The Soviet Union Was Even Worse Than You Imagined

The Soviet Economy Sucked

The following is mostly a translation of a right-wing Russian reply to a popular Russian communist YouTuber Andrey Rudoy.

A treacherous foreign agent, a French villain, Fantomas in a Louis de Funès form factor—anyway, Andrey Rudoy has released a video titled “Why I Hate the USSR.” And he delivered kilotons of base, starting with the fact that killing people for their political views is f***ed up. Now he is trying to gaslight his audience, claiming he always thought this way.

But regardless, it’s a good thing. Discussions with the left—about tax rates, state ownership, taxes on oligarchs, the planned economy, the Soviet legacy, and so on—are permissible and, more than that, productive. We just need to start with a small disclaimer: you cannot kill people for a joke, for failing to hand over grain on time or not joining a collective farm, for the fact that their ancestors arrived in Russia from Bavaria 150 years ago, because their grandfather was a Tsarist general, or for not shoveling snow. And a ruler under whom all the above was the norm is garbage and an a**hole. Yes, “Grandpa Lenin” included.

But after 1953, the Soviet regime stopped killing people left and right, and instead launched a man into space (thankfully, they didn’t kill all the Katyusha designers; Korolev and Glushko survived the camps). And so I decided to try and honestly answer, at least for myself: what do I actually like about the Soviet legacy? Let’s go in order.

Politics and ideology are clear. Zero points there.

Daily life Soviet life I don’t like too. Endless rudeness always and everywhere, the likes of which today’s Zoomers couldn’t even dream of. Hours-long queues. Alcoholism on a scale that, again, would seem unreal to Zoomers. Perpetually filthy toilets. Even the eternal “No Vacancy” sign at any hotel at any time is hard for a Zoomer to imagine.

Disgusting quality of all services. A great stroke of luck was having a “friend” who was a butcher or an auto mechanic. All of this, note, does not directly depend on the standard of living. (Switzerland is one of the richest countries in the world, but the services there aren’t great either; you might wait two weeks for a plumber). It’s not just that Soviet society was very poor—it’s that daily life within it was organized atrociously.

Now for the main part—the economy. Well, it’s impossible to deny the successes of Soviet industrialization, right? We’ll try anyway.

The USSR was solving a problem that dozens (nearly a hundred in total now) of states have solved: the task of modernization—the transition from a traditional agrarian economy (and traditional society) to an industrial one. There is nothing unique about the task itself: everyone solved it, from Victorian England to modern-day Vietnam. What is unique is how poorly the USSR solved it.

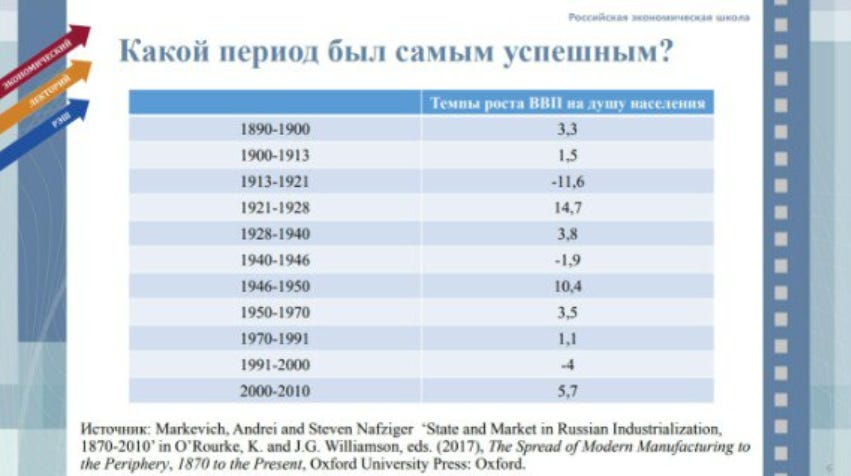

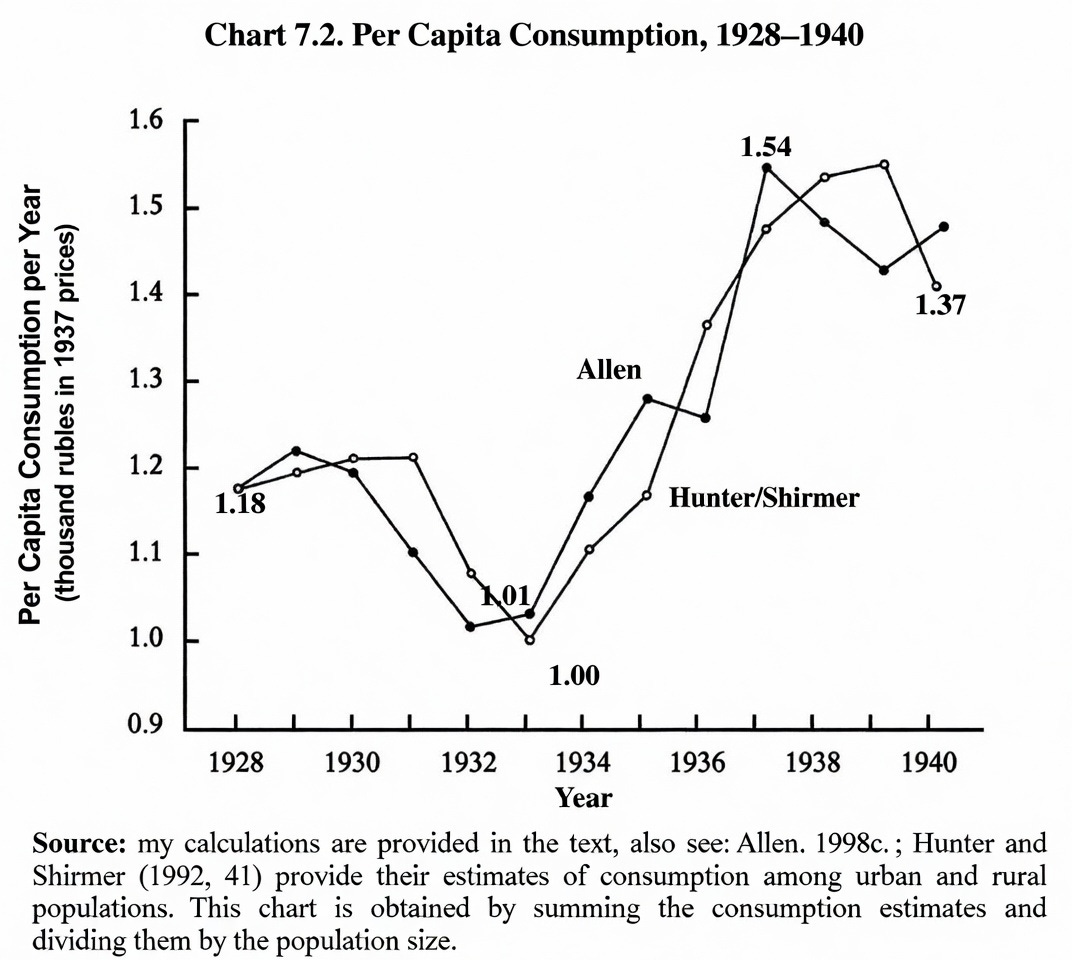

The GDP per capita growth rates in 1928–40 were only 3.8% per year (data from the Maddison Project; also check this out).

[Growth of GDP per capita every decade]

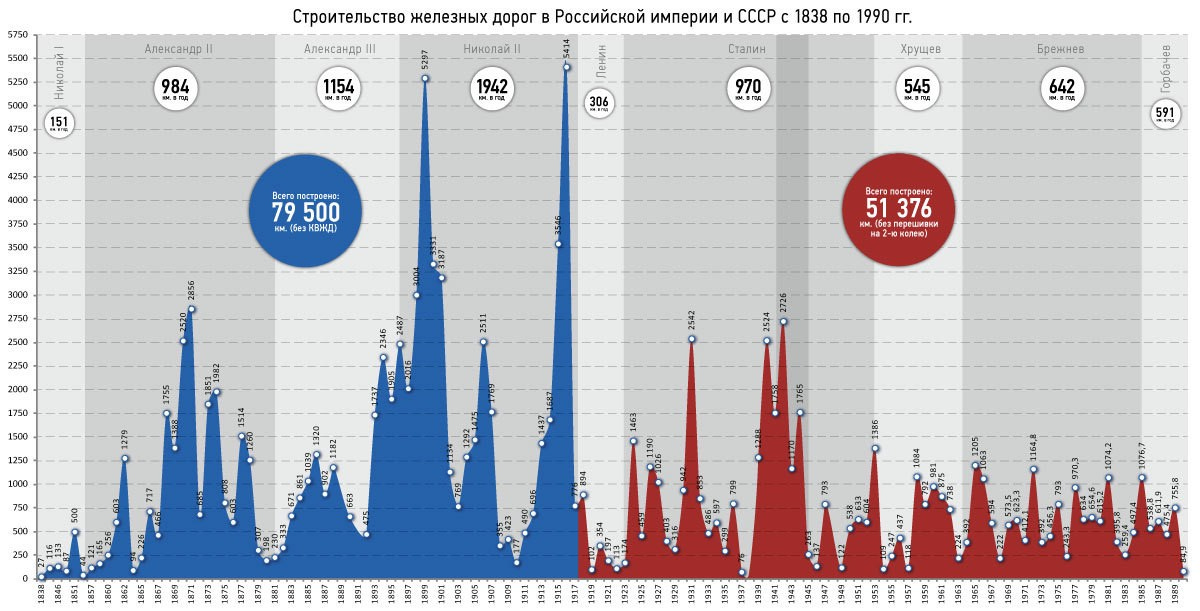

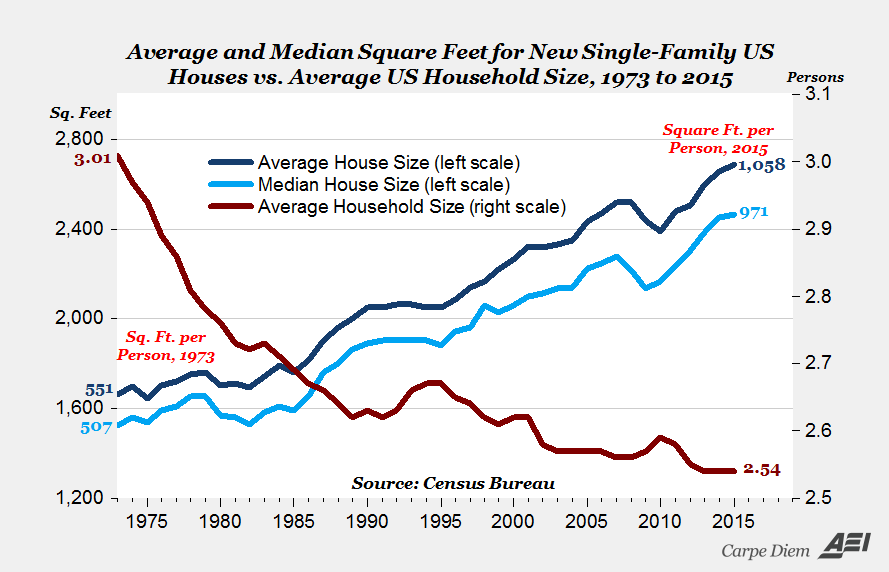

But what about the massive growth in coal mining, pig iron smelting, and the production of cars and tractors—did that not happen? It did. But light industry (in the broad sense) grew much slower than heavy industry (and the latter, even in the broadest sense, made up a relatively small share of GDP). After collectivization, agricultural output collapsed and only barely recovered by the late 1930s. Railroads were built much more slowly than in the Tsarist era. By 1941, there was only one fully paved highway—Moscow-Minsk (which Guderian’s tanks rolled east on). As for small-scale production, like individual tailoring, it didn’t just fail to grow; it was deliberately crushed.

Housing construction, especially in large cities, proceeded at impossibly low rates; Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Kharkov, Sverdlovsk, Novosibirsk, Minsk, and others experienced a horrific housing shortage. On the outskirts of Moscow, entire fields were covered not even by barracks, but by dugouts. A residential “dugout town” immediately appeared on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Savior in the very center of the capital (even before they started building the Palace of Soviets); Woland looks at this town from the balcony of the Pashkov House. In the late thirties, in the barracks of the Moscow “Hammer and Sickle” plant, a leading special steel producer, there was 1.6 square meters of living space per worker; in dormitories, 2.5 sq m. And this was one of the most advanced productions in the country.

Even in 1950, after the start of mass housing construction, only 27 million sq m would be commissioned in cities; in 1960, already 73 million (excluding housing built by collective farms and MTS). It wasn’t about the “struggle against architectural excesses”—even under Stalin, very few luxury houses were built—it was that Khrushchev finally began spending minimally adequate resources on housing.

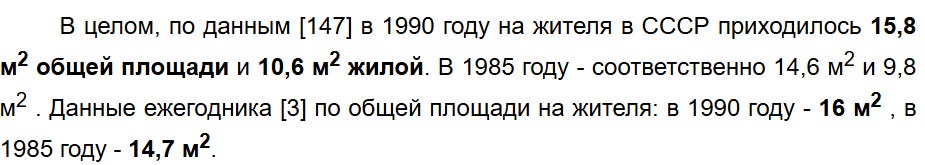

According to data, in 1990 a Soviet citizen had about 10.6 square meters of living space per capita or 15.8 if you include non-living space.

In contrast, in the United States there are 70-90 square meters per person (depending on the calculation). Modern Russian data puts the average square meters per-person at 29 and it is projected to increase to 38sqm by 2036.

Here is a growth of Soviet GDP by various sections of the economy:

Note that this shows the growth of total, not per capita, GDP. It works out to 4.9% per year.

Now let’s put 3.8% per year into context. In 1890–1900, the rate was 3.3% per year. Roughly the same growth occurred in 1908–13, after the end of the war and revolution (note that in the latter case, growth occurred simultaneously with huge expenditures on modernizing the army and navy—just like in the 1930s in the USSR).

But let’s look at the world. Is 3.8% per capita a lot? Korea from 1961 to 1997 maintained a fantastic GDP growth rate of 7.6% per year. (Obviously, maintaining high growth for 36 years is much harder than for 12). China maintained an average annual rate of 6% from 1981 to 2021 (specifically in the 2000s it was also 7.6%). What a comparison, you might say! Those are the super-leaders of economic growth. Okay, here’s Brazil—a country few associate with an economic miracle: in the seventies, growth also reached 6%. Indonesia in those same years—almost 5%. I am specifically citing large countries, but examples could go on for a long time—I just don’t want to turn the post into “insomnia, Homer, taut sails, and the list of ships to the middle.” You can play with the data yourself.

But maybe 3.8% per capita growth was a unique result specifically for the thirties, when the Great Depression raged worldwide? No. In those same years, 1928–1940, Turkey’s growth was exactly the same—3.8%.

Well, it’s clear: Western capitalists are treacherously downplaying Comrade Stalin’s great achievements. On the internet, you can easily find Stalinist tales about growth in 1929–55 at 13.8% per year. The poor fools weren’t taught about compound interest in school, and they preach, without realizing it, about a thirty-fold growth in a quarter-century. (Which is nearly a million times in a century! Behold, the path to the techno-singularity). Indeed, there are estimates that bring per capita GDP growth in the first five-year plans up to 5% (the maximum among estimates worthy of attention). Even such a figure is completely unimpressive.

What is impressive is what accompanied these modest 3.8%. The number of famine victims in the early thirties is estimated by various researchers at between 2 and 9 million people. Our own beloved State Duma in 2008 gave an estimate of 7 million in its statement. In any case, these are horrific losses. The famine was not the result of Stalin’s cunning plan to destroy the peasantry. It was the result of transcendently inadequate plans, multiplied by the horrific cruelty and inflexibility of Stalin’s administrative apparatus. The standard of living, already low during the NEP, plummeted in the early thirties.

The GULAG became a mighty tool for mobilizing slave labor. The role of the prisoners shouldn’t be exaggerated—in the scale of the entire economy, there weren’t that many—but they could be used almost for free (just feed them somehow) for jobs that ordinary workers would only agree to for huge money (relative to income levels at the time).

All of this was an integral part of the Soviet model of “primary” industrialization; otherwise, it simply didn’t work. Again, dozens of countries solved a similar problem—without mass famine, without slave labor, and without lowering the standard of living (strictly the opposite).

Still, let’s agree: if we forget the costs, rapid industrial growth in a world raging with a global crisis—that counts as an achievement. But we must not forget the costs.

What came after? Having recovered fairly quickly after the war, the Soviet economy grew in the 50s and 60s at 3.5% (per capita GDP, again). Japan, the country of the model “economic miracle,” soared far beyond 8% in the sixties. In the seventies and eighties, growth dropped to 1–1.5%.

You likely don’t associate Greece with an economic miracle. But in 1950, Greek per capita GDP was half that of the Soviet Union, and by 1985, it was 30% higher.

Again, even if you add one percent to this growth, you get very sad results (no basis for such “adding” exists, by the way). But even for this growth, a bunch of disclaimers are needed. In the fifties, the development of Tatarstan oil began; in the sixties, Samotlor; in the seventies, oil prices rose (in real terms) about six times; in 1984, large-scale gas exports to Europe began. Let’s agree: the Soviet government’s merit in finding many resources in the vast Russian expanses is small. We don’t praise the sheikhs for the Persian Gulf having a lot of oil.

The USSR exported a relatively small share of its oil to the West, but this oil provided precious hard currency that could be spent on modern equipment and Canadian wheat. The USSR could offer Western countries practically nothing besides resources: almost all manufacturing products (non-military) were of such quality that Western companies didn’t want them for free.

Yaremenko, director of the Institute of Economic Forecasting, recalled that imported excavators accounted for 10–15% of the fleet in the USSR, yet they performed 60–70% of all work. (“Economic Conversations,” fifth conversation). But an excavator is not a CNC machine or a photolithography machine.

But something else is more important. The Soviet economy was transcendently resource-intensive. Several times more natural resources were spent per unit of national income than in the US—a country also very rich in resources and never a world leader in energy efficiency. At the same time, the share of investment (capital investment, what isn’t consumed but goes toward future growth) by the early eighties reached, by estimates, about 38% of GDP. This is far from the limit—the Chinese in the 2000s exceeded 50%—but they had corresponding results.

Billions of tons of valuable natural resources—metals, oil, coal, timber—were spent just on development programs. The Soviet Union, being a mid-developed country (ceteris paribus, the lower the development base, the faster the growth), spent insane amounts of resources on development—and barely crawled forward.

Shlykov writes that, by some estimates, Soviet metallurgy devoured more investment than the entire military-industrial complex. With all due respect to Shlykov, it would be cool if he gave at least some links.

William Easterly (I recommend his “The Elusive Quest for Growth,” by the way) wrote a famous paper showing that TFP growth—roughly speaking, the quality of using physical and human capital—in the USSR was the worst in the world (among countries for which there is relatively reliable statistics).

The Soviet economy was so resource-intensive that in many cases you could close an enterprise or a collective farm, put all workers on welfare equal to their salary, sell the resources used (in the case of a collective farm—fuel, fertilizers, metal for machinery) to the West for currency, and still stay in green. The fact that this economy survived a severe transformational slump in 1991–98 with an average annual growth of -4% is an indisputable and unquestionable economic miracle (with a minus sign), which had many causes, but the main one was Gorbachev’s fantastically incompetent economic reforms.

I highly recommend reading the interviews conducted by sociologist Belanovsky in the eighties.

If Biba cut off one of his arms and Boba cut off both, and Biba feels better than Boba, it doesn’t mean you should cut off one arm. You can cut off nothing and live happily. The catastrophe of the 90s doesn’t make the Soviet economy better or more efficient—on the contrary, it shows how difficult it is to come up with a good exit strategy from this horror. ... I want to talk separately about one graph. If you read Robert Allen’s famous book “Farm to Factory” (it was mentioned several times above, and I wrote a whole article about it), you might remember one graph there. Here it is—drawn a bit prettier than in the book itself, but the data is the same.

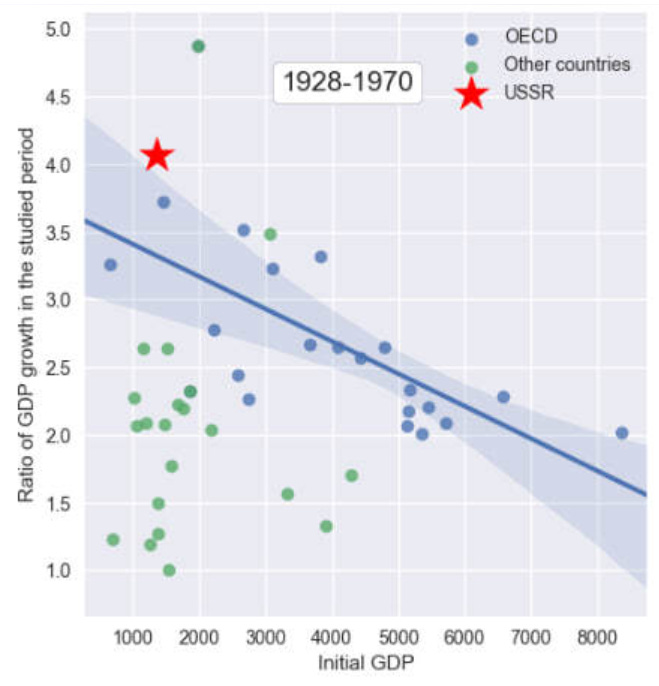

This graph became popular far beyond Allen’s circle of readers. What’s on it? On the horizontal axis—the initial level of GDP per capita in different countries. On the vertical axis—the growth rates in these countries for 1928–1970. The USSR is in second place in the world after Japan (the green dot at the very top). Impressive?

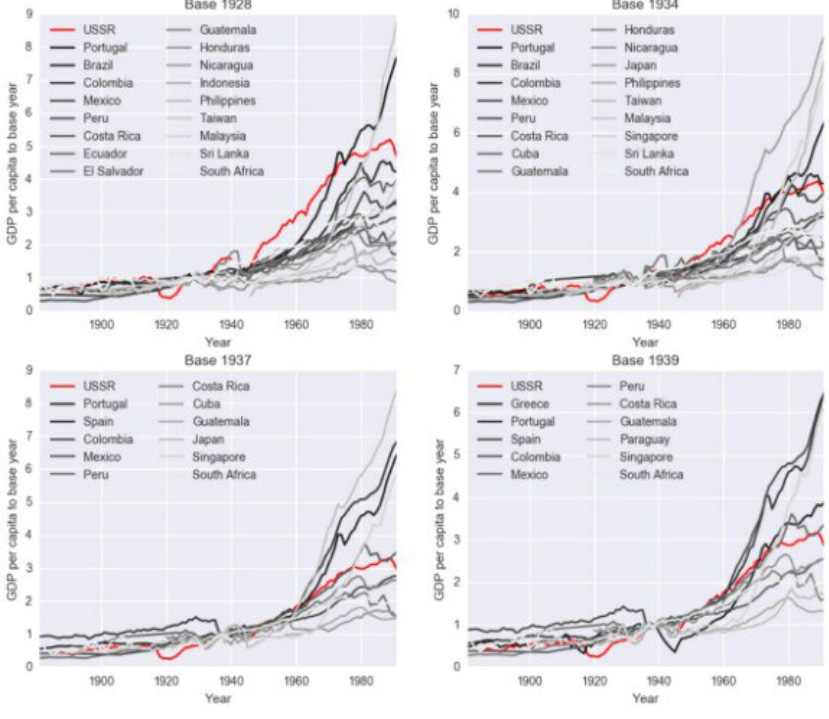

A wonderful article is dedicated to analyzing this one graph. If you’re too lazy to read—you can limit yourself to the graphs below.

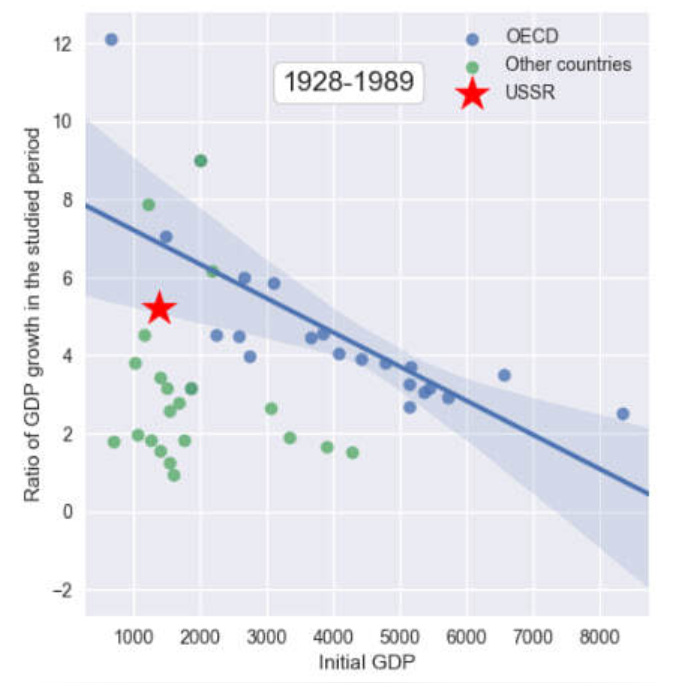

First, everything depends on the choice of period. Change the end point.

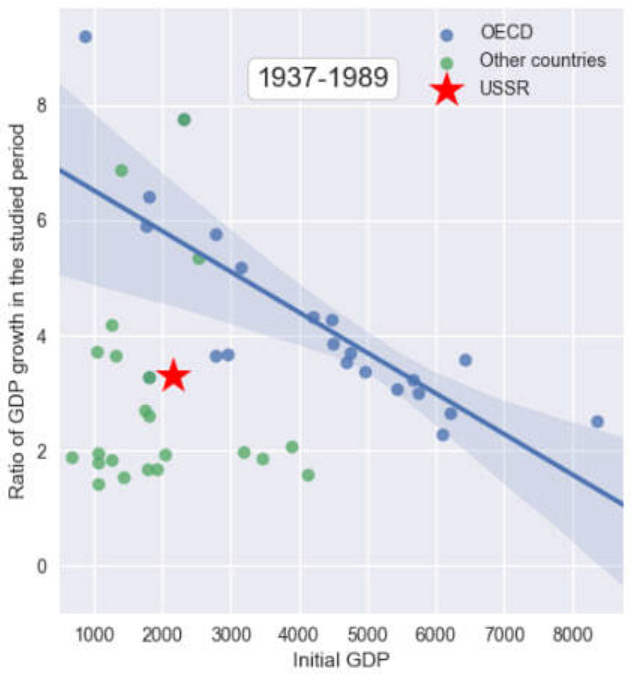

Now change both the starting and end points.

And here is what happens if you look at the dynamics? There are many lines, but we need the bright red one.

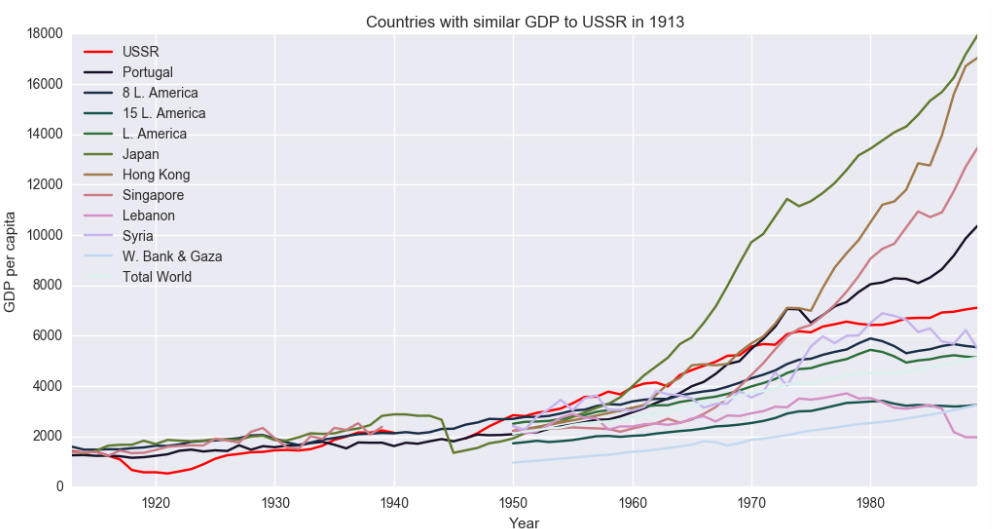

Now we take countries where the per capita GDP was roughly equal to the imperial per capita GDP in 1913 (not sure Syria and Palestine are relevant here, but anyway). Look at the result.

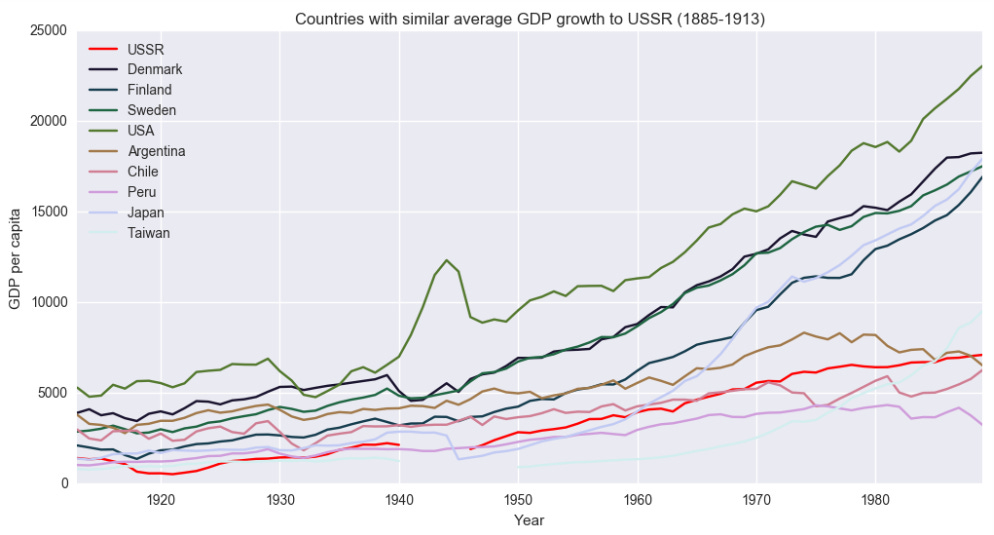

And now we take the leader countries in per capita GDP growth in 1885–1913, which included the Empire. And here everything is quite sad. Finland and Japan succeeded. And for the sake of fairness, Argentina’s was even worse.

By skillfully manipulating statistics, you can “prove” directly opposite theses on the same set of data.

....

Let’s talk about education. We won’t touch the humanities—in the house of a hanged man, one doesn’t talk about rope. But technical education, according to Rudoy, was the “best in the world.” I have several reasons to doubt this.

First, it seems it was considered the best in the world only in the USSR itself. Well, okay.

Second. Income levels in education by 1980 were 63% of income levels in industry—not in some privileged branch, but in all industry, which accounted for close to half of those employed in the economy (tap, and tap). A rural teacher earning far less than a milkmaid and five to ten times less than a “shabashnik” (seasonal worker) who came for the summer to build cowsheds and pigsties (yes, they paid very well on rural construction sites), or a provincial university professor earning half as much as a high-grade milling machine operator—was a common story. It was even worse with equipment. To imagine an engineering faculty somewhere in a region with modern computers is impossible. They weren’t in Moscow universities either, and if they were—who would let an ordinary student near them.

Third, Soviet universities overproduced engineering and technical personnel in giant quantities (just as they would later overproduce “lawyers” and “economists,” in quotes). Engineers were transferred on masse to blue-collar jobs because workers earned much more. There is a 1983 Soviet production film “The Understudy Begins Work” where this is one of the main themes (not worth watching, boring, I don’t know why I watched it myself).

Finally, fourth. In 1992, the average monthly salary in the country was much less than a thousand rubles, the average dollar exchange rate on the exchange was one hundred rubles. Of course, it wasn’t like that throughout the nineties—it’s just that in 1992 the economy hadn’t had time to adjust to free currency exchange—but still, salaries in the country were laughable if converted to dollars. That’s when Western companies should have pounced on specialists with the best education in the world, starting to buy them up by the hundreds of thousands. It wasn’t even necessary to take the engineers anywhere—you could build an engineering center in the country itself. Boeing did in 1993. Soviet aircraft and rocket building was an “elite” industry. Hundreds of thousands of engineers designed and made planes and rockets in the USSR; at the peak, about a thousand worked in Boeing’s Moscow center. I am not aware of any other engineering center of a large Western company of similar scale.

You might say the language barrier interfered—Soviet engineers didn’t know English. That’s where the conversation about the best education in the world can end. Naturally, it’s impossible to get the “best in the world” education and not have the purely technical ability to find out what is happening in your field of knowledge in the world. About half of R&D spending in the 80s and 70s was in English-speaking countries. But it’s not just about the English-speaking countries themselves. I think today you would find it hard to find a Samsung, TSMC, Philips, Trumpf, or Airbus engineer who doesn’t know English (at least at a level that allows reading documents in their specialty). More than that: a person who received the “best in the world” education would, of course, learn a foreign language in a very short time without difficulty if life pressured them.

In the USSR, there was indeed a group of specialists who left for the US on mass, a group that was indeed hunted—not by companies, but by leading universities. These are theoretical physicists and “pure” mathematicians. They left by almost entire departments, entire sections of research institutes.

They say American theoretical physicists have a joke: if you have a good idea, it means half a century ago a paper was already written in Moscow based on that idea. A friend of a friend told me how in Amsterdam he accidentally started talking in a bar with an old man who spoke very good Russian. It turned out the old man was a quantum physicist, and it was simply impossible to do quantum theory in the sixties without the Russian language. So he learned it, what else could he do.

The fact that the USSR—a relatively poor country—turned out to be one of the two world leaders in the most fundamental sciences (mathematics and theoretical physics) seems very appealing to me personally. Yes, it wasn’t the original plan of the Soviet leadership, but just one of the side results of the nuclear project. Yes, young people went to study at the FOPF and the physics faculty of MSU/LSU, at the mechanics and mathematics faculties of the same universities not only out of love for science, but also because this education was a powerful social elevator and a direct path to a comfortable life with interesting work.

(Physicists, especially in the defense industry, often earned huge money and were provided for at the level of the party elite—like major aircraft engineers, for example. We don’t know the exact scale of rewards for “military” scientists. Unfortunately, the materials of the “Kremlin Seven,” the Military-Industrial Commission that sat in the Senate Palace—the one depicted on all Soviet banknotes—are still classified. The very fact of the existence of this powerful organization, which united seven “defense” ministries, became known to the public only in the 2000s).

But the fact remains: in the USSR, a poor, unsettled, poorly managed, ideologized, criminalized country—in the USSR there existed a powerful fundamental science, even if only in a couple of areas (in biochemistry or pharmacology, the USSR’s positions were, of course, incomparable with its positions in mathematics and physics). To me, this adds a little faith in humanity.

Another appealing feature of the Soviet past (quite well-preserved in the present) is the physics and mathematics schools. The fact that we are not doing too badly with mathematical education today is proven, for example, by the results of international olympiads (both school and student—in programming, for example). And not only in phys-math schools, but in schools in general—the TIMSS results are proof of that.

Phys-maths appeared largely by accident. In the late 50s, the military, or rather, scientists in uniform with big stars, demanded the creation of mathematical schools—they needed young people who in the future would be able to operate complex computers. The military was supported by academics—Semenov, Sakharov, Kolmogorov, and others. A letter to the Central Committee from four “defense” ministers—defense, aviation, radio, and electronic industry—was of key importance. For the Soviet authorities, phys-math schools were always an “alien element.” In Leningrad in the seventies, local authorities suppressed them with all their might: Sergei Rukshin, who worked as a teacher at School 239 then, recalls how a commission of 25 freeloading bosses would barge into his lessons. Phys-math schools were required to accept students not by competition, but by territorial principle (which, naturally, killed the very idea of such schools). Nevertheless, FMSH have survived to this day, and it seems to me that school education with an emphasis on mathematics is very cool and correct.

It’s not just that people who know mathematics well will always be needed. It’s also that mathematics simply clears the brain perfectly.

The main Russian conservative publicist in the 70s and 80s of the XIX century was Mikhail Katkov. He was simultaneously a conservative and a Westernizer—in particular, a supporter of transferring classical European gymnasium education to Russia, with an emphasis on Latin and mathematics. The Jesuits were the first to think of making such an emphasis. The idea here is as follows. It’s pointless to try to prepare a ready specialist right at school: a child doesn’t yet know what they want to do, and anyway—that’s not the task of the school. The task of the school is to accustom a small person to constant hard intellectual labor and, importantly, to accustom them not just to memorizing random bits of information, but to persistently, year after year, analyze the structure of a complex system.

Mathematics as an academic discipline has many interesting properties, but I will point out only one. A huge advantage of mathematics is that it shows everyone who practices it the limitations of their abilities. You try to solve a problem, nothing works, and at the end a solution comes—or you just read the solution in the answer key. And you are amazed at how simple everything is and how stupid you are if you couldn’t figure it out yourself. This... is refreshing.

In general, phys-math schools and the emphasis on mathematics in school education as a whole is another inherited feature from the USSR that seems positive to me. I may be wrong; correct me if so.

...

There is also medicine. Not my topic, I won’t write much, just a few strokes.

Rusecon sent me his forthcoming article about the state of medicine not somewhere in the backwoods, but in the hero-city of Leningrad, the cradle of three revolutions, in the 70s–80s. There is much that is impressive there, but one thing especially. In a children’s hospital, there has been no hot water for four months, and the ceiling in one of the departments has collapsed. Repairs are planned for two years from now. This is from official inspection materials.

In the seventies, infant mortality began to grow in the RSFSR (!)—though not by much. In 1980, infant mortality was 2.21%. Do you know how much it is in 2024? 0.4%. You might think this is thanks to new medicines; but Japan reached roughly the same figure back in the 1980s. It’s not about miracle drugs, but about the catastrophic underfunding of obstetric care in the Soviet system.

The first successful heart transplant in history was performed by South African Christiaan Barnard in 1967. (Three days later, the first transplant was already done in the US, and a month later—the first successful one). Barnard considered Vladimir Demikhov his teacher, and he specifically went to his laboratory to learn from his experience. Do you know when the first successful heart transplant was performed in the USSR? In 1987. The numbers 6 and 8 look so similar, don’t they.

...

Having dealt with serious things, let’s talk about the subjective—culture. First, literature. Personally (tastes differ), I like many writers and poets from the USSR. Bulgakov, Rubtsov, Shukshin, Astafiev, Shalamov, even Brodsky or Zoshchenko. As is easy to notice, all of them at best existed parallel to mainstream Soviet culture. Well, okay, “And Quiet Flows the Don” and some of Simonov’s poems are also good, but that’s not much. The “core” of Soviet literature is Ostrovsky’s “How the Steel Was Tempered” and other indescribable crap. It’s hard for me to imagine a person who today would be interested in “production dramas” by venerable proletarian masters of the pen whose names no one remembers.

Architecture? Personally, I am indifferent to constructivism, and Brezhnev’s brutalism is some kind of junk. Stalinist Empire style is generally boring and monotonous. True, the Stalinist skyscrapers are indeed beautiful, although building them in a starving country ruined by war was a crime. The MSU building is magnificent, but you have to understand that even today such a building would be transcendently expensive. Glass-box skyscrapers are built not because everyone loves “glass and concrete,” but because it’s cheaper.

And in general, the best example of Soviet architecture is, of course, the New Arbat. Khrushchev went to Cuba and really liked the luxurious tall hotels built along the embankment. He wanted Moscow to have the same. The phantasmagoric absurdity of Posokhin’s “books,” moved from the tropics to the center of a huge northern city, is a good metaphor for the entire Soviet project.

Movies? I’m not going to act like a snob and say I’m indifferent to Soviet films. I love the comedies of Gaidai, Danelia, Ryazanov, and the series about Stierlitz, and “Nine Days of One Year,” and “Office Romance,” I like watching Mironov or Mikhalkov on the screen. Terribly enough, there is even a production drama that I like—”The Bonus” with Leonov in the main role. You can’t say that good movies aren’t made at all today—but very few are made, certainly fewer than then. So, do we agree with BadComedian?

First, we know dozens of good Soviet films—and we don’t know thousands of bad ones. Open a Wikipedia article “List of Soviet feature films (19xx)”—pick any year—and count how many of these films you’ve watched. Since Grandpa Lenin decided that the most important of the arts for the Bolsheviks is cinema (without any circus!), then a lot of money was spent on cinema. If you shoot a lot—some part will inevitably be good.

This is the highest-grossing film in the history of the USSR. Have you seen it?

Second, outside the USSR, Soviet films were almost not watched. Mosfilm never had a chance to become Hollywood. Cinema collapsed in the nineties not only because state funding ended, but also because everyone got the opportunity to watch whatever they wanted. And they wanted to watch the Terminator and the Titanic.

And finally, the Stanislavski method and Russian theater in general were not invented by commissars in dusty helmets.

....

I don’t want you to think for a moment that I represent the late USSR as hell on earth. Life then differed from life now much less than from the terrible meat grinder of the thirties. But I honestly don’t see anything valuable in the Soviet past, except for such a small detail as the emphasis on mathematics in education (well, and a few good movies that can be rewatched).

In general, comrade Communists, who for some reason decide to read this text: let’s agree with you on two points. First, you cannot kill people you don’t like. Second, you need to grind mathematics (coding, physics, even—perish the thought—economics, just not political economy, but normal, at least the linear programming you love). You can, if you must, grind for the glory of communism.

…

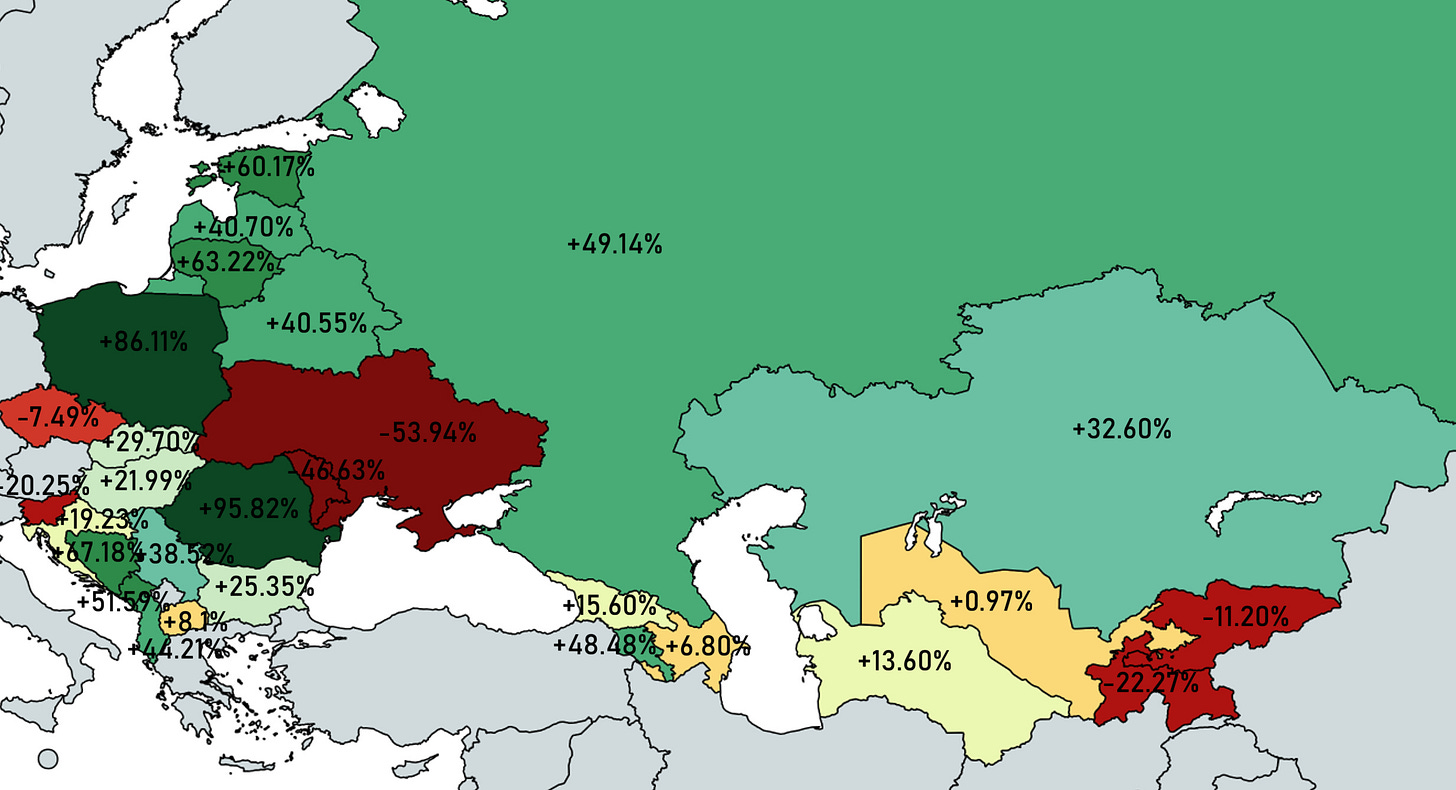

In my own substack post dedicated to measuring GDP change relative to the world’s average after the collapse of the Soviet Union, I have calculated Russia as one of the economic winners from the collapse of the USSR.

My next post is going to be about Nick Fuentes and it will also turn into a video.