Understanding The Protestant vs Catholic/Orthodox Divide

𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐧 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐝𝐢𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐨𝐭𝐡 𝐂𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐎𝐫𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐝𝐨𝐱 𝐂𝐡𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬

What I am about to say may seem obvious to some, but I believe it is often overlooked by others, which is why I feel compelled to highlight it once more. I am about to reiterate the classic trope by which countries which have historically undergone Protestant selective pressures have turned out to be more individualistic, democratic and autonomous.

While we are generally aware of the Protestant drive towards individuation, personal autonomy and self-expression, in the modern era such differences are minimal if we were to look at opinion polls, yet they were crucially important historically.

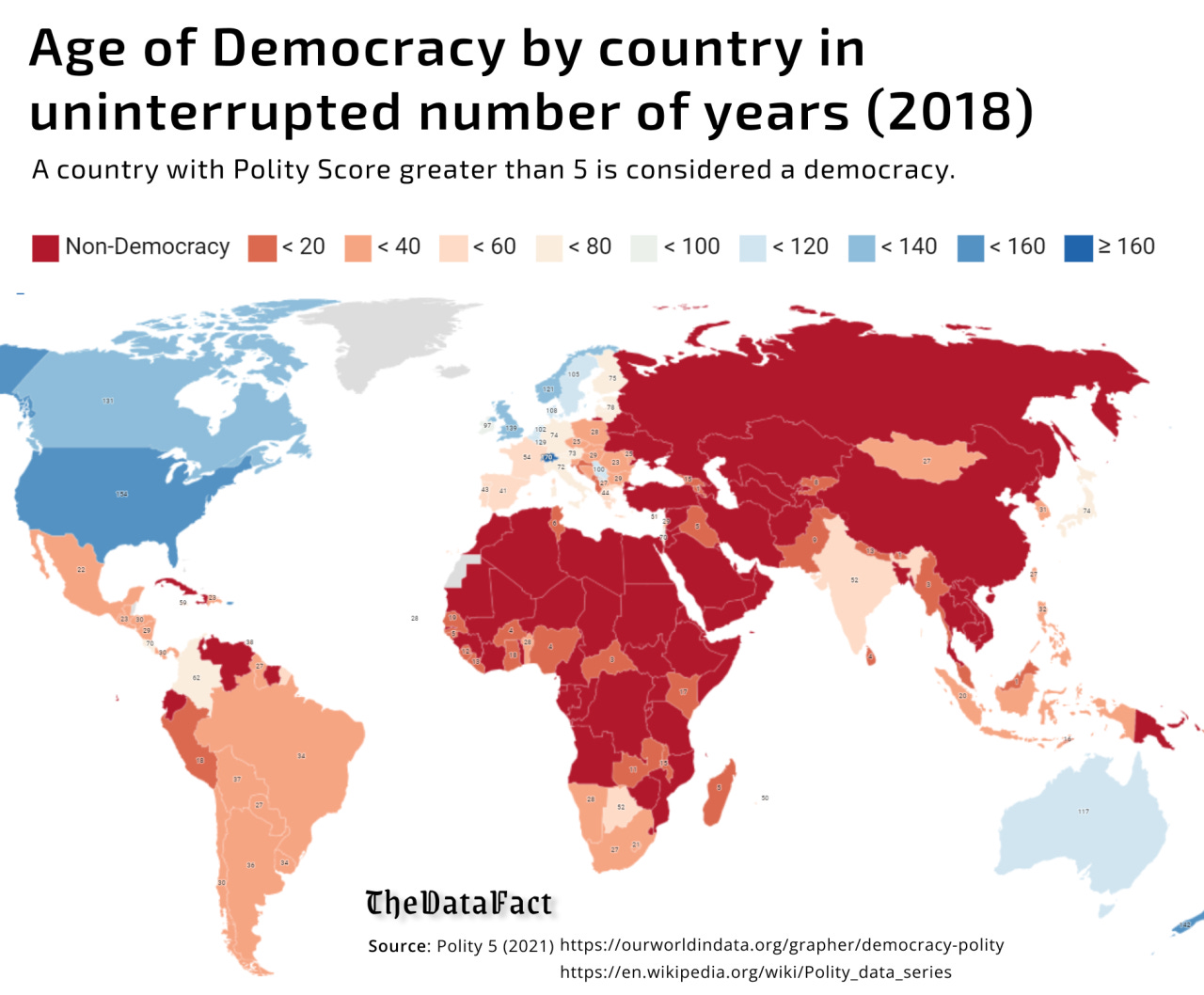

Consider the Dutch Republic and other Protestant democratic formations in Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and of course the United States and the Anglosphere at large. All of the early democracies in the world have been Protestant.

In contrast all of the totalitarian and authoritarian countries in Europe had practically emerged only among Catholic and Orthodox nations. Revolutionary France + Napoleon III, Germany/Austria-Hungary (including Fascist Austria and Nazi Germany), Italian Fascism and the Risorgimento, Czarist Russia, Romanian and Hungarian Fascism, Pilsudskiism, the Spanish and Portuguese dictatorial states and finally the Soviet Union and its satellites.

So not only did Catholics and Protestants failed to adopt a democratic form of government at the same time as their Protestant neighbors, their manifestations and ideas of Democracy and Government have been highly totalitarian as judged by the works of Rousseau, Saint-Simon, Comte, Hegel and Ernst Haeckel to the ideas of Marx, Lenin, Gentile and Dugin.

There is little in the Anglo-tradition that has ever generated these forms of totalitarian thought which primarily specializes in Liberal and Libertarian philosophical thought producing people like Herbert Spencer, Adam Smith and John Stuart Mil.

Protestants emphasized free will, autonomy and small government while Catholics and Orthodox emphasized community, big government and authority.

The result of this is that neither Britain nor the US nor any other majority Protestant country in Europe post the enlightenment had any regime or ideological framework which emphasized the power of the state or authoritarian rule, the necessity of collectivism or the need for revolution over evolution. Catholic and Orthodox nations on the other hand were ruled by authoritarian regimes and contained all the major bloody revolutions of the last couple of centuries within themselves.

German exception?

The German National Socialists are frequently cited as an exception to this trend. However, the party was initially established in southern Germany, predominantly by Catholics, during a period when the predominantly Protestant Weimar Republic functioned as a democratic state, whereas Austria had already embraced fascism.

The reason it appears that Catholics didn’t support the NSDAP that match, boils down to the fact that, they voted for the Zentrum Catholic-Identitarians party instead (same with Bavarian People’s Party). If you were to compare the relative popularity of leftist and democratic parties, you will see that they would be more popular in the Protestant areas of Germany whereas the Nazis and the Catholic Identitarians in Southern Germany.

Why think about this?

Most historians see the main divide in Europe to be formed after the Great Schism in 1054, dividing Europe into its Western and Eastern part, and while it’s important to be aware of it, I think that the biggest political division in Europe (and its oversea enclaves) is actually between Protestants and non-Protestants.

For all their differences, Catholics and the Orthodox are more alike to each other than either is independently with Protestants.

Now, of course, there are multiple Protestant denominations, ranging from Episcopalians to Southern Baptists, they share a common similarity, that which subconsciously values autonomy. For this reason, any form of a totalitarian state are likely doomed to fail in the Anglosphere, whereas Libertarian and similar ideologies can easily take rout in the Anglosphere.

In contrast, the EU which is majority Catholic, is likely to continue heading the direction it’s headed with a popular consent. Perhaps, where these things can be seen more clearly is Canada. While being culturally American, because it is majority Catholic, the political beliefs of Canadians are way more in favor of governmental solutions in relation to Americans. Canadians don’t see any problems with using the government or giving it power, as their ancestors who have outsourced their authority to the Pope and Nobles. Quebec (where the Catholic element is most highly concentrated) is highly reminiscent of a society in which a left-wing French Rassemblement National were to succeed. It is like South America, but prosperous.

Obviously, this dynamic is less relevant today than it was in the past. However, the selective pressures brought about by the Reformation remain observable even now. I am not suggesting that simply converting to Protestantism or Orthodoxy/Catholicism can instill this particular mindset, nor am I claiming that theology holds significant importance in the modern world (it clearly does not). What I am asserting is that the cultures of these nations have been deeply shaped by this historical religious divide.

Because this divide is so embedded in the political culture and DNA, for the sake of being pragmatic, the political Right must adopt a pragmatic approach. It should engage with the existing cultural framework and advance solutions aligned with the nation's historical trajectory. Totalitarianism will never be popular without a demographic transformation occurring in the United States, while Libertarian arguments will always be regarded as the best weapons in the hands of the Right (alongside Biorealism of course), whereas in Russia pro-authoritarian and big-government arguments will most highly resonate with the population.

Because I am mostly focused on the Anglosphere, my Right-Wing Progressivism embodies a non-authoritarian yet intensely right-wing ethos, harkening back to the Puritans, whose descendants spearheaded the Progressive Era of the early 1900s.