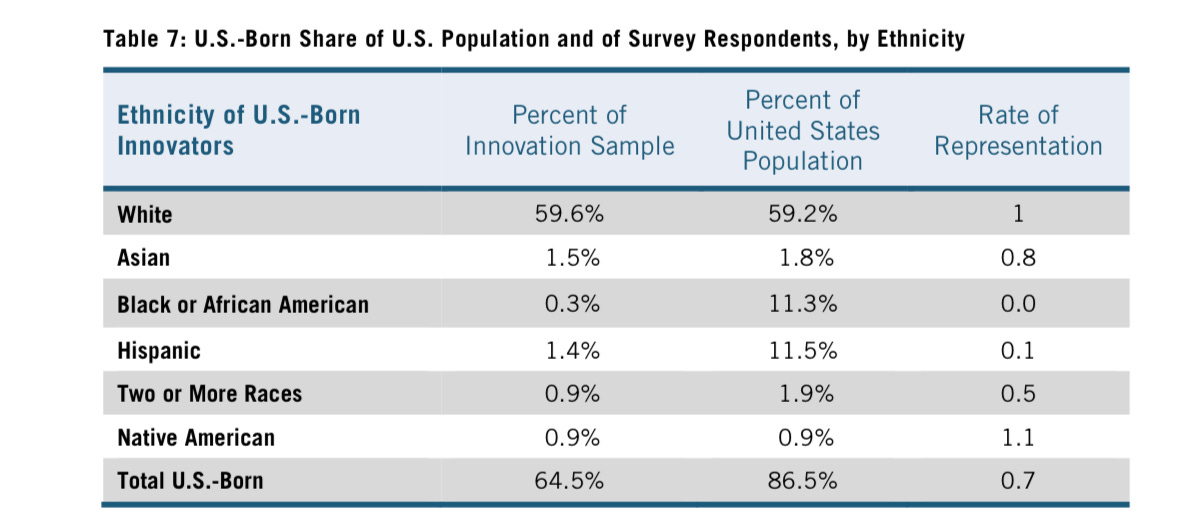

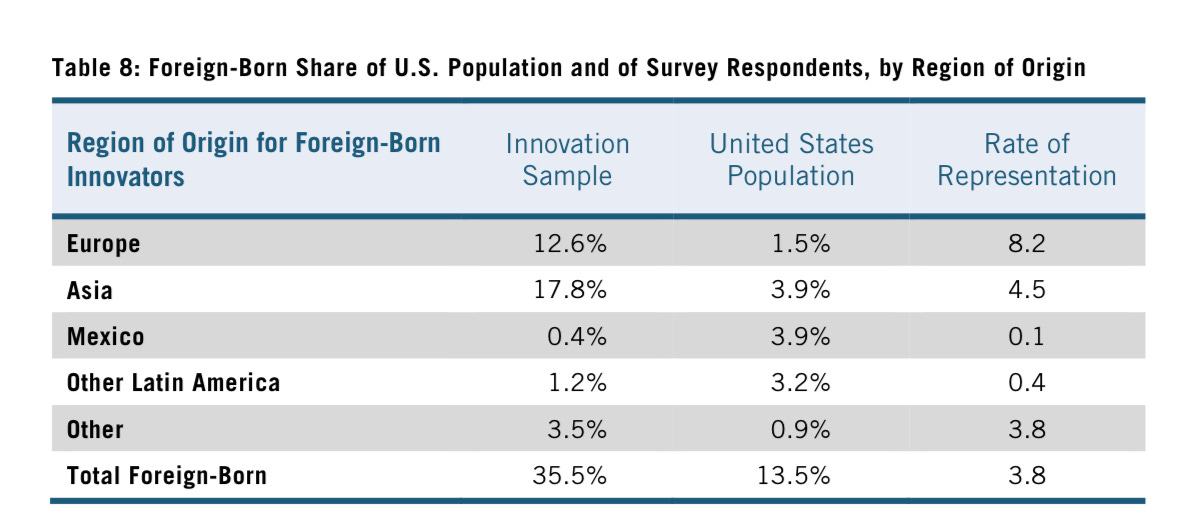

Likewise, there is no country called “Immigratia.” The immigrants that are coming here come from vastly different countries, and the people that are born here differ significantly when it comes to contributions to innovation. Thus it is important to look and see at the specific groups who are doing the innovation. From Nasher (2016) we find that Whites, both native born and immigrants are vastly overrepresented in innovation. Asians, Hispanics, and Blacks are vastly underrepresented. When looking at the ethnicity of foreign born innovators, Europeans are the most innovative, overrepresented by a factor of 8.2. Asians are also overrepresented, and Mexicans and other Latin Americans are vastly underrepresented.

The lack of success amongst American born non-Whites, and the large success of foreign born Europeans and Asians explains the over representation of immigrants in innovation. Likewise, the advantage of Asian innovation goes away after the 1st generation. The problem is for the pro-immigration argument, the vast majority of immigrants who have come into America in the past 60 years have predominantly been Hispanic, who are not at all great innovators. If we were to create an immigration system that is solely based upon innovation, then we should go back to the highly restrictive national quota system of the 20th century. Not at all a “pro-immigrant” system.

Wages:

Noah Smith in his article on why immigration doesn’t cause wages to fall, gives a nice summary on what the debate typically looks like. “Basically, most people think of immigration as an increase in labor supply. Labor supply is the number of people willing to work at a given wage. So, more people, more workers for any given wage. As a result of the labor supply increase, wages go down.” He then goes on to say “takes labor. Haircuts take labor. Doctor visits take labor. Building new apartments takes labor. And so on. Even if the immigrants don’t start spending their money on day 1, businesses can see the immigration wave coming and they know there will be increased demand for their products. So they hire more people. To hire more people they have to…raise wages. So immigration increases labor demand as well as labor supply.”

This is how the debates typically go. Immigration increases supply, but they also increase demand therefore having a null or maybe even positive net effect on wages (and then both sides just throw data at each other.)

But, are prices actually determined by supply and demand? Nope!

In fact, prices can’t work that way. If prices were flexible, and determined solely by the demand for the supply of goods, this would cause extreme bankruptcy because firms would engage in “price wars” which would destroy profitability. Likewise, this type of pricing would cause extreme uncertainty as any “shift” in demand would cause a change in price. The majority of prices are administrative, which is simply that these are prices that are calculated using the average total cost plus a profit markup. Fabinie et al (2006) presents data from the Eurozone and finds a whopping 54% of firms use mark-up pricing. “In the euro area, more than half of the firms fix their price as a markup (fixed or variable) over costs. At the two extremes we find Germany (73 percent) and France (40 percent).” This isn’t to say demand never plays a role in pricing, but the conventional way prices are set just doesn’t happen. Another blow to orthodox pricing theory is the stability of prices of the decades. As Lee (2013) notes “Starting with prices, since the 1930s, it has been known that price stability dominate the industrial, wholesale, and retail areas of the American economy. The 40-50 studies in the past fifteen years by Alan Binder and others which cover developed countries around the world further support the existence of price stability. One basis for its existence is the administered cost-plus pricing mechanism (used by virtually all business enterprises to set the prices) which neutralizes the impact of changing sales on costs hence prices. So price stability and its underlying pricing mechanism are systemic features of developed economies such as the American economy resulting in a disjuncture between price and quantity.”

A much damning problem for neo-classical economics is that the “Law of Demand” is false in the way they conceive it. The reason is because the demand curve can rise, when prices also rise. This is because when you add one more commodity into the supply and demand chart, it can bend however way it wants. As Steve Keen notes in his brilliant “Debunking Economics” “According to economic theory, each consumer attempts to get the highest level of satisfaction he can from his income, and he does this by picking the combination of commodities he can afford which gives him the greatest personal pleasure…Economists were therefore unable to prove their assertion, unless they could somehow show that altering the distribution of income did not alter social welfare. They worked out that two conditions were necessary for this to be true: (a) that all people have to have the same tastes; (b) that each person’s tastes remain the same as his income changes…When conditions (a) and (b) are violated, as they must be in the real world, then several important concepts which are important to economists collapse. The key casualty here is the vision of demand for any product falling as its price rises. Economists can prove that ‘the demand curve slopes downward in price’ for a single individual and a single commodity. But in a society consisting of many different individuals with many different commodities, the ‘market demand curve’ can have any shape at all – so that sometimes demand will rise as a commodity’s price rises, contradicting the ‘Law of Demand.’”

Putting aside the failures of neo-classical orthodoxy, even if we presuppose the supply-demand model is correct for commodities, it can and is still incorrect when it comes to labor. The reason this is the case is because 1. the supply for labor can be “back wards bending” and 2. monopsony (something Smith notes at the end of his article).

Once again, turning to Keen “Neoclassical economists blithely draw upward-sloping individual and aggregate labor supply curves, but in fact it is quite easy to derive individual labor supply curves that slope downwards –meaning that workers supply less labor as the wage rises. The logic is easy to follow: a higher wage rate means that the same total wage income can be earned by working fewer hours. This can result in an individual labor supply curve that has a ‘perverse’ shape: less labor is supplied as the wage rises.” Now you might go “what about substitution effects?” This is true of commodities, where you can just add or subtract to a consumer’s income, you can’t do that for labor since there are a fixed amount of hours in a day.

Since orthodox supply and demand models can’t depict the labor market accurately, what does? As Marc Lavoie points out, it’s mostly vibes. “The market for labour has to deal with labourers, which 'bring with them not only their labour-power but also their past history and norms of justice in the workplace… the notions of fairness and justice often permeate the determination of the prices of things, in particular the prices of manufactured goods. The question of justice and of norms is even more fundamental in the so-called market for labour.” (Foundations of Post Keynesian Economics 1992)

Another point is monopsony or large firm power OR weak labor power. Since it is necessarily the case labor is dependent on capital, capital will always necessarily have more power over labor. This can be counteracted by government policy or high union density, but capital certainly has the power to just keep wages low. And there is good reason to believe this is currently happening. Take for example the minimum wage debate. Orthodox theory would tell you that the minimum wage would drive a wedge between the demand for labor and the supply, thus causing unemployment. However the vast majority of empirical evidence suggests this is not the case. (Dube 2019) What explains this is firms are pushing wages below “market rate” and thus when a law is passed forcing wages up, they aren’t affected that much (besides eating some of the increase of labor costs into lower profits see Reich 2024.) Likewise, unions are crucial for wages and worker wellbeing, with unions playing a causal in higher wages (Banerjee et al. 2021) and the decrease of unionization being the primary reason for labor’s share of income falling (Stansbury&Summers 2020).

So with all of this being said, what does this have to do with immigration? Well, if wages (like most commodities) aren’t set by supply and demand, and labor power plays a large role in determining wages, firms are obviously going to have a preference for immigrants who have significantly less bargaining power and are significantly cheaper than native born Americans. Native born Americans then have to “compete” with immigrants, thus creating a race to the bottom. Now putting this direct influence aside, immigrants decrease wages in a much more indirect way, albeit a way that arguably has a larger impact on wages. It is a well replicated fact that diversity negatively correlates with social cohesion (Dinesen et al. 2020). And this negative correlation is larger as the proximity to diversity is closer to individuals (see figure 2 of Dinesen et al also see Dinesen&Sønderskovb 2015).

With this being said, immigration increases diversity into the workforce, thus workers are going to trust each other less and thus interact. This will naturally cause workers to be less unionized (Benos&Kammas 2023). A study released by the CATO institute found that almost 30% of the fall in union density can be explained by immigration. This indirectly will have a large negative impact not only on wages, but also a large number of other benefits.

EMPIRICS:

The empirics on this issue are a little tricky. There is a vast body of research to show immigration has an insignificant impact on wages or maybe even a positive impact. However, this data is largely flawed. The biggest reason why is because when the study is examining migrants going into a specific area, however, when this happens natives in droves flee that region. As Borjas&Edo (2022) states “The native internal migration diffuses the impact of immigration from the affected local labor markets to the national economy. The internal migration response also produces a selection bias if the natives who move are not a random sample of the population” The way to get around this problem is to “follow” the migration patterns of displaced natives. Price et al. (2020) do exactly that. First they found that there was an initial increase in employment and in incomes, but after they accounted for internal migration patterns and looked at individual data (instead of aggregate.) They found there were significant losers and winners, with the losers being people who competed with immigrants and winners who employed immigrants. Essentially they founded immigration redistributed wealth upwards. “With our linked data on individual workers, we are further able to identify the relative "winners" and "losers" of immigration. Younger and lower-skilled workers are "losers" from increases in immigration, experiencing income losses and higher rates of out-migration. In particular, those workers who move away from labor market experiencing increases in immigration appear to fare much worse than those who stay, making them "losers" from increased immigration as well. We argue that this represents a form of displacement, as workers' migration responses by skill level are closely correlated with the occupational distribution of immigrant labor entering the U.S. over this time period.”

Another way of getting around this problem is looking at the specific occupations immigrants go into how wages react instead of the simple spatial approach. Kim&Sakamoto 2013 and found that “This occupational approach avoids the bias that is inherent in the spatial approach due to the endogenous nature of immigrants' decisions about where to reside and the economic opportunities of local areas. In contrast to the spatial approach, our results using the same data but employing the occupational approach yield consistently negative net effects of the proportion immigrant on the wages of native workers during the period from 1994 to 2006.” Nickell&Saleheen (2015) uses this approach when analyzing data from England and also found a net negative result. Merel&Rutledge (2017) when analyzed the construction sector and found much more sizable negative impacts. “We find that a 10 percentage point increase in the share of immigrant workers reduces annual earnings of US-born construction workers by at least 4.1%, with workers in immigrant-prone trades experiencing earnings reductions in excess of 7.2%.” This is incredibly significant due to the fact immigrants make up 39% of construction laborers. (Richwine 2025) With this data, construction laborers are losing several thousands of dollars in their yearly salary due to immigration.

To reiterate, the argument presented is not making just the case that increasing the supply of labor will push down wages. It is specifically claiming that capital with an innate preference of cheap labor, will pick the immigrant over the native. Thus for natives to be able to “compete” they will lower their “asking rate” thereby reducing wages

The Economic Argument Will Become Obsolete:

With all of this being said it is visibly obvious the economic argument will become obsolete. The reason why this is, is because the occupations immigrants are most heavily concentrated in are low skilled and labor dense. It is these sectors that are most at risk for automation. We will no longer be reliant on human labor for many jobs, thus will no longer be reliant on immigrant labor to do jobs. As it was already mentioned immigrants make up about 39% of construction laborers. In 2023 the construction sector employed 8 million people. Meaning 3.1 million of those people were immigrants. The Midwest Policy Institute estimated that by 2057, 2.7 million construction jobs will be automated, 35% of those being laborers the bulk of what immigrants do. Immigrants make up 23% of painters in metropolitan cities, which has a risk of up to 90% of its sector being automated (according to the MPI study.)

Another big sector for immigrants is agriculture. This sector is seeing huge gains in automation. The substantial point here is two folded, the first being that America’s economy is becoming less and less reliant on human labor, thus the need for immigrant labor is dwindling. It is also noteworthy that there is almost not a single industry that immigrants make up the majority of. Thus the main argument for immigration, that they do low skilled jobs so Americans don’t have to do them is false. Americans still do these jobs, and more Americans will do them if immigrants wouldn’t put downward pressure on their wages.

Housing and Inflation:

Another argument many on the pro-immigration side of the debate like to make is that immigration is a deflationary mechanism. The only way this could actually be the case is if immigration does depress wages and that has spillover impacts on pricing. However, the pro-immigration wants to argue immigration does not lower wages. It can not be the case immigration has no impact on wages and also lowers prices. It is also unlikely high wages are causing prices to be elevated, as we saw with minimum wage study cited above, a large artificial increase of wages had a small unnoticed impact on pricing. The EPI produced data from 1989-2019 and found labor costs can not explain the increase of inflation, and the two were uncorrelated with each other. If a wage price spiral isn’t happening, and hasn’t happened for a long time, it’s doubtful immigration depressing wages will have an impact on the cost of living. Mind you, this is something the pro-immigration side does not even want to concede.

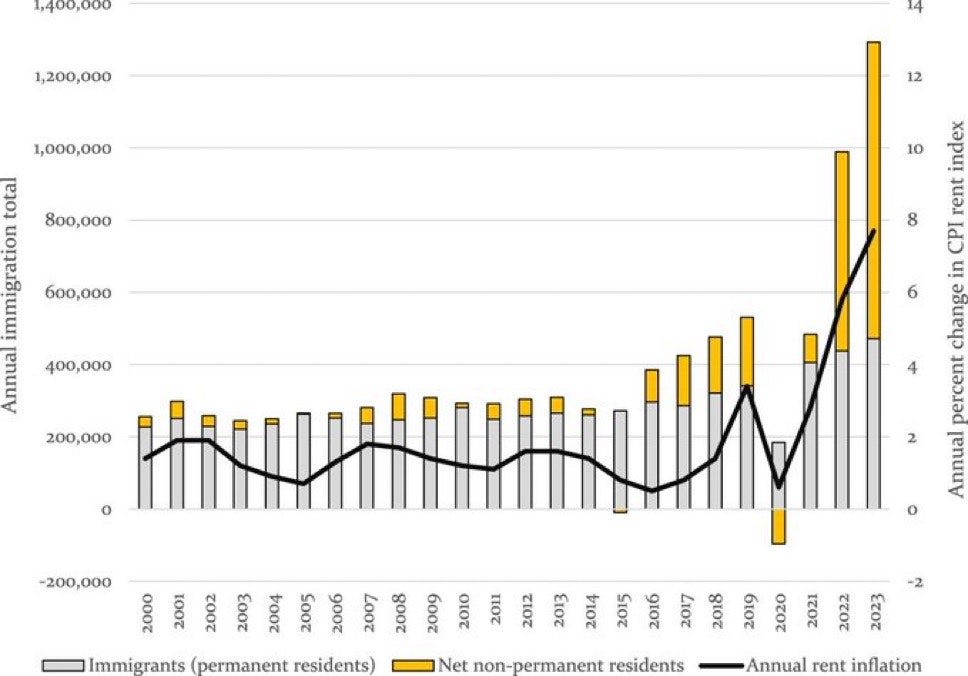

One of the biggest contributors to the rise of the cost of living is housing. Immigration puts upward pressure on housing, and the very dense living situation immigrants live in is bound to increase the cost of housing. Saez (2007) found almost a complete 1:1 ratio between immigration increase to a population and an increase of rent. Guarner (2023) when examining data from Spain found a much larger impact. “I find that a one percentage point increase in the immigration rate raises average house sale prices by 3.3%.” Data from Canada shows immigration might be the driving factor for its recent explosion in housing prices.

One might reply with “why shouldn't we just build more houses.” I agree. We should. However the increase of house construction will not be able to slow down the increase of rents and house prices as those will also be met with new immigrants. Likewise, as Louie et al. (2025) state “The standard view of housing markets holds that the flexibility of local housing supply-shaped by factors like geography and regulation-strongly affects the response of house prices, house quantities and population to rising housing demand. However, from 2000 to 2020, we find that higher income growth predicts the same growth in house prices, housing quantity, and population regardless of a city's estimated housing supply elasticity.” Supply constraints and building more homes is not the driver of the housing crisis, although it might play a role. An undeniable aspect of the housing crisis is the increase of population and competition for housing.

GDP Per Capita

Finally as we have seen in recent years, immigration of non-Westerners into Western countries is associated with lowering of GDP per capita (r = -.41) and the more non-Western immigrants are going to come to the West, the more the West’s living standards would shrink.

This is primary to do with the fact that different ethnic groups have different net impacst, and so groups with lower average IQs in a high IQ nation are going to destroy its living standards by dragging the average population to their common level. Which is…. common sense?

Conclusion:

The center framework of the immigration debate is highly skewed towards orthodox economic consensus. There are several flaws with the orthodoxy and thus with the mainstream immigration discourse. Turning to a much more sound position, that of heterodoxy, we can find a significantly stronger argument against immigration. Likewise, the immigration debate is extremely shortsighted, as it does not take into account millions of jobs immigrants come here to do that will soon be displaced in our lifetime. The drawbacks of this could very much be sharp increases in homelessness and poverty. It should also be of note leftists who engage in the argumentation this article is responding to are in complete contradiction. One can not argue for supply side economics in regards to immigration, but not for other economic policies. This leaves the door open for leftists to accept austerity and other anti-worker policies.

Even though this article is rebutting economic arguments for immigration, and making the case against it. The vocal point against immigration should not be concerned with economics. Immigration is a sociocultural issue that is dramatically changing our society in ways the economy can not measure. Focusing on the economy completely misses the point of what the restrictionist is arguing.

The last point that must be raised is that immigrants are not a homogenous blob that can be shaped into anything we want. As Garett Jones demonstrates in his book, assimilation is a myth because immigrants behave more similarly to their country of origin than their host country, even when controlling for second and third generation immigrants. It matters when immigration is coming from. White immigrants are good. Non-White immigrants are bad. It is really that simple.

Israel is not going to let in Indian immigrants despite many of them being Elite Human Capital and neither should we. In the political debates about porn, no one mentions how we could potentially lose a trillion dollar industry. The psychological wellbeing of our country is vastly more important. It is the same with immigration, the potential lost of our ancestral homelands and culture is vastly more important than the economic growth that could be achieved through immigration (that as we just learned is not even going to happen).

My additions didn’t make it into the voice reading 🥰🥰🥰🥰